Growing up in the Lost World of the World's First Railway Station

From Railway Kings to King Mobbers

Dave and Stuart Wise, whose writings I have the honour and pleasure of publishing at B.P.C books , founded King Mob in the 1960s with the English Situationists, and just kept on going, fighting the Spectacle. So what do they have to do with the 19th century railway boom that charged up the industrial development of globalised capitalism? As we shall see, quite a lot.

First a bit of industrial history…

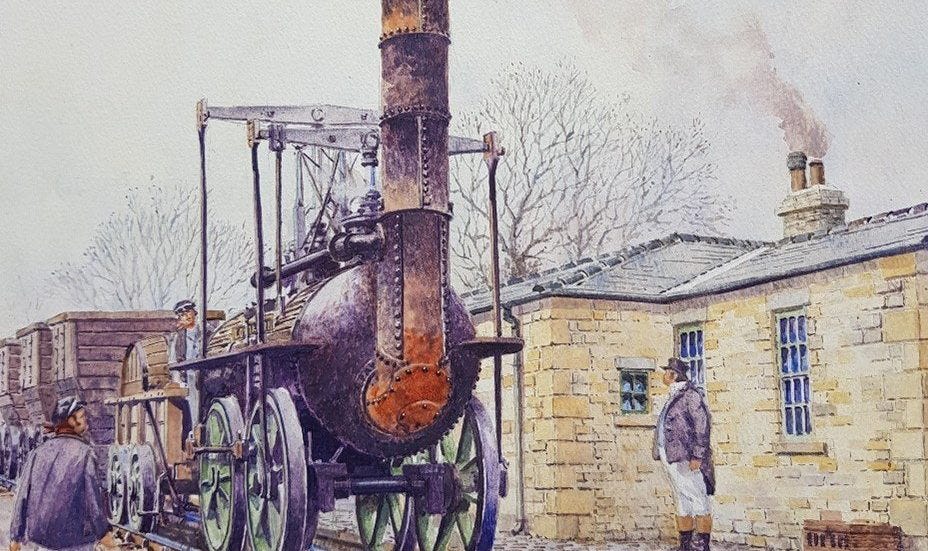

On 27 September 1825, the Stockton and Darlington company’s first engine, Locomotion No. 1, built at George Stephenson’s works in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was hauled by horses to Heighington, in Newton Aycliffe, County Durham and placed on the line. It then puffed its way into history on a 26-mile journey to Darlington. In 1826 Heighington began to develop as a collection point for goods and parcels transported by rail. A station was built there by the railway company in recognition of the fact that users of the railway and its adjacent depot needed shelter and refreshments when waiting for trains. It is now recognised as being the earliest railway station in the world.

The station was downgraded in the 1970s to an unstaffed halt. The station building then became an inn, named Locomotion No. 1, but this closed in 2017. Since then the building has become dilapidated and subjected to vandalism. It is now on Historic England’s Heritage At Risk Register. The Friends of the Stockton and Darlington Railway aim to purchase the property with funding from the Community Ownership Fund, National Lottery Heritage Fund, and e;sewhere. The Friends want to restore the buildings to reflect their origins as an early station and inn.

Growing up in the Lost World of the World’s First Railway Station

Dave Wise

The Wise Twins - David, who writes the following, and Stuart, who died in 2021 – were born in 1943 in a wartime health clinic in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Mrs Wise’s stay was paid for by the Daily Mirror; whose reporter, having learned that the baby twins were going to be of record size, knew it was a good human-interest story. The Wise family then moved to County Durham and lived for several years in a cottage adjacent to Heighington Railway Station, which itself represents another record: of being the first railway station in the world. (ed.)

From 1943 until the beginning of the 195Os our family lived in the cottages adjacent to Heighington Station.

More cottages (now disgracefully demolished) were built on-site in the late 19th century to house railway workers. All the workers' families who resided here were left wing. Most belonged to, or had affinities with, the old Independent Labour Party of Kier Hardie and his ilk, who were in their heyday, before the onset of World War One. There was one exception: the signalman Fred Sturdy, who was a member of the Communist party. Fred was a bit paranoid as he was always getting attacked for his belief in Russian 'communism', though not from a right wing perspective but from a more sophisticated ILP perspective which pointed out that the revolution in Russia was a failure and Lenin's victory merely a coup d'etat. However, all this disagreement with Fred was done in a witty rather than a nasty put-down way. Thus when the seasonal autumnal - often huge - murmurations of starlings from Siberia arrived on the Durham coastal flatlands of which Heighington was part of, neighbours would joust to Fred commenting that "Stalin's arrived".

Of course, these comments must be seen in the historical context of a general fear stoked up by the USA after World War Two: that Western Europe was about to fall to large Communist parties in Italy, Belgium and especially, France. Fred had a tricolour flying in his backyard ( historically the tricolour had been flown especially in areas of northern England - as against the union jack - in the long aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789). Fred suggested that if the party took over in France, then, considering the country's rebel history, a real grass roots, liberatory revolution might be instigated which would then spread over the rest of Western Europe. Nonetheless Fred often felt paranoid and lonely; on a Friday night would get rotten drunk in the nearest pub - well over a mile away in Aycliffe village - then stumble back home down an unlit dark tarmacked road which ended in his backyard situated just below our bedroom window. He then would throw up for a considerable time shouting "I wanna die, I wanna die". waking all of us up as we broke out into uncontrollable laughter tempered with sympathy for our fine neighbour! After all, we knew from a young age that signalmen often developed acute psychological problems due to isolation in their cabins, working in highly responsible positions. Indeed, around the same time a signalman who lived in Aycliffe village and worked on the main line from London to Edinburgh - and whom we knew through parents - committed suicide because he was held responsible for a few coal wagon derailments that delayed the Flying Scotsman for a few hours...

More or less, the atmosphere in these cottages was very friendly and neighbourly. Rarely were there any disputes (actually I cannot remember anything really serious). Tramps were welcomed, given money and food together. The charity came with a dollop of Wesleyan trade union Methodism, even though the churches and chapels were too far away for any Sunday attendance and no one had a car. At Christmas, New Year and other holiday there were get-togethers - often quite large. I look back on them with delight; even as a child I often found the conversations intriguing as engine drivers mulled over difficult sections of local rail track they had to navigate, as well as train crashes, and more general takes on society at large.

This of course was the time of Prime Minister Clement Atlee's Labour government, which in retrospect perhaps the most progressive government these islands ever had, even though there wasn't much of a visceral attack on Tories, but rather a voice of progressive optimism about the future. Thus comments sometimes were pointedly directed towards us such as: "Hey lads when you are grown up, you won't have to worry so much about money as transport will be free and rents reduced to next to nothing." Such comments struck home though in a mild way as somehow or another we'd already felt such 'truths' in our bones.

Moreover, there is another interesting aside to all this: the formation of "Landscapes of Contempt". The original rural landscape around Heighington Station had over the past decades been turned over into factories. Come the Second World War they were requisitioned by the State for the assembly-line production of military shells and bombs. The buildings, both high and low, were then covered with soil and planted with all kinds of scrubland vegetation, particularly gorse, and were interspersed with ponds. From above It would have looked like a veritable wilderness, so the high flying Luftwaffe raider were never able to identify a target. At this same time women workers - referred to as "The Aycliffe Angels" - were recruited to make the shells arriving each morning at Heighington Station from Darlington, Bishop Auckland and elsewhere. Little did they realize that the chemicals they were using were often toxic and even lethal enough – as was discovered later - to cause cancers.

Another aside: as babies our double-hooded pram was often left outside unattended on the public thoroughfare. The Aycliffe Angels returning home from their long daily stints in the ammunition factories would pass us by as they approached the station platforms. Delighted to see us, they would times linger around our pram giggling playfully. Knowing we were twins - though not knowing our parents - they assumed we were different sexes as we seemed to act differently - with Stuart identified as male and myself as female. Then some of the Aycliffe Angels decided to treat us. They bought Stuart a large teddy bear, and me a prettily dressed doll in a skirt! In fact "our Mam" had desperately hoped while pregnant that she'd be giving birth to young gals but alas nothing of the sort. When we started growing up the teddy bear and doll remained in the cluttered corner of the living room next to the abandoned pram.

Maybe I was about 3 or 4 before I became cognisant of what had happened. The doll wasn't passed onto a charity but remained uselessly abandoned. And then around 5 years old I pulled the doll's head off leaving it beside its former plastic body. I have no idea why I did such a thing but there they lay side by side as further years rolled by. Then, years later when I was in the first year at art school and I decided to do a six foot by six foot painting - oil on canvas - of the doll with its head off lying next to its former body surrounded by something of a mini jungle of broken childhood toys. I have no idea why I decided to do such a painting; was it a personalized Salvador Dali even though - for some reason - it had the title of "Tribute to Hugh Gaitskell", mirroring a Labour party I was about to abandon forever? All I know it was thrown into a large attic of 13, Eslington Terrece, Jesmond, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne which was already full of junk from previous decades of tenants. And there it possibly remains.

As children we often joined in with the kids of other railway workers in some pretty wild behaviour: knocking things down, like the abandoned water pumps we weren't supposed to touch, or setting fire to railway embankments or platelayers huts covered in tar. All for the hell of it. We also built dens everywhere such as in trees but especially across the 'infamous' beck that flowed underneath part of Heighington Station - called Demons Beck, part of the shadowy, ghostly folklore of the area that still managed to scare the locals.

The 1940s was a time of reflux; when a traditional working class was beginning to lose its identity or at least was morphing. Old poverties still remained but mass consumerism was just in the wings and the TV set had yet to make its deadly incursions. Small working class communities like ours were relatively common but there was little notion of the "new poverties" on the horizon plus the deadly isolationism that would go with it, never mind the reality of an extinction apocalypse as nature was torn to shreds.

The joys of the local natural life have lasted in our memories: the corncrakes that could be regularly heard on the other side of the railway from our bedroom window, and the flying nightjar in the evenings at the back of the house in neighbouring fields. Many of the railway workers who inhabited these cottages were also nature-sensitive, memorably revealing to us hare's nests (known as forms) hidden among long grass. In this playground we rapidly acquired a quite amazing knowledge of nature starting off with the newts in the industrially refashioned ponds which were home not only to the common Smooth Newt but of all things, a large amount of Great Crested Newts. Our long journey into eco-activism was thus begun..

David Wise: December 2023, plus editorial input from David Black, May/June 2025