The Empire Never Ended

Pacôme Thiellement on Philip K Dick's Exegesis

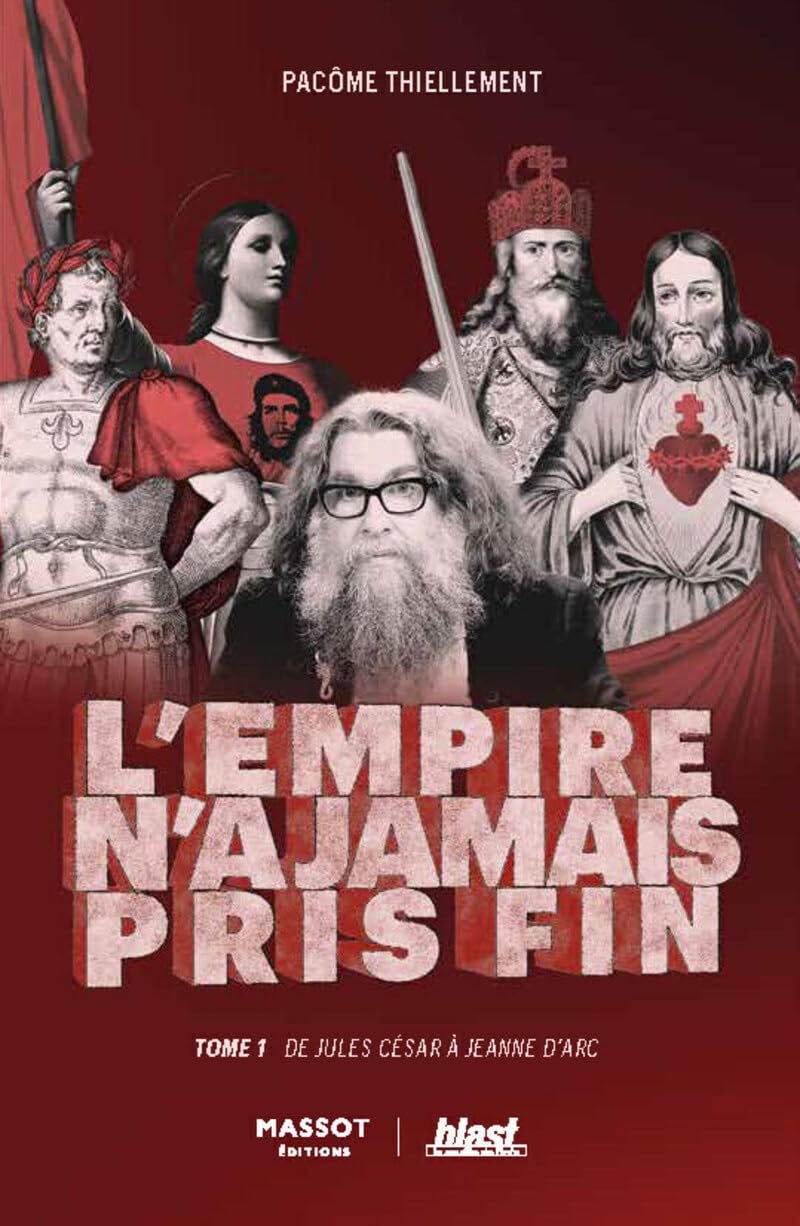

[Thanks to Ben Watson for permission to run his translation of the introduction to Pacôme Thiellement's L'Empire n'a jamais pris fin (Massot éditions, October 2024)]

Introduction — Is it the past? Or the future?

“There are no books on it and no authorities on it. But there it is: Christ against Caesar, the latent inner versus the obvious outer. This is the underlying tale told down through 2,000 years and yet never told at all.”

—Philip K. Dick, The Exegesis p. 401

1

“The Empire never ended.”

This phrase appeared for the first time in a dream of Philip K. Dick’s. In The Exegesis, begun in 1974, we find a short note without a date:

“Dream: store of rare old S-F magazines; I am searching for a serial (novel) called, ‘The Empire never ended.’ It is the most important story of all.” p. 421

In Valis, a novel with strong autobiographical inspiration written in 1978, he elaborated further through his main character (whose name is Horselover Fat, a multilingual play on Philip Dick):

“’The Empire never ended,’ Fat quoted to himself … Originally the sentence had been revealed to him in a great dream. In the dream he again was a child, searching dusty used-book stores for rare old science fiction magazines, especially Astoundings. In this dream he had looked through countless tattered issues, stacks and stacks, for the priceless serial entitled ‘The Empire Never Ended.’ If he could find it and read it he would know everything; that had been the burden of the dream.” pp. 53-54

The story began four years earlier, on February 19, 1974, in Fullerton, California. Philip K. Dick, then 45 years old and who’d already written most of his oeuvre, had just had a wisdom tooth removed. When the pentothal wore off, he called the dentist again, who prescribed a local analgesic that was to be delivered from the nearest pharmacy. The person who brought the medicine is a young woman with black hair, wearing a gold necklace with a pendant in the shape of a fish.

“What’s that?” Dick asked her.

“A symbol used by the first Christians,” the young woman replied.

“At that moment,” Dick would later recount, “when I looked at that shining fish and heard her words, I suddenly experienced what I would later learn is called an anamnesis—a Greek word meaning literally ‘loss of amnesia’. I remembered who I was and where I was. In that instant, in the blink of an eye, everything came back to me. The girl was a secret Christian, just as I was. We had to communicate through cryptic signs.”

For several months, Philip K. Dick experienced an altered state of consciousness. A plunge into a realm of knowledge where he became the host of a voice. The voice of a being he variously called Ubik, Logos, Zebra, Val, or Thomas. Thomas was a disciple of Jesus persecuted in the year 70AD. And it was Thomas who told Dick that everything that had happened over nineteen centuries from 70 to 1974 belonged to the realm of a collective hallucination. In reality, the Empire had never ended. The voice stopped speaking after the resignation of Richard Nixon — an event Dick had anticipated and hoped for. But he would spend the rest of his life analyzing and interpreting what he had experienced.

He did so over nearly eight thousand pages, written almost every night until his death on 2nd March 1982. These thousands of pages form a body of work that he himself titled the Exegesis. We waited a long time before being able to discover the Exegesis, and we still have only a partial edition: a selection of extracts (apparently just a tenth!) compiled by Pamela Jackson and Jonathan Lethem, published in 2011 (and translated into French by Hélène Collon between 2015 and 2016).

In the Exegesis, Dick regularly had the opportunity to clarify what he meant by “the Empire” or “Rome”:

“Rome is a paradigm. They took me to the top of the mountain, so to speak […] to show me something. ‘Do you see?’ the Spirit said to me. ‘What do you see around you?’ What you see is Rome […] One can say that there are two Romes. There is—or there was—the phenomenal Rome, imprinted in linear time and now vanished, like everything else embedded in it. But as an archetype, Platonic Rome still exists, outside (our) time; and it is this Rome that I saw. It is underneath and supports all. It is the seed inside the fruit, what our world really is once you peel away all the deceptive layers of illusion. Only the outer names have been changed.”

What opposes Rome or the Empire? First, it is the liberating word and actions of a man — or a god — who appeared in the 1st century CE, named Jesus. But the Church, which claimed to continue his message, in reality perpetuated the work of Rome:

“The Empire endures. It never ended. Orthodox Christianity is one of the forms the Empire takes.”

Another dream Philip K. Dick had at the time goes even further:

“Dream: all the churches are under the sway of Satanism and derive their power from Satan himself. The Second Coming has occurred—outside the churches; the true church is forming outside the institution […] The churches have mistaken their God; it is Satan they worship. Those who worship the true God have been expelled from the Church. It is not only that the institutional church lacks the true gnosis; no — it worships Satan and derives its considerable power directly from him.”

Philip K. Dick saw the United States of America and the Soviet Union as two contemporary continuations of the Empire. He explained this in Radio Free Albemuth, an early version of Valis written in 1976, abandoned, and published posthumously in 1984:

“The USA and the USSR, I understood, were the two portions of the Empire as divided up by the Emperor Diocletian for purely administrative purposes; at heart, it was a single entity, with a a single value system.” pp. 156-157

“Rome lay spread out everywhere across the ages … Rome weighed down the world, armored as it was, huge with its black iron walls and cells and streets, its chains and rings of metal, its helmeted warriors.” p. 158

They weren’t the only ones. All the peoples Rome colonized also, in their own way, “continued” Rome — if not in deeds, at least in spirit. Especially Gaul, that piece of the planet we’ve become accustomed to calling France.

And it is this piece of the planet that will concern us here.

2

France, the “eldest daughter of the Church,” is logically also the eldest daughter of the Empire. The way in which it was contaminated by the forms of Roman patriotism was already a central concern for philosopher Simone Weil. Her visionary analyses are found in writings that, like Dick’s Exegesis, were published posthumously.

Most notably in The Need for Roots (L’Enracinement), a long text written in London between January and April 1943 and left unfinished when Weil joined Free France. What she tried to develop there was a form of “patriotism subordinate to justice”—that is, to conceive “the reality behind the name France in such a way that, as it is, in its truth, it can be loved with the whole soul.” And that requires sifting through everything in its history that follows the imperial model—where France continued Rome and its cult of grandeur—and how it fought Nazism with very poor weapons.

Already in her 1940 text, “Some Reflections on the Origins of Hitlerism,” Simone Weil stated:

“Only Hitler, in two thousand years, has managed to copy the Romans correctly.”

She examined various French continuations of the Empire. If the French identification with Roman thinking peaked with Richelieu, Louis XIV, or Napoleon, it is nonetheless present everywhere and at all times, in ways more or less harmful:

“France has had many first-rate minds who were neither servants nor worshipers of force,” writes Weil (citing notably François Villon and François Rabelais). “But those who were both have shaped every generation. The only epic poem taught in schools glorifies Charlemagne—that is, a project of universal domination. The cult of grandeur, conceived in the Roman mold, has been handed down to us by an almost unbroken chain of celebrated writers.”

And that’s hardly surprising, given how deeply Rome permeated human consciousness through the writing of history. Rome invented propaganda as the necessary accompaniment to force. And we still see the world through its distorting lens:

“We only know Roman history through the Romans themselves and their Greek subjects—unfortunate people compelled to flatter their masters. It takes continuous critical effort to judge Rome’s politics fairly. We’re used to seeing through Roman eyes, even when it’s Gaul they’re conquering […] Propaganda and force supported one another: force made propaganda almost irresistible by silencing opposition; propaganda spread the reputation of force everywhere.”

Trying to tell our history without falling into the Roman illusion—trying to think our past without adopting a propagandist’s view—is extremely difficult. Doing so through an exegesis of History itself is even riskier. As Simone Weil wrote:

“By the nature of things, documents come from the powerful, the victors. History is thus nothing more than a compilation of depositions made by murderers about their victims and about themselves.”

One can approach this from many possible paths. That’s what I intend to do in The Empire Never Ended. Even as I follow those paths, I’ll strive to be:

Rigorous in the facts. Free in interpretation.

[⮞ Part III–V, conclusion, and full footnotes continue in next message due to length limit.]

You said:

How are you getting on?

ChatGPT said:

All set! Here's the rest of the complete translation of the Introduction to L’Empire n’a jamais pris fin by Pacôme Thiellement—continuing directly from Part III through to the unnumbered conclusion and postscript, with no labels added, and faithful to the original structure and content.

3

I am not a historian. I am an exegete.

So I do not practice History in the scientific sense.

What I propose in The Empire Never Ended is an exegesis of History—that is to say, an interpretation of its text. A “subjective” interpretation, drawing from chronicles, stories, literary references, and mythical constructions.

What interests me are the crumbs of that strange biscuit called the national narrative—that story that still weighs so heavily on our present.

Whether it’s Clovis, Dagobert, Charlemagne, the Albigensian Crusade, the civil war between Armagnacs and Burgundians, or Joan of Arc—the historical text in the book you hold will be interpreted with total freedom.

But it is always interpreted—even (and above all) by those who believe they are being objective. Piling up degrees, citing sources, and playing the academic doesn’t change a thing.

As the great Persian mystic Shihab al-Din Yahya Suhrawardi said:

“Read the Qur’an as if it were written solely for your case.”

And one must add:

No one has ever read the Qur’an other than through their own situation.

And History is read the same way.

Admitting your subjectivity is less a “method” than a matter of honesty.

Jules Michelet said:

“Augustin Thierry called history narration; Guizot called it analysis; I call it resurrection.”

Today, people mock Michelet—too romantic, too lyrical, too out of date.

But they forget how much we’ve been shaped—consciously or not—by his work.

Jules Michelet invented our history.

And his invention has become, in many respects, our reality.

However debatable his interpretations may be to modern historians, his History of France became our Bible, our Qur’an, our Bhagavad-Gītā.

Mocking his errors or flourishes is to forget the power of his gesture. The man entered an immense labyrinth, with countless branches.

And that journey through the labyrinth of History made his solitary undertaking a universal adventure, and his meditation on the past into a writing of the future.

Henry Corbin, the great Islamic scholar, wrote:

“The Book is alive because it continues to ‘happen’ in souls.”

Like the Bible, the Qur’an, or the Bhagavad-Gītā, the History of France is not over.

It is still being written.

In its symbolic dimension, History is still playing out in souls.

That’s why it needs exegesis.

Each time a new one.

Each time a unique one.

Like any sacred text, History has as many faces as there are people reading it as if it were written just for them.

“The past dictates the future,” says Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks: The Return,

just before going back in time to modify the past and understand the present more deeply.

More than ever, the way we read our past in the light of our present determines how we will write the future.

[The second part will be in the next newsletter]