Fractured Urbanism: Metro-Land, Empire-Land and the Council of Brent

A Short Dérive in Space and Time

“Wembley illustrates a state of affairs which, starting from the local, reaches the global aspirations of governments both from yesteryear and of today for the means and mechanisms of production and domination.”

This week’s guest poster, Peter Baxter, is inspired by last week’s contribution from David Wise, the co-founder in the late-1960s of King Mob, who were associated with the Situationists. Wise, a true innovator of radical praxis generally, was, along with his twin brother, Stewart, a pioneer of guerrilla gardening:

‘We… turned our attention to scruffy, gloriously weed-ridden public space with the intention of vastly increasing their inherent bio-diversity. We never asked permission of the powers that be - usually town councils - because we knew we'd be told to fuck off for not possessing requisite qualifications, etc. Constantly under attack from officialdom and the police we nevertheless over the years produced some remarkable spaces which even moronic bureaucrats had to grudgingly admit was the case… our eco interventions over the last few years on Wormwood Scrubs in west London were somewhat simultaneously explained by ourselves through placards, bird boxes and the like hung high up in trees - many around the subject of ‘suicide capitalism’, which was basically an ecological concept elucidated by Jaime Semprun.’

Peter Baxter writes:

Guerrilla gardening – the term used to describe the cultivating of plants in the soft verges of public spaces (‘common land’) – is practiced by people who want to improve their local environment (and also to keep fit). Strictly speaking, local council officers should always try to facilitate control of the commons. Dave Wise, in his anecdote of doing something (dis)similar, says he 'never asked permission of the powers that be - usually town councils - because we knew we'd be told to fuck off for not possessing requisite qualifications, etc'. This seems to fit with King Mob’s quote from Karl Marx: 'I am nothing but I must be everything.' According to Marx in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right (1843):

‘The link of state office and individual, this objective bond between the knowledge of civil society and the knowledge of the state, in other words the examination, is nothing but the bureaucratic baptism of knowledge, the official recognition of the transubstantiation of profane into holy knowledge (it goes without saying that in the case of every examination the examiner knows all).’

Not every council officer does facilitate control of the commons, and those that don't succeed in perpetuating the bureaucratic baptism of knowledge, often by not being examined but becoming examiner.

Wise’s article took me to Alèssi Dell'Umbria’s Full Metal Yellow Jacket, which I thoroughly enjoyed and made me rethink the basic stuff of ‘doing’. The therapeutic aspect of revolt is also what makes it so politically powerful. In Dell'Umbria’s gloss on Marx (on Hegel), he writes:

‘A [political] party [...] proves itself to be the winning party by splitting itself into two parties: it thus shows that it contains within itself the principle it has previously opposed in an external way, and thereby sheds the one-sidedness from which it arose.’

The innate ineffectiveness of the modern political part can be seen in contemporary populism, Dell’Umbria writes:

‘Populism consists in pandering to the affects produced by this world and maintaining them as something positive, whereas a revolutionary attitude places its trust in a future that gives birth to new forms of political sensitivity throughout the course of the struggle. Let’s never lose sight of the fact that the negative is the driving force behind any movement. In fact, in all these rebel camps that are multiplying throughout the world, the transcendent figure of the people gives way to the immanence of the common.’

Dell'Umbria's use of the peripheral in reference to the central business districts of Paris in his article helps us to think through the geographic, historical and political aspect of being an officer in 'one of Britain's most diverse boroughs' - Brent, west London. Seen from its own perspective, it is full of lively communities and has a rich cultural life. Split geographically by the ring road around Central London, the North Circular Road - that horizontal chimney of noise and nitrogen dioxide pollution - it is also split historically and politically by the people who live in Willesden in the south and Wembley in the north; who have in both cases come from all over the world to make a home. One is most likely to die of phthisis in the south as HGVs head centrally from the junctions. Its local history over the last 150 years is suburban and anecdotal, rural and folkloric, aristocratic. subaltern and poor; thus creating perfect contradictory conditions for humanity to be together cheek by jowl.

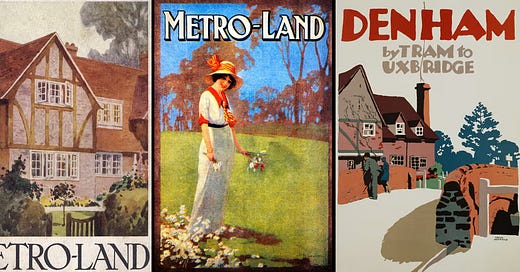

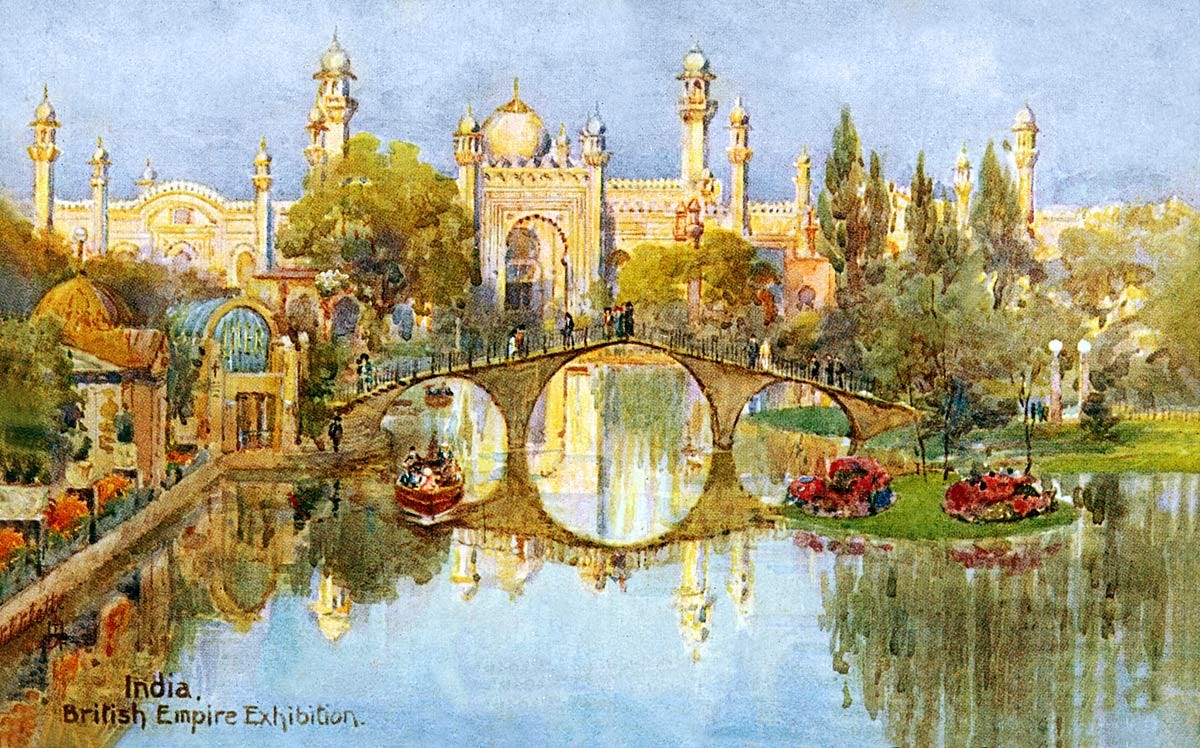

Wembley Stadium sits smack-bang in the centre of the borough, which once marked the borderland between the London suburbs of Kilburn and Camden, and the British countryside. At the start of its urban growth in the early 1900s with Metro-land (named after the then-new Metropolitan Railway), and Empire-land (named after the Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924), its peripheralisation to the capital made it central to the British Empire. Mediated by the grand Empire Exhibition, the marriage of business and government adorned the landscape with pavilions and palaces to showcase the properties of industry, commerce, culture, trade and leisure; with distractions of fun and extravaganza.

A chance for Empire to bounce back from 'The Great War', the Empire Exhibition moment espoused the depolarisation of class and race by masking its opposite. Wembley ‘welcomed the world’ - not. In the configuration of capitalism between the peripheral/provincial/colonial and the capital/centre/government it expressed the hierarchical organisation of the British Empire: hub and spoke, toil and choke. Wembley illustrates a state of affairs which, starting from the local, reaches the global aspirations of governments both from yesteryear and today for the means and mechanisms of production and domination. Local and national government maintain the Wembley estate as private property and, even more misguidely, as something positive.