Guy Debord credited the Surrealists for having asserted the ‘sovereignty of desire and surprise’ in their projection of a ‘new way of life’. But he found an ‘error at the root’ in the surrealist idea of the ‘infinite richness of the unconscious imagination’. The ‘techniques’ born of this idea, such as automatic writing, had tended towards tedium and occultism. Furthermore, Surrealism had mistakenly put itself ‘au service’ of a revolution in Russia which had already been lost.

Debord said that the defeat of the social revolutions following the First World War had left the Surrealists and the Dadaists ‘imprisoned in the same artistic field whose decrepitude they had denounced’. ‘Dadaism had tried to repress art without realising it; Surrealism wanted to realise art without suppressing it’. What was necessary, in Debord’s view, was to project suppression and realization as ‘inseparable aspects of a single supersession of art.’

Following the founding conference of the Situationist International in 1957 - attended by modernist artists from mainly Surrealist backgrounds - Debord argued in his Report on the Construction of Situations that 'the problems of cultural creation can now be solved only in conjunction with a new advance in world revolution.' In order to combat the passive consumption he saw defining spectacular culture, Debord called for the international to organize collectively towards utilizing all of the means of revolutionizing everyday life, 'even artistic ones.’

'We need to construct new ambiances that will be both the products and the instruments of new forms of behaviour. To do this, we must from the beginning make practical use of the everyday processes and cultural forms that now exist, while refusing to acknowledge any inherent value they may claim to have... We should not simply refuse modern culture; we must seize it in order to negate it.

No one can claim to be a revolutionary intellectual who does not recognize the cultural revolution we are now facing... What ultimately determines whether or not someone is a bourgeois intellectual is neither his social origin nor his knowledge of a culture (such knowledge may be the basis for a critique of that culture or for some creative work within it), but his role in the production of the historically bourgeois forms of culture. Authors of revolutionary political opinions who find themselves praised by bourgeois literary critics should ask themselves what they’ve done wrong.'

Debord argued that art could no longer be justified as a 'superior activity' or as an honourable 'activity of compensation’. In the new conditions of the culture industry only 'extremist innovation' was 'historically justified'. The 'literary and artistic heritage of humanity' could, however, still be used for 'partisan propaganda' because its artifacts could be deflected or 'détourned' from their 'intended' purposes.

If you want to know what 'détournement' means think back to the portrait of Elizabeth Windsor with a Union Jack flag and with a safety pin in in her nostrils that Malcolm McClaren used to advertise the Sex Pistols' 'God Save the Queen.' The Situationist concept of ‘Unitary Urbanism’ sought to transform existing buildings and whole neighbourhoods into places for play and enjoyment, as opposed to what they have now become: gentrified hubs of alienation imposed by planners and developers, with high-rise atrocities designed by po-mo inspired architects.

In Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967), the first thesis states that in a world in which ‘all that was once directly lived has become representation… the separation from, and disappearance of, life has become perfected’. By 1968, when the streets of the Paris were once again fought over, the city of the Letterists had disappeared and its utopian urbanist potential had already been largely destroyed.

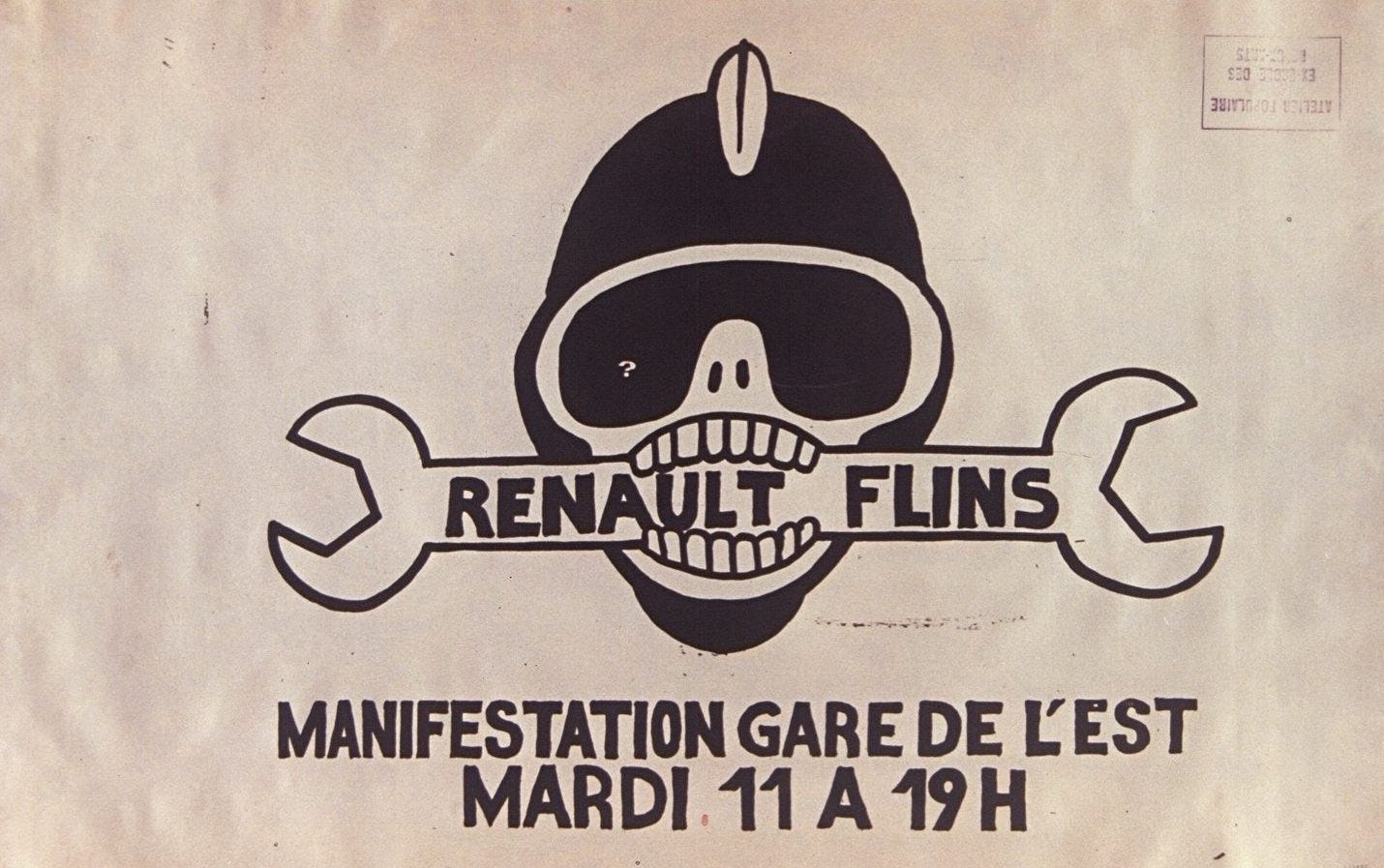

But fought over they were. On 22 March 1968, Situ-influenced students occupied the administration block at Nanterre University, leading to weeks of protests and the closure of the University for two days. The closure spread the protests to the Latin Quarter and the Sorbonne, which was also occupied. In the course of three days in occupation of the Sorbonne, the Situationists sent telegrams to every factory and union they could think of. In the weeks following there was large-scale street fighting, a general strike, and occupation by workers of the Sud-Aviation plant in Nantes. Supporters of the Enragés and the Situationists in Paris formed the Council for Maintaining the Occupations (C.M.D.O.). With its aim to promote autonomous ‘councilism’, the C.D.M.O. organized the printing of large numbers of pamphlets and posters in occupied print shops. Naturally, not being vanguardists, they didn't credit these artefacts as the work of the Situationists, but they did the work anyway, and the rest, so to speak, is history.

Debord dissolved the Situationist International in 1972 because he recognised that, as the S.I.'s ideas had become so influential globally that there was a danger of the ideas being recuperated. The S.I., whilst approving in principle of revolutionaries organising in autonomous groups, did not want to become yet another political sect claiming to 'represent' the forces of revolution.

Continued next week

David Black’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Cheers GIN. I'm continuing the series on the strange days over the next few weeks

What a good wink from the Unicorse. It was only last night that I wrote I have been thinking about the situationalists these strange daze. The need for play & correct absurdities abounds.