Dynamite Dilemmas: Black Ops in the 19th Century

British intelliegence, the Fenians, and the Undoing of Charles Parnell.

This review was published in Notes From the Borderland in 2002

Dynamite Dilemmas

David Black

Fenian Fire – The Government Plot to Assassinate Queen Victoria. Harper/Collins

Land Wars

Christy Campbell’s book is a ‘forensic historical’ investigation into the ‘Jubilee Plot’ of 1887. The book’s sub-title is, or course, publishers’ hyperbole - at no stage did anyone in the ‘government’ say anything like ‘let’s blow up the Queen’. The ‘Plot’, as Campbell describes it, was ‘a “blood-curdling” scare cooked up by a counter-intelligence operation which had gone to war on itself’; a ‘political conspiracy’ that went all the way up through Sir William Pauncefort, head of Foreign Office Secret Service, to the Tory Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury.

The year 1858 saw the founding of the Fenian Brotherhood (FB) in New York and the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood (IRB) in Dublin. Fenians fought on both sides in the US Civil War and as soon as it ended, many of them headed for Ireland and took part in an abortive coup in Dublin, in 1865. Others joined the unsuccessful Fenian invasions of Canada (1866 and 1871). But it was only when the Irish masses themselves mobilised that the spectre of revolution was raised. In 1879, the Irish Land League’s rent strikes and ‘boycotts’ rendered the landlord system almost unworkable. The land campaign was inspired by Michael Davitt, some-time gun-runner, political prisoner, revolutionary intellectual and mole-hunting author of ‘Notes of an Amateur Detective’. The campaign and was backed by Charles Parnell, whose Irish Party had over 70 MPs in the House of Commons and effectively held the balance of power. Parnell thus found himself in a position to do a deal on Home Rule with the Liberals, who respected him as a ‘constitutionalist’ and moderating counterweight to the ‘men of violence’.

Parnell, however, according to Davitt, knew ‘in his heart’, that Ireland would have to take up arms, sooner or later, even if he wouldn’t say so in public. As a compromise Davitt called for a ‘New Departure’, which would give Parnell a chance to achieve an Irish parliament as a first step to full independence. When Davitt toured the USA to raise funds for the Land League he attempted to dissuade Fenians from carrying out any military actions that might undermine Parnell’s negotiations.

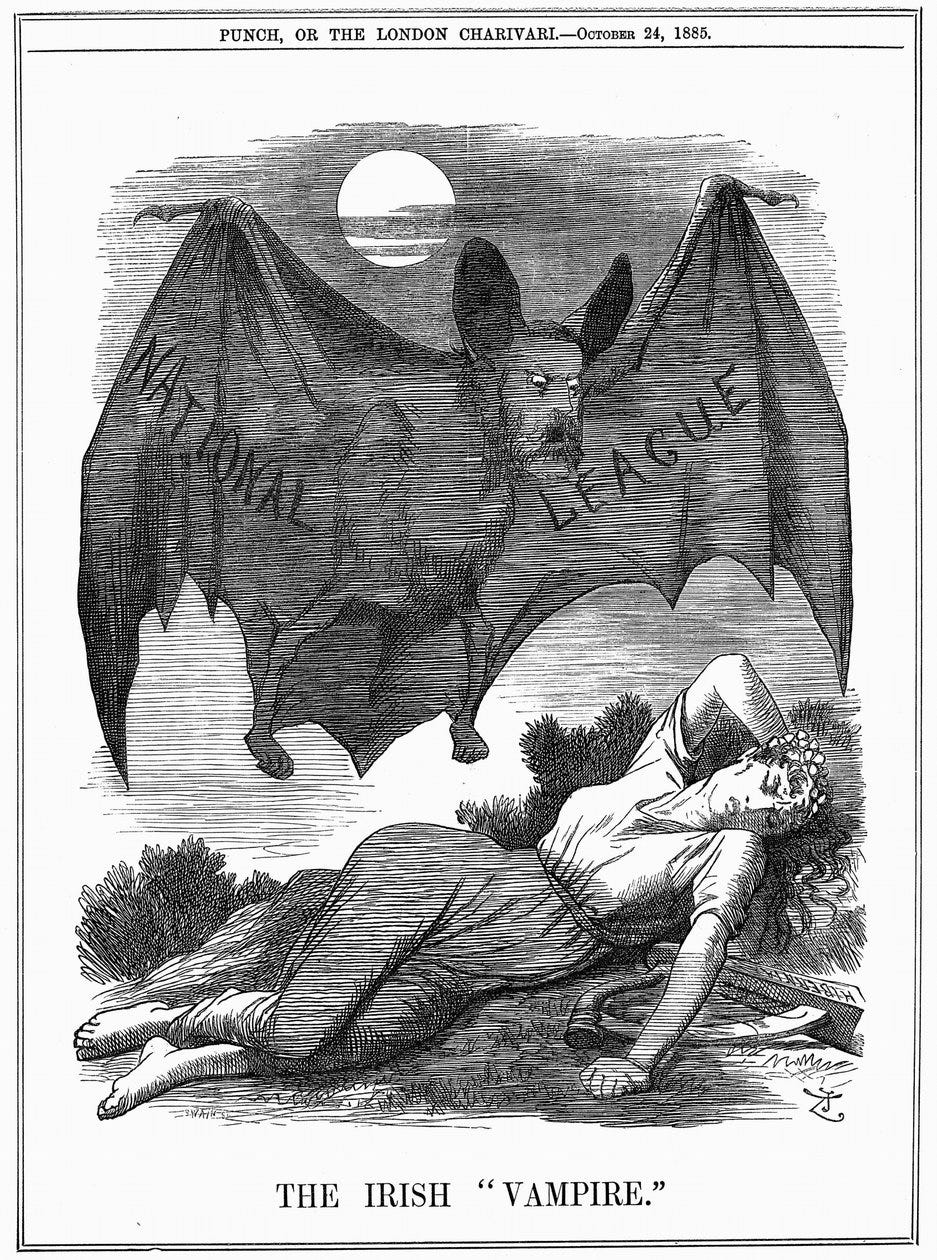

Ever since the IRB bombing of London’s Clerkenwell Prison in 1866, which massacred a large number of civilians, the press had made the ‘Irish bomber’ the most feared and most caricatured figure in Imperial demonology.

The ‘intransigents’ of the Clan-na-Gael under the leadership of O’Donovan Rossa had no time for the ‘New Direction’. In 1880, he sent ‘missioners’ to England to renew the bombing campaign.

Dynamite

In March 1881, the modern age of terrorism was inaugurated in St. Petersburg. A dynamite device was thrown by a Narodnik revolutionary into the carriage of Czar Alexander II, blowing him to smithereens. This ‘spectacular’ outrage sent shivers through the palaces of power in London and Dublin; for it was known that the Irish rebels had been experimenting with their own dynamite-delivery systems.

With activity in the Irish countryside reaching a ‘near revolutionary scale’ in 1881, the Liberals banned the Land League and imprisoned Davitt along with several Irish MPs, including Parnell. In May 1882, the Secretary for Ireland, Lord Cavendish and his civil servant Thomas Burke were stabbed to death in Dublin’s Phoenix Park by a group called the ‘Invincibles’. Parnell, who had been released along with Davitt and his MPs just prior to the incident, condemned the killings and wound up the Land League in order to enter into secret negotiations with Gladstone and the Liberals. The go-between in the talks, Parnell’s secret lover, Kathy O’Shea, was the wife of Captain William O’Shea, a ‘bag carrier’ for Liberal MP, Joseph Chamberlain. As the Liberals were split on the Home Rule question the negations never got off the ground. In 1885 Parnell’s MPs voted to bring down the Liberals, thinking they might get a deal from Salisbury’s Tories.

The Spymaster

Scotland Yard, headed by James Monro was hostile to Parnell. Monro’s chied Fenian-fighter at CID had an informant in Clan-na-Gael(Thomas Beach) who reported that Parnell had met the Clan’s military leadership and was secretly committed to armed struggle. But to Home Office ‘spymaster’, Sir Edward Jenkinson, this double-dealing was to be tolerated because he believed that Parnell was the key to a solution of the ‘Irish Problem’ and that the secret state needed to properly ‘control’ the dynamiters in order to bring about a settlement. Jenkinson persuaded the Home Office to grant him ‘overall control’ of intelligence on Irish rebels at the secretive ‘Room 56’ in Whitehall. The Met were alarmed by his growing power, for Jenkinsons’ own methods were as much crime-creating as crime-solving. And some of them were being exposed to the public gaze. Another spy of his in the Clan-na-Gael, Jim McDermott, recruited a team of dynamiters in Cork and Liverpool and arranged to have them caught red-handed. But when McDermott tried to set up Davitt, the intended victim worked out the spy’s game plan and warned Rossa. McDermott barely escaped an assassination attempt on his return and had to go into hiding.

In 1884 Jenkinson sent Captain Darnley Stephens to Paris bearing a letter of introduction from a Parnellite MP. Stephens met Patrick Casey, a known dynamiter, and Eugene Davis, Rossa’s main agent in Paris. Together they dreamed up plots to attack British royalty. Within days Stephens was back in London and details of the ‘plots’ were splashed all over the newspapers. Next, Stephens brought Casey to London and took him to the House of Commons, where they tried and failed to get a Parnellite MPs to assist in a jailbreak plot they had cooked up. Monro’s CID men looked on, noting that one of the ‘Spymaster’s’ officers was stirring up mischief in the Mother of Parliaments with a known dynamiter in tow. What Monro didn’t know was that the Stephens-Casey drinking club in Paris harboured another one of Jenkinsons’ spies, Patrick Hayes.

In late-1884, Casey informed Jenkinson of an impending attack on Parliament. Jenkinson dutifully passed a warning to Scotland Yard, urging Monro to ‘step up security’. But at this time, Monro’s detectives were at full stretch, trying to cope with a Christmas bombing campaign directed at London Underground. Monro desperately wanted more information on the plot from Jenkinson, but it was not forthcoming.

Sure enough, on 24 January 1885 two bombs went off at the Commons and injured a policeman. Monro fumed. Whatever next?

In the short term, not a lot. By 1886 the bombings had stopped and the Clan had secretly decided to give Parnell another chance. Jenkinson informed opposition leader Gladstone of the new becalmed climate of terrorist opinion, but also warned that without a deal with Parnell, ‘the outrages and murders of 1882 would be repeated… dynamite explosions – the murder of statesmen and officials, all are determined and preparing for it’. Failure, he added alarmingly would ‘probably lead to the disintegration of the Empire’.

Jenkinson wanted Parnell to stop ‘denying all knowledge of the dynamiters’ and instead, ‘boldly’ show his ‘connection with them, showing their strength and at the same time, saying he disapproved of their methods.’

The Unionist Trap

When Gladstone told Queen Victoria of his Home Rule plan, Her Majesty - who had become rather paranoid about Fenian dynamiters and rebellious peasants - was horrified. So were the Unionists, including the Unionist Liberals led by Joseph Chamberlain.

For some, the time had come for concerted covert action to stop Home Rule. A ‘black propaganda’ organisation was formed, consisting of journalists, MPs and spies – all presided over by the Times newspaper, which began running anti-Parnell stories based on what the ‘team’ came up with. Richard Pigot, a muckraking journalist and forger, in the pay of the ‘Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union’, claimed that he could obtain letters - proving that Parnell had secretly supported the Phoenix Park murders in 1882 of Lord Cavendish and Thomas Burke. The ‘black bag’ of letters was obtained by Foreign Office spy, Casey.

In July 1886, Gladstone lost the General Election and Salisbury returned to power. By this time Monro, who had regained control of operations in London, had discovered that Jenkinson was running a semi-criminal army of stool pigeons based in a Soho boarding house. Monro rolled up the whole network and prosecuted Jenkinson’s main tout for bigamy. Worse still for Jenkinson, his sacked assistant, Darnley Stephens, took his revenge by telling the new Tory cabinet that Jenkinson knew all about the ‘black bag’ letters but had chosen to suppress them. Jenkinson was forced to resign and Monro was put in charge of all CID and secret Irish work on the mainland.

The ouster of Jenkinson meant he was no longer masterminding the ‘Jubilee Plot’. That role now passed to Charles Carrol-Tevis: ex-Union Army General and former adjutant-general of the IRB military operations, who was the British Foreign Office infiltrator of the Fenians in Paris. What linked Carrol-Tevis to the higher echelons of the British state was his close working relationship with Captain O’Shea, whose wife, Kitty, was actually Parnell’s secret lover.

Jubilee Jitters

In 1887 – Jubilee Year – the Times ran a ferocious campaign against Parnell based on ’inside’ information from the ‘black bag’ team, warning that there were some ‘pyrotechnics’ afoot to ‘disrupt’ the Queen’s Jubilee. And the man who seemed to be trying to organise them in New York and Paris, was another one of Jenkinson’s spies, who had been a ‘friend’ of the Foreign Office for nearly 20 years: General Frances Millen, of the Clan-na-Gael.

Millen, a former British soldier who served in the Crimea, fought in Mexico for Benito Juarez against Emperor Maximilian and achieved the rank of general. After joining the Brotherhood, he was been appointed by John O’Mahony as “(Provisional) Chief Organiser” and then worked for John Devoy and Alexander Sullivan in the Clan. Millen’s ‘talent’ lay in plotting grandiose military adventures on a global scale and at great expense. He had tried to get Spanish support for the storming of Gibraltar by an ‘Irish Liberation Army’; he had promised the Venezuelan president legions of Fenians if he would invade British Honduras; and he had conspired to get the Russians to sponsor Fenian invasions of the Cape and British held-Afghanistan. He was also a confidant of Captain O’Shea.

Early on 1887, Millen travelled from Paris to London and introduced his two Fenian daughters to Parnellite MP, Joseph Nolan. In July Nolan took them on a tour of both Houses of Parliament. Monro, of the CID had agents watching the general and his friends in Paris, thought it might be a reconnaissance job for an updated Gunpowder Plot.

A month before the Jubilee a team of Fenian bombers was despatched from New York. Although they botched the travel arrangements and arrived in London too late for the big day, they decided to stick around and do some ‘pyrotechnics’ with their load of dynamite. Monro picked up their trail. He knew that Millen had also been conspiring to introduce the bombers to some of Parnell’s parliamentarians. Monro’s detectives also uncovered a stash of dynamite in a house in Islington and caught two of the bombers. Millen, however managed to high-tail it back to Paris, and most of bombers escaped back to the US

The Undoing of Charles Parnell

The Times’ ‘black big’ job on the Liberal-Irish alliance had been instigated by Prime Minister Lord Salisbury himself. With questions being raised in the House, a Parliamentary Commission was set up with full legal powers. But for Salisbury this was no defensive measure: it allowed the Times’ lawyers to act, in effect, as prosecutors of the Parnellite MPs, who were arraigned before the Commission one by one; and of Davitt, who was serving as Parnell’s intelligence officer. Davitt’s problem was that he had met Millen on Clan business in Dublin in 1879 and any appearance by the General on the Times ‘ behalf might caused him some trouble. At this point Davitt went to Paris for a meeting with his old adversary, Jenkinson, and made a deal. Jenkinson told Davitt everything he needed to know about Millen and in return Davitt agreed not to expose anything embarrassing about Room 56.

When Pigot was exposed by the defence as a forger, he absconded and committed suicide. For the Times, which was paying for the Commission’s investigations, the fight was becoming costly. Shipping American spies over to testify on the Times’ behalf would of course have ended their usefulness for the state and cost big sums in protection money. The defence, run by the Liberal’s top lawyers and primed by Davitt’s ‘amateur’ detective work, was extracting information that was embarrassing for the government. The Parnell camp now knew not only that Millen was the Mr Big of the Jubilee Plot, but also that he was a British agent – and the prosecution knew they knew. In the case of CID’s long-time agent, Thomas Beach, his testimony admitted that he was employed as ‘a tout for the Times’.

There were two other ‘witnesses’ in America who could have turned the case for the government provided the Times was prepared to pay up. One was Patrick Sheridan: price £20,000. He was implicated in the Phoenix murders and claimed to have documents connecting Parnell with the ‘Invincibles’. But because the prospective deal was mentioned in the Commission proceedings before he had decided to make the trip, it was reported in the American press, so Sheridan thought it best to save himself from Fenian revenge by passing details of all his dealings with FO/Times agents in the US to Davitt and the defence. Only Millen was left as a potential ‘smoking gun’ witness, but in April 1889, he died in New York, apparently of natural causes. His revolutionary reputation remained intact long enough to give him a funeral fit for a Fenian hero.

Campbell poses the question of why the Parnell side did not expose the Times’ efforts to enrich a Foreign Office agent who had ‘evidently plotted to blow up Queen Victoria’. It appears that Davitt was told ‘Don’t mention Millen’ by someone close to Clan boss Alexander Sullivan. Sullivan was at the time under investigation by the Clan for financial fraud. Sullivan had completely trusted Beach and Millen and defended them against all doubters. But Sullivan, who was determined to destroy Parnell politically, had enough power to destroy his Clan rivals physically. Sullivan’s men assassinated his main accuser, Patrick Cronin, in Chicago.

Although the Commission failed to destroy Parnell, the Times managed to do the job by finally exposing his adultery with Kitty O’Shea who had been Parnell’s go-between in secret negotions with Gladstone’s Liberals. The Liberals and Catholic Church deserted Parnell, his party split and he died a broken man in 1891. The prospect of an Ireland united under Home Rule died with him.