'Balzac was the first to speak of the ruin of the bourgeoisie. But it was surrealism which first allowed its gaze to roam freely over it.' - Walter Benjamin

‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities.’ - Delmore Schwartz

In 1924, André Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto and founded the magazine La Révolution Surréaliste and the Bureau of Surrealist Research. Influenced by Freud’s ideas on the interrelation of the conscious and the sub-conscious, Surrealism had, in the words of Walter Benjamin, recognized that the 'residues of the dream-world' lay scattered amongst the products of bourgeois consumer culture. The idea was that these objects and images could be utilized by poetic invention. In a concrete unity of subjective and objective experience, Surrealism, in creatively deviating the objects of the world from their accepted roles and properties, was an expression of dialectical thought in the organic process of historical awakening. In Benjamin’s words::

'Every epoch not only dreams the next, but while dreaming impels it towards wakefulness. It bears its end within itself, and reveals it – as Hegel had already recognized – by a ruse. With the upheaval of the market economy, we begin to recognise the monuments of the bourgeoisie as ruins even before they have crumbled.'

In 1930, André Breton published a French translation of parts of Lenin’s previously unknown Notebooks on Hegel’s Science of Logic in the journal Le Surrealisme au Service de la Revolution. Breton himself made a study of Hegel’s Aesthetics in order to trace the historical dialectic in Art.

Hegel sees poetry, as the most universal art, having proved itself capable as representing all of the stages of historical life, and as superior to the prosaic. In Romanticism, the poetic art comes into its own – and also reaches its limit. The true content of Romantic thought is absolute internality in the form of conscious and free personality. As the universal, representing the wholeness of life, it is the absolute negativity and dissolution of all that is finite and particular: 'In this pantheon all the gods are dethroned. The flame of subjectivity has consumed them.'

It was the fate of Romantic art that its sensuous, material character could no longer provide the means to express the ideal content it depends upon in order to exist as art. For the romantic, the ideal eventually becomes the object which is revealed to the 'inner' self. But since 'the spiritual has now completely retired from the outer mode into itself', the 'sensuous externality of form' it assumes becomes impoverished, with 'an insignificant and transient character': 'Feeling is now everything. It finds its artistic reflection, not in the world of external things and their forms, but in its own expression.'

Hegel says that 'as regards its highest vocation, art is and remains for us something past. For us it has lost its genuine truth and vitality; it has been displaced into the realm of ideas…'

What is aroused in us by art beyond immediate enjoyment is 'the judgment that submits the content and medium of representation of art to reflective consideration...the science of art is a far more important requirement in our own age than it was in earlier times when art s1imply as art could provide complete satisfaction.”

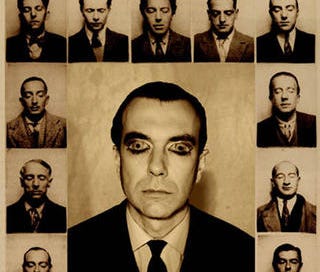

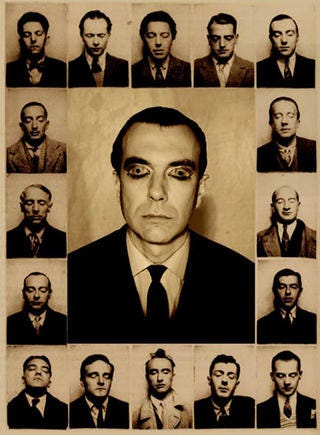

René Crevel (1900-35) saw Hegel as an ally against Romanticism’s attempts to obliterate the world in its own subjective anguish. The narcissistic individual, in devouring the universe and suppressing its objects, 'becomes himself the object, and not only becomes insufficient but destroys himself… [and] succumbs before the mirror he questioned... the most mediocre, the most vain, the most superficial of waters.'

Crevel’s comrade, Andre Breton saw in Hegel’s aesthetics a brilliant insight into the poetic personality’s overcoming, through 'objective humor', of romanticism’s 'servile imitation of nature in its accidental forms'. Given the repeated efforts of modern art to escape from servile imitation in the movements of Naturalism, through to Impressionism, Cubism, Futurism and Dadaism, Hegel’s assertions had a 'tremendous prophetic value'. Hegel’s speculative idealism, in refusing to recognize any force outside of concrete mental and material reality, had envisioned a revolutionary and objective reconciliation of human becoming and its universe – a true solution to the ‘crisis of the object’. In the Second Surrealist Manifesto (1930) Breton recommitted the movement to the absolute reconciliation of opposed states:

'Everything tends to make us believe that there exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions. Now, search as one may, one will never find any other motivating force in the activities of the Surrealists than the hope of finding and fixing this point.'

The first of the ‘-ist’ manifestos of modernist avant-gardes had been Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto of 1909, which celebrated technology, war and misogyny: ‘We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.’

By 1930, Marinetti was trying to become to Mussolini what Musk is trying to become to Trump. In 1930, avant-gardists of the Left, who opposed the fascist exaltation of mechanised violence, questioned Breton’s wisdom when he wrote in the Second Surrealist Manifesto:

‘The simplest surrealist act consists, with revolvers in hand, of descending into the street and shooting at random, as much as possible, into the crowd.'

Breton, while serving in the First World War as an medical orderly in a neurological ward for shell-shocked pollus, became aware of Freud’s discoveries on the power of the unconscious in relation to neurosis. In Hegelian terms, everything ‘simple’ is a mis -recognition in the process of enlightment. For Breton, lived reality itself had become surreal, and needed to be transcended Au Service de la Revolution. Breton later qualified his words:

'While I say that this act is the simplest, it is clear that my intention is not to recommend it to all merely by virtue of its simplicity; to quarrel with me on this subject is much like a bourgeois asking any non-conformist why he does not commit suicide, or asking a revolutionary why he hasn't moved to the USSR.'

CONTINUED NEXT WEEK