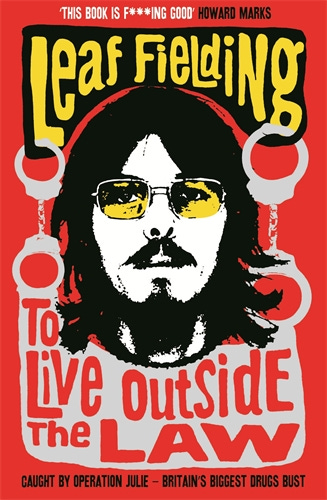

‘Leaf’ Fielding, author of the autobiographical To Live Outside the Law: Caught by Operation Julie, Britain's Biggest Drugs Bust has died. This is some of what I wrote about him in my book LSD UNDERGROUND: Operation Julie, the Microdot Gang and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love:

In 1971, Brian Cuthbertson of the ‘Microdot Gang’ recruited Leaf Fielding, a dope-smuggling anarchist he had known at Reading University, to tablet the LSD. Fielding recalled:

In the 60s I was an ‘acid freak’ – one of a group centred around Reading University whose lives had been transformed by the powerful psychedelic. Acid had, we thought, given us a collective vision of a saner, safer future, one where human interactions would not be based on fear, greed and coercion.. Unlike many similar groups throughout the country, we did not confine ourselves to talking. In 1970, together with a bunch of similarly-minded people from Cambridge, we began to manufacture and distribute small quantities of LSD. Our conspiracy was on its way.

At his interview for the tableting job, distribution manager Henry Todd asked Fielding, ‘What do you think about acid?’ Fielding replied: ‘Acid isn’t susceptible to easy analysis. Let’s see... LSD is probably the best hope the human race has got of coming to grips with its problems.’ Todd responded, ‘Fair enough. I think pretty much the same myself.’

Todd then proceeded to explain the security arrangements befitting the ‘very high stakes’ they were playing for. The arrangements were certainly those befitting of a secret underground organisation. Shopping bags containing thousands of newly minted tablets were exchanged for bags containing pure crystal acid for the next tableting run in such genteel settings as the teashop next to the entrance to Kew Gardens (‘amazing cakes and scones’): ‘If one of us doesn’t make it we default to a fall-back option four hours later.’ A phone call arranging a meeting for a chat at the pub at five on Saturday meant meet at the pre-arranged rendezvous at three on Thursday. The only organisation to be spoken of was Todd’s business front, Intertrans. Hippie dress was ruled out; only business suits and short haircuts were in order.

Another Intertrans recruit, known as ‘Chip’ was assigned to work with Fielding on tableting. Together they rented a flat in Fulham to live in and a bedsit in Oxford Street for the tableting operation. Their first run produced 40,000 micro-cubes from ten grams of crystal. Several other runs followed. Security required that they didn’t stay in any one place for too long. They moved from Fulham to Twickenham, and moved the tableting operation from Oxford Street to Richmond.

Tableting LSD was dangerous work, requiring masks and rubber gloves to protect against contamination. One day Chip was contaminated through sleeping on a pillow that had absorbed LSD from his hair. He had a very bad trip, vowed never to take drugs again, and quit. Weeks later it was Fielding’s turn to overdose. In his book he describes what happened after he absorbed a massive dose of LSD which got into a cut in his hand through a tear in a rubber glove:

The floor was a mass of writhing tendrils. I sank down into it, unable to move for over four million years. Generations grew up, grew old, died and were reborn on the little rock spinning around a fire in space. Through the confetti of millennia I grew tired of the interminable human story, but it rolled inexorably on and on, cruelty upon kindness upon cruelty, until mercifully at the smoking end of time, Lord Shiva danced the world out of existence.

The venture grew into an underground industry, supplying the festival-going youth of the 1970s with tens of millions of acid trips. The police eventually rounded up most of the gang’s principals in March 1977 in what the media hailed as the ‘biggest drugs raid in British history’. On 8 March 1978, at Bristol Crown Court, 29 defendants were handed down prison sentences totalling 170 years, with the sentences for the 17 principal defendants amounting to 133 years. Leaf Fielding got 8 years. Richard Kemp, the group’s chief chemist, got 13. Whilst on remand in Her Majesty’s Prison Bristol, in 1977, Fielding met Kemp:

Richard was a man after my own heart. We talked long and excitedly in one-hour bursts. He too had wanted to turn the world on and he’d gone a long way towards achieving his aim by producing kilos of acid, enough for tens of millions of trips...

‘And look where our idealism got us.’

His despondently waving arm took in the prison walls, D wing and the punishment block.

‘Well we’re not the first people to be persecuted for what we believe in,’ I replied, ‘and I don’t suppose for a moment we’ll be the last. We’ll be exonerated in the future, don’t you think?’

‘Maybe. But that doesn’t help us now.’

The bell brought another exercise period to an end.

(Leaf Fielding, To Live Outside the Law)

After serving his sentence Leaf Fielden worked as teacher in Spain, set up a home for orphans in Malawi, and the moved to the south of France where he sold organic vegetables.

Yusuf, I say Leaf Fielding was an anarchist because that's precisely how he describes himself in his autobiography, To Live Outside the Law, chapter 4 'Summer in the Sixties'

It is interesting that you wrote this piece just a few days after my husband, Leaf Fielding, died. Were you aware of his demise? He had been suffering from Altzheimer's for about eight years. He was an anarchist in the pure sense of the word, not the popular misconception. ( ..... anarchists do not seek to create chaos or disorder. Rather, they aim to create a society that is organised and functional, but without the need for external authority or coercion.) I share his views.