(The previous post looked at how the oppositions expressed in mystery cult – between limited and unlimited, individual and community, and fragmentation and wholeness – may provide, as Richard Seaford speculates, a ‘traditional model’ for the oppositions in money, as projected by the philosophers.)

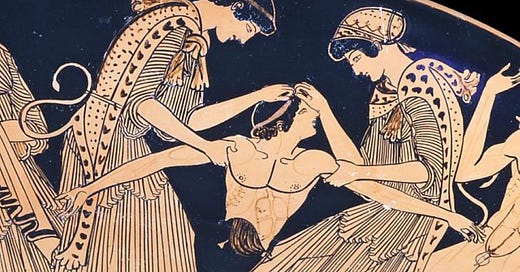

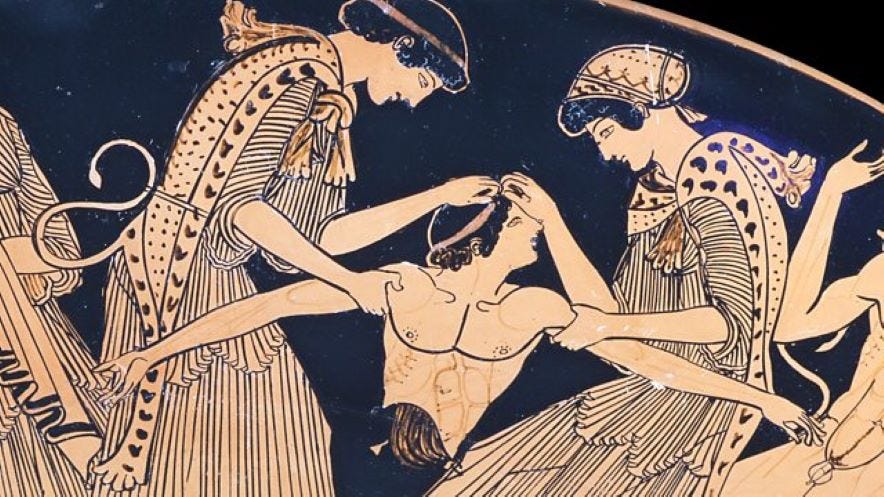

In the Eleusinian ritual, the initiate, under the guidance of the hierophantes, is made to experience alternately, light and darkness, and hope and fear. In experiencing a divine intimacy with the Goddesses, he shares their sufferings and partakes of their sublime higher existence. According to the Roman Bishop Hippolytus, the climax of the Eleusinian vision is the initiate being shown an ear of ripe corn, which represents the power of the earth mother. Aristotle says of the cult of Orphism that the initiate ‘was not expected to learn or understand anything, but to feel a certain emotion and get into a certain state of mind, after first becoming fit to experience it.’

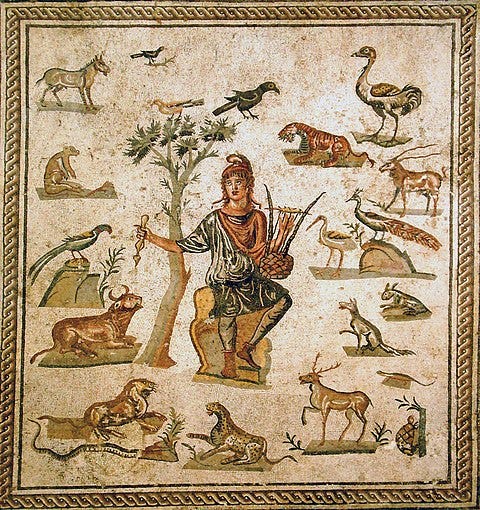

Whereas the Olympian gods are daemons of particular localities, the mystery gods, Dionysus and Orpheus, are daemons of human groups. The function of mystery cults is, strictly religious and organised as a secret society into which admission takes place through initiation rites.

The intoxicating spirit of Dionysus is human; the rituals of his worshippers (thiasmos) draw the god into the group and make the individuals lose themselves in the community of the divine and the One. As Cornford puts it,

“Orgiastic ritual ensures that Dionysus, even when his worship was contaminated with Olympian cults, never became fully an Olympian. His ritual, by perpetually renewing the bond of union with his group, prevented him from drifting away from his province, as the Olympians had done, and ascending to a remote and transcendental heaven. Moreover, a mystery religion is necessarily monotheistic or pantheistic.”

For the cult of Dionysus, human existence is the cyclical life of the seasons. The conceptual framework is thus temporal, rather than spatial. In Orphism it is both temporal and spatial, as the wheel of life through the seasons is governed by the circular movement of the stars. The Orphic reformation of the Dionysian religion involves worship of the heavenly bodies – especially the Sun – as measurements of time.

Orpheus, as a cult myth, represents, according to Seaford, ‘the victory of unity over fragmentation in both cosmos and self.’ The oppositions expressed in mystery cult – between limited and unlimited, individual and community, fragmentation and wholeness – may provide, he speculates, a ‘traditional model’ for the oppositions in money, as unconsciously projected by the philosophers.

The idea of experiencing the wholeness of self in the presence of the One through mystic initiation occurs in Plato’s Symposium, where the priestess Diotima says that beauty is revealed to the initiated as distinct from all things that partake of it, and as unchanged by their passing in and out of being.

This may suggest, according to Seaford, that “The mystic notion of a concealed fundamental truth may be adapted to – or even stipulate – the new cosmological idea (however counter-intuitive) of a concealed impersonal reality underlying appearances’; and that ‘the transcendent mystic object is unconsciously fused with the transcendence of monetary value.’

Plato, despite his anti-materialist outlook, approves of money because it renders things homogeneous and commensurable. The Guardians in Plato’s Republic, who have gold and silver in their souls, and are free from ‘the polluting human currency of the majority.’ In this way, Seaford says,

‘Plato’s divine precious metal combines its traditional immortality with the socially constructed, necessarily unchanging, impersonal and invisible value of coined precious metal, located in the soul…’

The absorption of individual things into their ideal unity consists of sublimated monetary value, which becomes the source of ‘being beyond being’. Thought autonomously acting on thought is imagined as in a way which resembles money producing interest in likeness to itself. Aristotle says that interest is an ‘unnatural; mode of acquisition because, as production of like-by-like, it transgresses the ‘natural; role of currency as means for exchange and circulation of wealth. The unlimited monetized power of the tyrants is condemned by Aristotle, who says that the free man ruling over his oikos is only self-sufficient to the extent that he is part of the self-sufficient polis. For unity to prevail in the face of the unlimited power of money and greed the polis must limit itself in terms of its size, population and class inequalities.

Seaford describes how in Greek tragedy the transcendent power of money to efface all customary distinctions converges with the ancient unifying power of mystery cult and communal reciprocity. The struggle between unity and fragmentation can be seen in Euripides’ play The Bacchae. The tyrant Pentheus is hostile to the Dionysian mystery cult and plots to expose its secrets by means of bribery. The god Dionysius, disguised as a man, tricks Pentheus into disguising himself as a woman to spy on the cult and then arranges to have him discovered and torn to pieces by crazed Maenads.

Of the blending and clash of opposites Seaford comments, ‘In Pentheus, as in the vision of Parmenides, the self-sufficiency of the man of money combines with the isolation of the mystic initiand.’

Monetization marginalizes communal reciprocity and actualises the illusory individual autonomy of the tyrant who like, nobles in general, depends in reality on the socially constructed acceptance of the value of money and its power to circulate beyond the control of any individual.

References

Richard Seaford, Money and the early Greek Mind: Homer, Tragedy, and Philosophy (Cambridge, UK; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-521-83228-4

Walter F Otto, “The Meaning of the Eleusinian Mysteries,” The Meaning of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Frances Cornford, From Religion to Philosophy (Princeton Paperbacks: 1991)

Alfred Sohn-Rethel, Intellectual and Manual Labour: A Critique of Epistemology.