In 1945, Isodore Isou, a 20-year old Jewish refugee who had managed to survive Nazi-occupied Rumania, arrived in Paris with a headful of ideas about modernism - especially Dada and Surrealism - and kabala. In November, he founded the ‘Letterist’ movement with another Holocaust survivor, the French poet, Gabriel Pomerand. In 1946 Isou and the Letterists disrupted a performance of Dadaist Tristan Tzara's La Fuite. Isou shouted at his fellow Rumanian ‘Dada is dead! Lettrism has taken its place!"

In 1947, Gallimard, a major Paris publishing house, put out a book by Isou entitled Introduction d’une nouvelle poésie et d’une nouvelle musique. In it Isou analyzed poetic language as having gone through an ‘amplification’ process in the romantic period, followed by a ‘chiseling’ process in the modernism of Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Mallarme, until Dada finally destroyed it. Once the chisel of history had done its work, the truth and beauty of poetic language was no longer to be found in words, but in letters, representing figures and sounds. Isou and the Letterists experimented with sound-poems, paintings, music and film. Isou also wrote about his sexual prowess, which made him even more controversial, and drew the attention of the censors.

Isou was effective in promoting, by fair means or foul, the Letterists (or ‘Lettrists’) as the new avant-garde. In January 1947, the New York Times Paris correspondent, John Lackey Brown, wrote,

‘A band, led by a 21-year-old Romanian whose pen name is Isidore Isou, has created “lettrism.” The lettrists, determined to do Dada and the Surrealists one better, aim at the renovation of poetry not only by the invention of new words but of new letters. So far they have invented 18.’

The Letterist rebellion conceived in a time of barbarism, was a denial of the separation between art and life. In a manifesto for a ‘Youth Front’, Isou hailed the youth of France as a sort of sub-proletariat: excluded from consumerism by low pay or unemployment; alienated from the church, especially in education; and oppressed by the archaic French Penal Code. The first act of the Youth Front was a riotous attack on the brutal staff at an infamous Catholic orphanage, which ended in arrest and imprisonment for some of the youth.

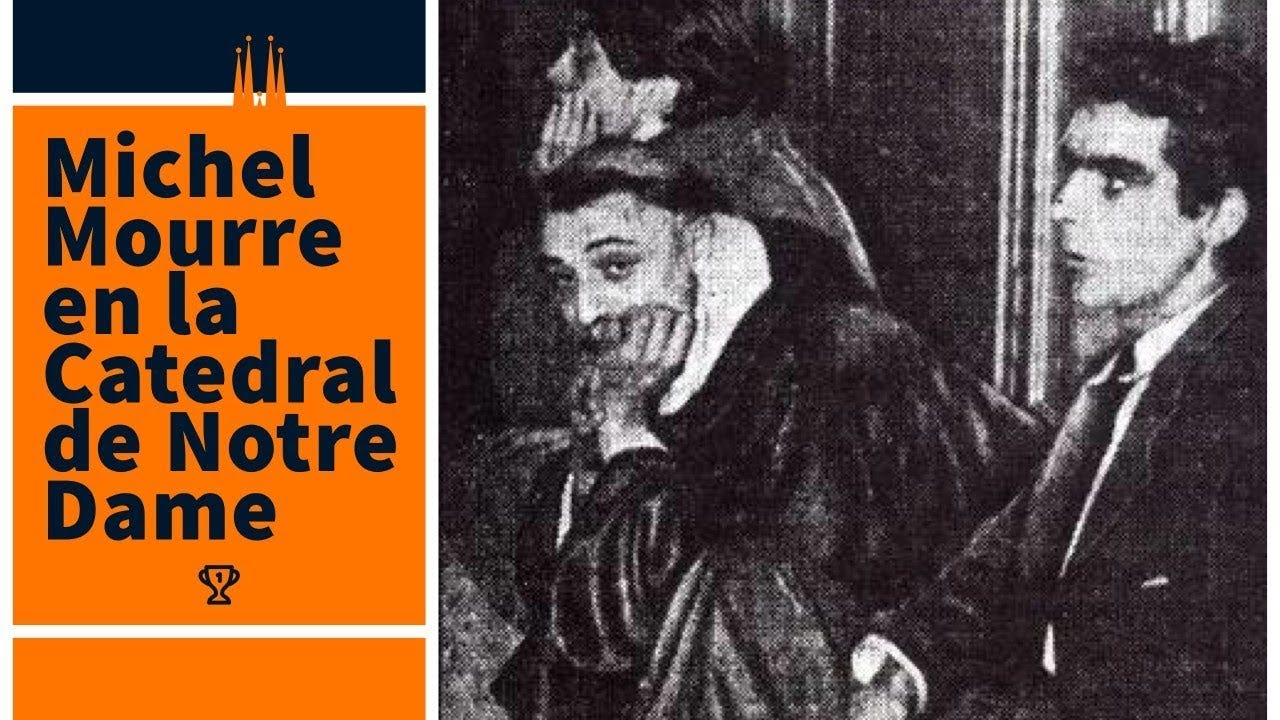

In a similar spirit, in 1950, a group of Letterists led by Michel Mourre, disguised as a Dominican monk, disrupted Easter Mass at Notre Dame by reading out a ‘God is Dead’ statement. They were attacked with swords by the Swiss guards and almost lynched by the congregation before the police came to the rescue and arrested them.

In the field of poetics, Isou attempted to extend the ‘chiseling’ concept to cinema with his Traite de bave et d’eternite (Treatise on Bile and Eternity). Premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1951, it was booed by the audience and nearly caused a riot. This was, not least, because Isou hadn’t actually completed the film, so that for 90 minutes the audience was subjected to the soundtrack in total darkness.

The finished film attacks cinematic language. Isou introduces discrepancy between the soundtrack and the images on the screen; and projects the physicality of the celluloid itself, sculpted with scratched images and corrosive bleach. Narrative is constantly disrupted by gestures of Sadean offensiveness. The power of sound poems and images is a real cinematic innovation, casting a spell that evokes both annoyance and admiration. Isou’s voice on the soundtrack intones: ‘I announce the destruction of the cinema, the first apocalyptic sign of disjunction, of rupture, of this corpulent and bloated organization which calls itself film.’ The film was praised by Cannes jury member, Jean Cocteau and in Cahiers du Cinéma by the young director, Éric Rohmer, and by the American experimental filmmaker, Stanley Brakhage.

In 1952 Guy-Ernest Debord and Gil Wolman, both filmmakers, several years younger than Isou, joined the Letterists. In Debord’s film of 1952, Hurlements en faveur de Sade (Howlings for de Sade) the soundtrack consists of Letterist sound-poems, howls, quotations from the French penal code, and from movies and literature. The blank white on the screen turns repeatedly to black, and stays black for the silence of the final 24 minutes. The Hurlements soundtrack features Guy Debord’s first vocal articulation of the future Situationist project:

‘The arts of the future can be nothing less than disruptions of situations... A science of situations needs to be created, which will incorporate elements from psychology, statistics, urbanism, and ethics. These elements must be focused on a totally new goal: the conscious creation of situations.’

The script for Hurlements was published in the Lettrist journal, Ion, in 1952. It refers to images of conflict that never made it into the finished product: rioters fighting police; imperial armies in India, Indo-China and Algeria; and a naval battle in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. The screenplay thus prefigures the use of war footage and Hollywood representations of war in Debord’s later films, such as Sur le passage de quelques personnes (1959) and Critique de la séparation (1961). At the first screening of Hurlements, in Paris at the Ciné-club du Quartier Latin, those who stayed to complain rather than walk out were bombarded by insults and water-bombs thrown by Letterists from the balcony. Those who felt cheated by the misleading title of the film found themselves, literally, ‘howling for de Sade.’

Gil Wolman’s film, Anti-Concept (1952), features his improvised sound-poems along with the alternating blackness and whiteness effect. It was banned by the local prefecture, because, not understanding it, they couldn’t be sure that it wasn’t subversive or indecent.

One of Isou’s most powerful insights in Traite de bave et d’eternite is expressed in his statement that,

‘The history of cinema is full of corpses with a high market value... Screens are mirrors that petrify the adventurous by returning their own images to them and halting them in their tracks. If one cannot pass through the screen of photography to something deeper then cinema holds no interest for me.’

It was the something deeper that Debord and Wolman were interested in. It soon occurred to them that Isou’s chiseling of poetry down to letters had already reached the dead end Surrealism had found itself in with automatic writing.

Debord and Wolman’s break with Isou was precipitated by the ‘Chaplin Affair’. In 1952, at the Paris premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight, Debord and Wolman handed out a statement which ended with the words: ‘the footlights have melted the make-up of the supposedly brilliant mime. All we can see now is a lugubrious and mercenary old man. Go home Mister Chaplin’. As Chaplin had been barred from the United States for suspected ‘communist’ sympathies, he had become a cause celebre of the Left, including leading Surrealists. What made Chaplin him fair game for the Letterist counter-welcome was that he had accepted a medal from the local Chief of Police. They saw the consensus love-fest around Chaplin as fake: a cover-up of the real divisions in French politics on such basic issues as fascism and imperialism. The Chaplin incident was too much for Isou, who at first praised it, but then backtracked and denied all responsibility. Debord and Wolman took this as their cue to break with Isou and form a rival Letterist group, which they named the ‘Letterist International.’

Unlike the rest of the avant-garde, the Letterist International refused to be ‘answerable’ to the court of art criticism and the gaze of the ‘other’, refused to seek fame, and refused to market anything they produced. The L.I.’s mimeographed journal, Potlatch, appeared in 20 issues between June 1954 and November 1957. With an eventual print run of 500 copies, was always given away free to friends of the group, or mailed to people who expressed an interest.

In July 1957, at a conference in Cosio d’Arroscia, Italy, the Situationist International was founded by Guy Debord and Michèle Bernstein of the Letterist International; along with various painters from Surrealist backgrounds: from England, Ralph Rumney; Denmark, Asger Jorn; Italy, Guiseppe Gallizio) along with musical composer, Walter Olmo; and Piero Simondo and Elena Verrone of the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus..'

CONTINUED NEXT WEEK