The Exegete and the Historian

From the invasion of Gaul to the Metaverse

[Continued]

IV

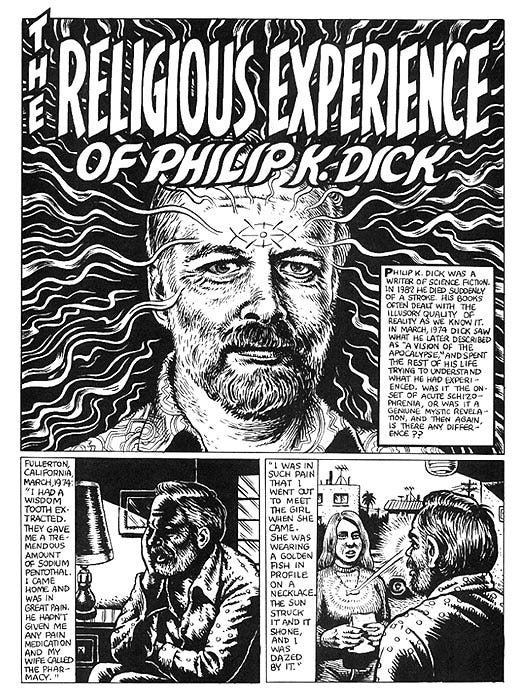

I am not a historian. I am an exegete.

And I am an exegete because I believe in The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick.

I take seriously what he experienced, what he wrote, and what he lived—just as I take seriously the visions of poets and seers Villon, Rabelais, Rousseau, Blake, Tolstoy, Nerval, Rim, Jarry, and Artaud—all of whom will accompany us on this long path of the Sans Rois.

The “Sans Rois” are the spiritual descendants of the Gnostic Christians—those whom the Church labeled heretics or Manicheans

They are the Christians who, starting with Simon the Magician, chose to follow Jesus’s words rather than reconstruct the authoritarian and hierarchical religion he had come to abolish. A religion of commands and prohibitions. A religion of Power.

They are those who fought against Power without ever trying to seize it.

The most famous were the Good Men, also called Cathars.

They were exterminated by the Church.

Though their metaphysical doctrines differ, what unites them is the belief in two gods:

A false god, insane, cruel, blind, and stupid, who thinks he is the master of humanity.

A true God, revealed by Jesus, who is powerless in this world but acts through the heart of human beings.

The false god is the Demiurge, a kind of super-Caesar.

It is him whom Rimbaud mocks in Le Mal (1870):

“There’s a God who laughs on damasks of altars, incense,

Golden vases; who dozes under the hosanna’s drone,

And wakes when mothers, black with grief,

Place pennies in his crude donation box.”

Yes—that god.

But there is another—

A true God, who shines through powerlessness.

Whose kingdom is not of this world.

But who touches hearts that love justice.

Alfred Jarry, in La Revue Blanche in 1899, summarized this duality well:

“Christ did not come to fulfill the old law of Jehovah—the law of the Demiurge—but to abolish it.

All religions adore the Demiurge.

Gnosticism adores God.”

V

What follows is the beginning of a journey.

A journey I hope to continue over several years and several books, whose purpose is to traverse, question, and recount an alternative narrative to the national myth—

From Caesar to Macron,

From the invasion of Gaul to the Metaverse.

“We are a people of refractory Gauls,” said the little president Macron.

“You are ‘Sans Rois’,” says Jesus in the texts found at Nag Hammadi.

It is now up to us to write our non-Roman history.

Our non-lordly theology of History.

What follows is an exegesis of the history of our life on this territory we’ve gotten used to calling France.

A history of our struggle—both spiritual and material—against all forms of political and religious power.

A history of our quest for emancipation,

Of our battles,

Of our defeats,

Of our returns,

Of the times we got back up again.

So, as the saying goes:

If you don’t like my History of France—write your own.

Postscript

That last sentence is actually a tribute to Damon Lindelof.

“If You Don’t Like My Story, Write Your Own” is the title of the fourth episode of the 2019 Watchmen series, where Lindelof rethinks American history, structural racism, and transhumanist temptation.

That line itself is borrowed from Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian writer who, in Things Fall Apart (1958), explained his desire to reinvest in his people’s pre-colonial past and their colonization by the British at the end of the 19th century:

“If you don’t like someone’s story—write your own.”

L'empire n'a jamais pris fin: Tome 1 : De Jules César à Jeanne d'Arc

French edition | by Pacôme Thiellement | 10 Oct 2024

Paperback and Kindle