In February 1881, Vera Zasulich wrote to Marx from Geneva, asking him whether ‘the [Russian] rural commune, freed of exorbitant tax demands, payment to the nobility and arbitrary administration, is capable of developing in a socialist direction’ or whether ‘the commune is destined to perish’.

As it happened, Marx was deeply concerned at this time with the issue of rural communism: he had been reading Maxim Kovalevsky’s Common Landownership: The Causes, Course and Consequences of Its Decline, Lewis H. Morgan’s Ancient Society, James Money’s Java, or How to Manage a Colony, John Phear’s The Aryan Village in India and Ceylon and Henry Maine’s Lectures on the Early History of Institutions. Marx’s first draft reply to Zasulich states:

‘If the revolution takes place in time, if it concentrates all its forces to ensure the unfettered rise of the rural commune, the latter will soon develop as a regenerating element of Russian society and an element of superiority over the countries enslaved by the capitalist regime.’ (emphasis mine)

Kohei Saito claims in his best-selling book, Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism, the use of the word ‘superiority’ in this context suggests Marx’s view of history had changed by 1881, in that he explicitly acknowledged the power of Russian rural communes to bypass capitalist modernization.

Saito refers to Kevin B Anderson’s ‘path-breaking investigation of Marx’s Notebooks’ in Marx at the Margins; on Nationalism, Ethnicity and Non-Western Societies’ but adds, ‘To put it bluntly, Marx’s primary interest was not to establish the law of history [or]... test the applicability of his law.’

Anderson, however, refers to a ‘theory of history’, not the ‘law of history’. The only other reference to ‘law of history’ in Saito’s book comes earlier on in his text regarding Lukacs’s critique of Engels’s ‘positivism’: ‘...if a laboratory experiment is understood as the dialectical practice, as Engels seems to believe, its application to society would lead to a mechanistic understanding of the objective law of history.’

In Hegel’s case, a universal theory or a philosophy of history is based on the dialectic of freedom and reason. History had shown that selfish, impulsive desires served as more effective ‘springs of action’ than ‘benevolence’ of a ‘liberal or universal kind’. Hegel rejects as ‘vain’ all attempts ‘to solve the enigmas of Providence’, or to explain the evil, vice and ruin that marks world history as purely ‘the work of mere Nature’ without taking into account the human factor. For ‘the Human Will — a moral embitterment — a revolt of the Good Spirit (if it have a place within us) may well be the result of our reflections.’ (GWF Hegel, The Philosophy of History, §24)

In February 1881, Marx wasn’t just reflecting on his ethnological studies of ‘archaic’ forms of rural communism. He was also concerned with the impact of his ideas on Russian revolutionaries, who were very activated by ‘the Human Will — a moral embitterment — a revolt of the Good Spirit’.

Marx was somewhat disarmed by the invitation from Zasulich to clearly state his views on the peasant rural communes in the pages of her organisation’s paper - hence the four drafts he made before writing his reply. Zasulich’s party, Black Repartition, was led by intellectuals who looked to historical materialism for validation of their position that capitalism was coming to Russia and that there would be no effective base in the peasant communes for socialist politics. The leaders were Geneva-based exiles, whom Marx was somewhat disdainful of because they exuded the over-cautious quest for respectability that was already evident in west European social democracy.

Black Repartition emerged following a split in 1879 in the Land and Liberty party. Their adversaries in the split were the Narodniks, who went on to found People’s Will. In contrast to the legalistic tactics of Black Repartition, the Narodniks were fighting the Czarist state with a terrorist campaign. But the Narodniks were also serious thinkers, who drew their ideas from leading intellectuals whose works were studied closely by Marx, notably Herzen, Chernyshevsky, Lavrov and Mikhaylovsky. Marx admired the Narodnik cadre, because they were active, courageous revolutionaries.

When the Narodniks carried their agitation to the countryside, they found that the mass of the peasants were under the sway of Czar-worship, enforced by a repressive state and by an Orthodox church which was especially hostile to the Narodniks’ militant feminism. The intensification of the Narodniks’ terrorist campaign was intended to break the passivity of the peasantry by attacking the State and thus exposing the mirage of its invincibility.

On 8 March 1881, Marx sent a cautiously worded reply to Zasulich. After initially writing a 4,500-word draft, he had whittled it down to 350 words, the main point being that his analysis in Capital provides ‘no reasons either for or against the vitality of the Russian commune.’ He elaborates:

‘But the special study I have made of it, including a search for original source material, has convinced me that the commune is the fulcrum for social regeneration in Russia. But in order that it might function as such, the harmful influences assailing it on all sides must first be eliminated, and it must then be assured the normal conditions for spontaneous development.’

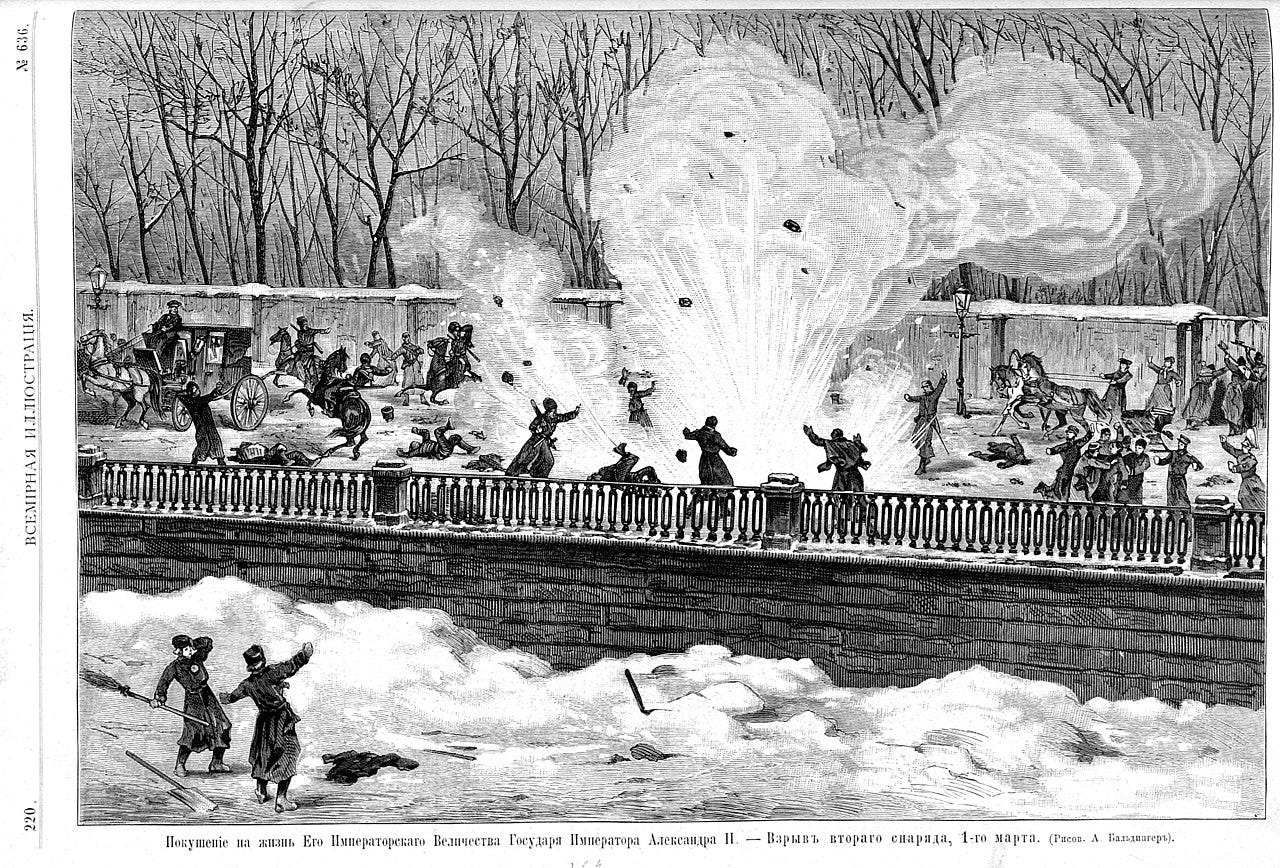

A week before he sent this letter, the Narodniks had assassinated Czar Alexander II. Marx and Engels, who hated Russian Czarism more than any despotism in the world, celebrated the assassination and hoped, as did the Narodniks, that it might even spark a revolution. It didn’t, and in response the Russian state unleashed a wave of repression. Nevertheless, 10 months later, in the January 1882 preface to the Russian edition of the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels claim that, as ‘Russia forms the vanguard of revolutionary action in Europe’, the new Czar, Alexander III, was ‘a prisoner of war of the revolution’ holed up in the Great Gatchina Palace at Saint Petersburg. They conclude:

‘Now the question is: can the Russian obshchina, though greatly undermined, yet a form of primeval common ownership of land, pass directly to the higher form of Communist common ownership? Or, on the contrary, must it first pass through the same process of dissolution such as constitutes the historical evolution of the West? The only answer to that possible today is this: If the Russian Revolution becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting point for a communist development. ‘

Saito comments: ‘Thus, Marx and Engels cautioned that the Russian communes could not only avoid going through the capitalist stage but even demanded that they initiate communist development by sending “the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West”.’(195-96) Saito, referencing Haruki Wada’s Marx, Engels and Revolutionary Russia, points out that this was contrary to Engels’s position of 1875, which emphasized the need for a Western proletarian revolution as a condition for the success of Russian revolution. (212-13) Saito writes:

‘By carefully investigating the reason why he had to study pre-capitalist societies and natural sciences at the same time, a new and surprising possibility of interpreting Marx’s letter to Zasulich emerges: Marx ultimately became a degrowth communist’(173)

Saito sees in Marx’s correspondence and research during his last years an ‘epistemological break’ (‘in the Althusserian sense’) in which he ‘finally’ rejected Promethean productivism: ‘The degrowth communism that Marx was hinting at in the last stage of his life was not an arbitrary interpretation, considering his passionate endorsement of the Narodniks.’(209) But if this rests on the claim that Marx saw peasant communes in Russia, India and elsewhere as the definitive field of class struggle in those lands, which would act as the ‘signal’ for revolution by the proletariat of the West, it has to balanced against his speculation that the two could ‘complement’ one another, with the implication (which Saito would presumably accept) that both would have to be revolutionised by a non-productivist, humanised path of modernisation.

The impoverishment of the peasantry by encroaching capitalism and the growth of intensely exploitative industrial production meant Russia was in a state of permanent social crisis, which raised the likelihood, sooner or later, of revolution. How and when it might come could not of course be prophesized. Marx was keen to clarify his ideas in the context of subjective-objective developments in Russia, in which the Narodnik left was itself in a state of long-term crisis. For, if the survival of the peasant communes couldn’t be sustained, as seemed increasingly likely, then the terrorist tactics would have to be re-assessed. In 1887, Aleksandr Ilyich Ulyanov of People’s Will was convicted of making dynamite bombs in a failed plot to assassinate Czar Alexander III and was hanged along with four co-conspirators. His younger 17-year old brother was the future leader of the Bolsheviks, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

This is an extract from a review of Kohei Saito, Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism (Cambridge University Press, 2022. Paperback: ISBN-13978-1-009366182), entitled How Green was Karl Marx? On Kohei Saito and the Anthropocene by David Black