'Cad!' How to Provoke a Nationalist

George Orwell on why it's OK to be a 'patriot'

Benedict Anderson’s book of 1983, Imagined Communities, is still the go-to text for studying the origin and spread of nationalism. Less read and almost forgotten is George Orwell’s essay ‘Notes on Nationalism’, written for Polemic magazine just after V.E. Day in May 1945 (republished in The Penguin Essays Of George Orwell. 1994.)

Orwell contends that the nationalistic way of thinking is replicated in various political and religious ‘isms’ in which sound political and moral judgement are lacking. 80 years on, his arguments, which I discuss below, remain challenging.

Following the Declaration of War in September 1939, Britain drifted into the ‘Phoney War’, which ended abruptly in June 1940 with the German conquest of France and the hasty evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk. Although Neville Chamberlain’s pre-war appeasement policy had been discredited as a strategy for preventing war, it lingered amongst fascists and some Tories. who saw the Axis of Hitler. Mussolini and Franco as a bulwark in the world struggle against ‘Judeo-Bolshevism’. On the Left, neutrality was favoured by communists, who at the time supported the Stalin-Hitler Pact, and by pacifists who believed that the British Empire was ‘objectively’ as bad as the Third Reich and therefore shouldn’t be supported militarily.

George Orwell was in favour of the war from the start, but argued that the Colonel Blimps of the military couldn’t win it, and that appeasing Tories in high places who opposed it might yet unleash fascist violence against the working class. Orwell endorsed and joined the Home Guard which he hoped might, given the right circumstances, morph into something not unlike the anarcho-marxist militia he had served with in the Spanish Civil War. As he put it in ‘My Country Right or Left’ (Folios of New Writing, Autumn 1940):

‘To be loyal both to Chamberlain’s England and to the England of tomorrow might seem an impossibility, if one did not know it to be an everyday phenomenon... we shall see changes that will surprise the idiots who have no foresight. I dare say the London gutters will have to run with blood. All right, let them, if it is necessary. But when the red militias are billeted in the Ritz I shall still feel that the England I was taught to love so long ago and for such different reasons is somehow persisting.’

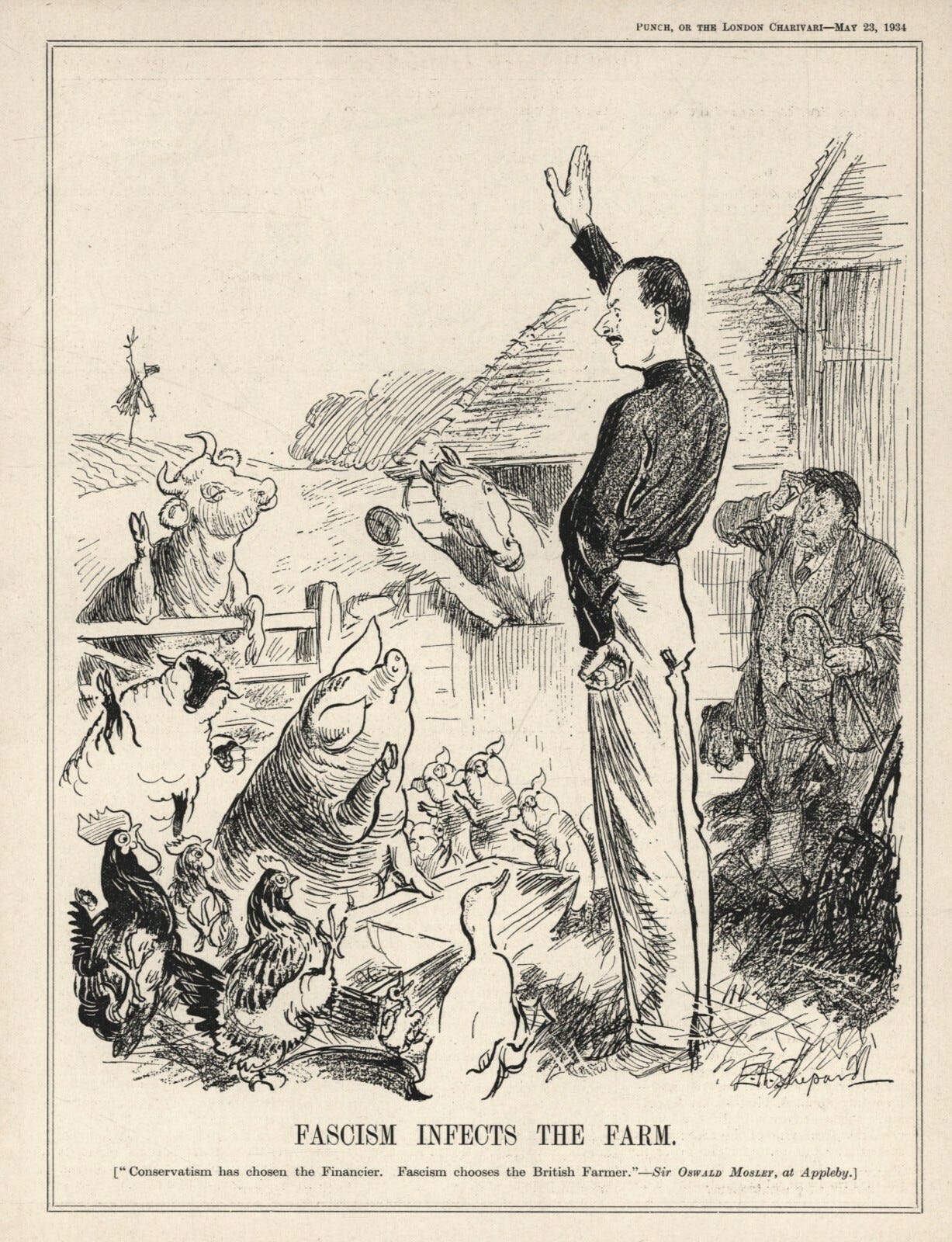

Five years into Wartime England, and with the downfall of Hitler, it became clear to Orwell that the Tories, having re-asserted their power, now seemed as patriotic as their Labour coalition partners. Hitler’s sympathisers in the Conservative Party had been shoved aside and silenced by the Churchill-led ‘One Nation’ Tories, and Mosley’s fascist party suppressed. Orwell abandoned his earlier position on the ‘red militia’, if not his commitment to socialism. In any case, the experience of the war called for a new assessment of nationalism.

Orwell notes that nationalists have a ‘habit’, often casually expressed, of classifying human beings as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ according to language or geographical location. In a wider, ideological sense, the ‘nationalist’ believer self-identifies with a ‘single nation or other unit’ and serves to uphold its interests beyond questions of good and evil.

Nationalism, according to Orwell, is not the same as patriotism, which he defines as: ‘devotion to a place or particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people. Patriotism is by its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally.’ Nationalism, in contrast, is inseparable from the desire for power:

‘Nationalism, in the extended sense in which I am using the word, includes such movements and tendencies as Communism, political Catholicism, Zionism, Antisemitism, Trotskyism and Pacifism. It does not necessarily mean loyalty to a government or a country, still less to one’s own country, and it is not even strictly necessary that the units in which it deals should actually exist.’

In the 1930s Stalin’s retrenchment of Russian nationalism as ‘Socialism in One Country’ was marked in the West by Popular Frontism, which many intellectuals supported. Orwell points out that ten years earlier many intellectuals had embraced political Catholicism, which like the political Islam of later times opposed the Ideal to political reality. G.K. Chesterton attacked British Anglican Toryism while supporting the rule of fascists like Mussolini in Catholic countries. Chesterton’s readers inhabited a fantasy world of an altered past ‘in which, for example, the Spanish Armada was a success or the Russian Revolution was crushed in 1918 — and he will transfer fragments of this world to the history books whenever possible.’ Catholics and Stalinists alike, in rewriting history ‘do probably believe with part of their minds that they are actually thrusting facts into the past’:

‘When one considers the elaborate forgeries that have been committed in order to show that Trotsky did not play a valuable part in the Russian Civil War, it is difficult to feel that the people responsible are merely lying. More probably they feel that their own version was what happened in the sight of God, and that one is justified in rearranging the records accordingly.’

If one harbours anywhere in one’s mind a nationalistic loyalty or hatred, then certain facts, although in a sense known to be true, are inadmissible. In a Parliamentary debate on the Boer War (1899-1902). Liberal leader Lloyd George pointed out that government communiques claimed numbers of enemy killed that exceeded the entire Boer population. Tory Prime Minister Arthur Balfour didn’t challenge the factual accuracy of Lloyd George’s mockery, which implied a cover-up of the massive civilian death-rates caused by the scorched earth and internment strategy. Instead, Balfour rose to his feet and shouted ‘Cad!’ Orwell comments:

‘Very few people are proof against lapses of this type… One prod to the nerve of nationalism, and the intellectual decencies can vanish, the past can be altered, and the plainest facts can be denied.’

Indeed, denials of reality have persisted, as more recently when those who opposed the 20-year war Afghanistan, arguing that it had been lost from the start, were denounced as soft on terrorism.

As Orwell puts it, facts which are ‘grossly obvious’ are often intolerable to such mindsets, be they of atavistic Tories, Stalin-worshipping communists, romantic Celtic nationalists, or sectarian Trotskyists. In such cases the facts ‘have to be denied, and false theories constructed upon their denial’:

‘The point is that as soon as fear, hatred, jealousy and power worship are involved, the sense of reality becomes unhinged. And… the sense of right and wrong becomes unhinged also. There is no crime, absolutely none, that cannot be condoned when “our” side commits it. Even if one does not deny that the crime has happened, even if one knows that it is exactly the same crime as one has condemned in some other case, even if one admits in an intellectual sense that it is unjustified — still one cannot feel that it is wrong. Loyalty is involved, and so pity ceases to function.’

Some of the ‘worst follies’ of intellectual ‘nationalism’ can be attributed to the breakdown of religious belief and traditional patriotism. Chesterton believed organised religion was a guard against pagan superstition: ‘When men choose not to believe in God, they do not thereafter believe in nothing, they then become capable of believing in anything’. Royalists see the monarchy - currently being exposed as a giant fraud, long past its sell-by date - as a safeguard against dictatorship (former Prime Minister Ted Heath, when asked to explain how he could be both a monarchist and a democrat, answered ‘Two words: President Thatcher’).

Another alternative is to argue that ‘no unbiased outlook is possible, that all creeds and causes involve the same lies, follies and barbarities; and this is often advanced as a reason for keeping out of politics altogether.’ OrwelI’s rejoinder to such quietism is that while most of us harbour nationalistic passions as part of our make-up, whether we like it or not, it is possible to struggle against them with an essentially ‘moral effort’.

‘It is a question first of all of discovering what one really is, what one’s own feelings really are, and then of making allowance for the inevitable bias… you can at least recognise that you have them, and prevent them from contaminating your mental processes. The emotional urges which are inescapable, and are perhaps even necessary to political action, should be able to exist side by side with an acceptance of reality.’

80 years on the emotional urges are plugged into electronic communication platforms driven by algorithms which aim to manufacture a spectacular pseudo-reality along with ‘consent’ and ‘acceptance’. In the 21st century there are new words and terms on the block to fight over - campism, identity politics, culture war, wokeness, etc - but ‘acceptance of reality’ and consensus of what ‘reality’ actually might be is as elusive as ever.

Very good analysis. One thing I am beginning to find strange about the whole nationalist anti-asylum movement now is that it’s single men who are now coming over on these illegal boats run by criminals. Some may have families - but it’s hard to know who they are. The checks and balances of EU open borders have gone - not that they were perfect. These are now practically all young Muslim men! I have friends in Walthamstow - a number of women who tell me these men do harass them for sexual purposes - coming up to them in the street - young and old. Maybe this is nothing to do with nationalism? I do not know.