The following is from an article I published in the Ethical Record Vol. 112 No.7, July 2007.

Historians of the Left have pointed out that in France the bourgeoisie had to fight a violent revolutionary war to extirpate the old feudal order. Contrastingly, in England compromise was possible, because in the 17th century Cromwell’s Commonwealth and the Glorious Revolution against James II had already laid the foundations for civil (capitalist) society.

After the French Revolution, the English industrialists and the landowners feared the working class more than they feared each other. The Whig’s Reform Act of 1832 extended the electoral franchise to a good section of the middle class. But with still only 700,000 voters in a land of twenty-five million subjects, the working class - whose leaders had supported the Whigs’ Reform agitation - felt betrayed and disappointed.

Worse was to come: the radical press was persecuted; trade unionists were transported to Van Dieman’s Land; Ireland was terrorised by paramilitary police; and the New Poor Law of 1834 established the hated workhouse system. Discontent intensified in the late-1830s, when hothouse industrial development produced an economic crisis. In the North and Midlands workhouses were burned and the Poor Law commissioners subjected to hostile demonstrations and intimidation.

‘A Complete Subversion of the Existing World’

Bronterre James O’Brien (1804-64) was educated as a lawyer at Trinity College, Dublin. In 1829 he moved to London where he agitated for Parliamentary Reform in collaboration with Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, William Cobbett and Henry Hetherington. Radical journalism was effectively censored by the Stamp Tax, which was brought in to make periodicals containing news too expensive for working class readers. When Hetherington was imprisoned for refusing to pay the tax on his weekly paper, The Poor Man’s Guardian, O’Brien stepped in as editor. In 1837 O'Brien began publishing Bronterre's National Reformer, which featured essays rather than 'news items'.

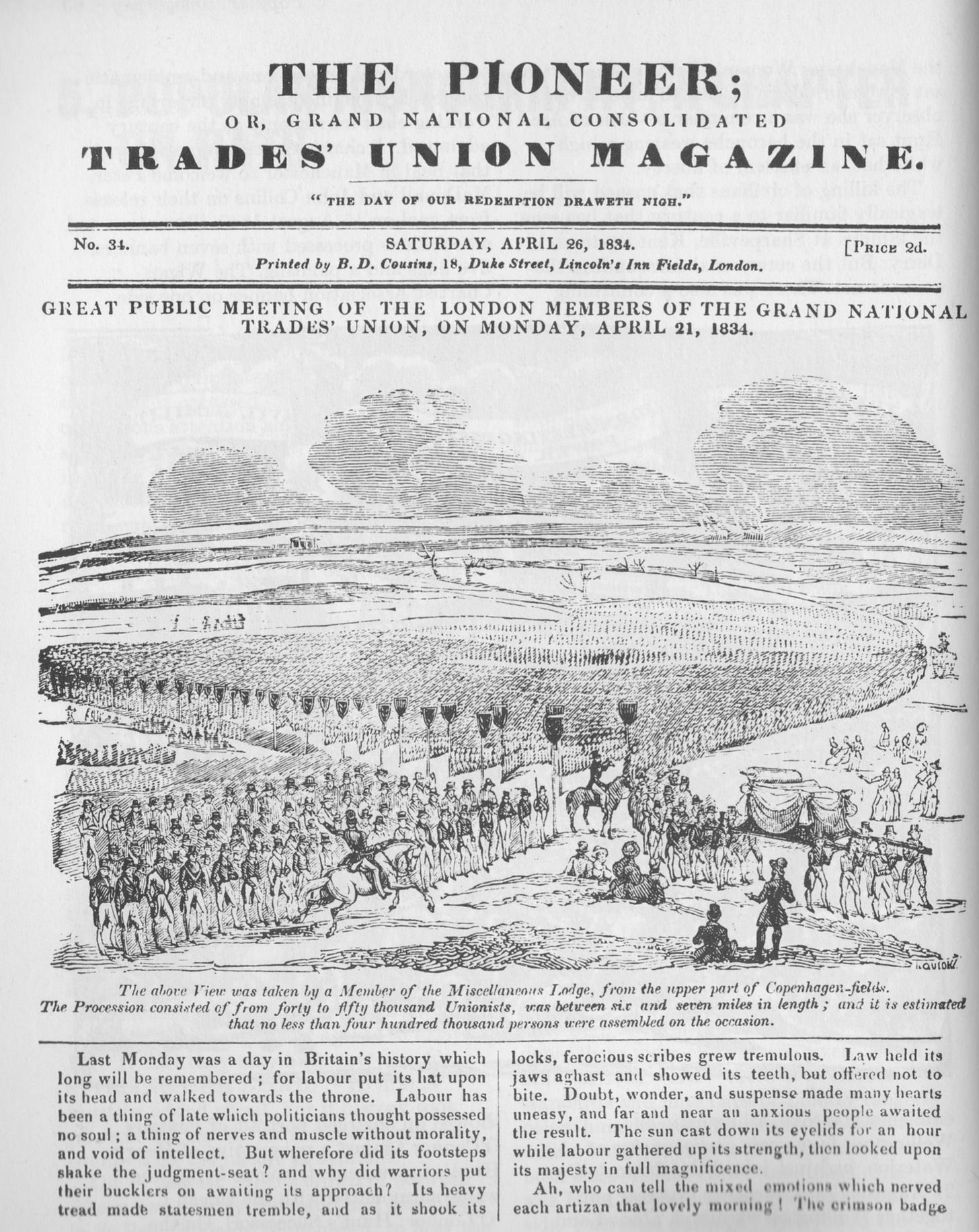

Initially, O’Brien was influenced by Robert Owen, the utopian socialist who led the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union, and founded The Pioneer magazine. O’Brien saw in Owenism a new idea for ‘a complete subversion of the existing world. The working classes aspire to be at the top instead of at the bottom of society – or, rather that there should be no bottom at all.’ But O’Brien was also an admirer of the French Jacobins, Robespierre and Babeuf, whose ideas, he thought, made up for Owen’s lack of historical understanding on the question of political power. In 1836 O’Brien translated Phillipe Buonarroti’s first hand account, Gracchus Babeuf and Conspiracy for Equality. Babeuf, executed by the Directory in 1797, had wanted the French Constitution of 1793 implemented and to fulfil what he saw as the logic of the revolutionary class struggle: economic equality and common ownership of property.

O’Brien saw the conduct of the Whigs in the Reform Crisis of 1832 as akin to the manoeuvres of the Girondists of the French Revolution: both had given political power to the ‘small middlemen... in order to more effectively keep down the working classes.’ O’Brien argued that the American and French Revolutions had left the ‘institutions of property’ intact, as ‘germs of social evil to ripen in the womb of time.’ The great democratic gains had been subverted by counter-revolution from ‘within and without.’ The next revolution therefore, had to be social as well as political: ‘from the laws of the few have the existing inequalities sprung; by the laws of the many they shall be destroyed.’

Chartism

In 1838 the six-point People Charter – essentially a program for universal male suffrage - was drawn up by leaders of the London Working Men’s Association and the Birmingham Political Union. Mass meetings throughout the kingdom elected Chartist delegates to a ‘National Convention,’ which was to meet in London in permanent session for the purpose of coordinating a petition campaign. Bronterre O’Brien was elected for west London to the Convention at a meeting in Westminster. Another Irishman elected was Feargus O’Connor, former MP for Cork, publisher of the enormously popular (and stamped) Northern Star newspaper, and leading agitator against the workhouses.

On 4 February 1839, the day of Queen Victoria’s opening of Parliament, the National Convention assembled at the British Coffee House, Cockspur Street, with fifty-five delegates. Robert Lowery, delegate from the north-east, recalled:

‘The British Coffee House being close by, those of us who had never seen her Majesty made a general rush to see her and her procession. Some of the gentlemen in waiting would have been astounded at the free criticisms and remarks made upon the beefeaters and paraphernalia of the procession.’

The moderates among the delegates argued that the Convention should just collect as many signatures as possible and present them as a petition to Parliament. O’Brien thought otherwise. As he had previously said in a speech:

‘I would remind you [of]the story of Gil Blas - where a famous beggar, who levied his blackmail under the name of charity, used to present his petition with one hand whilst the finger of the other was applied to the blunderbuss to assist the prayer of the petition. That was a style of petition that never failed.’

Also on the ‘Jacobin’ Left of the Convention was 20-year old George Julian Harney, who had absorbed Bronterre’s writings on the French Revolution and founded the London Democratic Association in the east end of London. The Left argued that, as there was no chance of the Liberal government taking any notice of the Petition, ulterior measures needed to be drawn up and enacted, including, ‘exclusive dealing’ ( a consumer boycott of exiseable commodities such alcohol, and of anti-Chartist shopkeepers), the arming of the masses (to defend their ‘constitutional rights’) and a ‘National Holiday’ (general strike). But first, O’Brien cautioned, they would need a lot more than the half-a-million signatures so far collected:

‘At present the Convention stands as mediator between the suffering people and the House of Commons... and it would be absurd to talk of ulterior measures unless we have two or three millions of signatures.’

People would only support ulterior measures if and when parliament rejected the petition. He likened the petition to a ‘notice to quit’; failure to obey the notice would bring about the ejection of the class enemy from the House of Commons. In large areas of the country huge demonstrations were taking place, and muskets and pikes were being procured. The National Convention, supported by thousands of contributions to its ‘National Rent,’ was sending lecturers to every corner of the kingdom. Female Chartist Associations were being formed, even though it had been decided by the male leadership that to demand the franchise for women would hold up the enfranchisement of men. In the face of all these developments the Convention moderates resigned.

Parliament’s Rejection of The Charter

In June of 1839 Parliament debated and rejected the petition for the Charter with very few dissensions. By this time the Metropolitan Police were arresting some of leaders of the movement for making allegedly seditious speeches, so a proposal was put forward to move the Convention out of London. Bronterre O’Brien agreed; it would be safer, he suggested, ‘under the guns of Manchester or Birmingham’ (both towns had extensive arms factories). The Convention moved to Birmingham. The day it opened, a massive riot erupted when police sent from London tried to stop speeches in the Bull Ring. This was followed by another big riot in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. At this time O’Brien was touring the country, giving speeches and he was indicted for making seditious speeches in Liverpool and Newcastle.

On 17 July the Convention finally voted to begin a month-long general strike on 12 August. But disagreements persisted. O’Connor and O’Brien favoured postponement. John Warden, a physical-force supporter from Bolton, reminded O’Connor that according to his own paper, the Northern Star, ‘the whole country was organised and armed to the teeth.’ O’Connor retorted,

‘There has never appeared in the columns of the Northern Star a declaration that the people were armed, but on the contrary a constant regret that the people were not armed.’

O’Brien cautioned that ‘if you strike universally, you strike successfully; but if partly unfavourably.’ The most serious question was how people would get to eat without a strike fund. The Convention settled for recommending 2 or 3-day ‘holiday’ with demonstrations and meetings throughout the country instead of a general strike.

With the failure of the strike plan, the National Convention lost credibility and in mid-September, delegates voted for dissolution. On its last day, Dr. John Taylor from Scotland moved a parting statement advocating ‘resistance’: ‘All constitutional law is at an end… brute force is now the order of the day,’ O’Brien described it as a ‘thoroughly illegal and dangerous document’; and in the end no statement was agreed on.

In the last days of the Convention, just when Monmouth delegate, John Frost, was telling the delegates that the people of south Wales were not prepared to strike, resolutions arrived from his ‘constituents’ calling for armed struggle as well as the strike. No sooner was the Convention wound up than a ‘Secret Council’ was formed by delegates favouring insurrectionary action.

O’Brien did not join them. With the collapse of the Convention, he had decided to withdraw from the movement. He explained later that he could not conscientiously take part in secret projects which would at best only produce partial outbreaks, which would easily be crushed and would lead to increased persecution of the Chartists. O’Brien believed that physical force ‘should have no part unless it began with the oppressor, in which case, the oppressed would be bound (by the constitution itself), to resort to physical force in self-defence.’

Insurrection

On November 3, 5,000 Chartist supporters in South Wales took up arms and marched on Newport, led by John Frost, who hoped against hope that it would have peaceful outcome. Elsewhere in the kingdom, members of the Secret Council had been preparing their own insurrections, notably in Newcastle, Carlisle, and the West Riding of Yorkshire. But when the news came through from Newport – 24 killed and fifty wounded by gunfire, and John Frost and his comrades arrested. the follow-up rebellions were hastily called off.

On 1 February 1840 death sentences passed on John Frost, Zephaniah Williams and Williams Jones were commuted to transportation for life. That same month, Bronterre O’Brien and Feargus O’Connor were tried by making seditious speeches. Their ‘moderate’ stance was not appreciated by the authorities, and they were sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment. So ended the first campaign of the Chartists. There two more (1842 and 1848) still to come.

{For further reading see 1839: The Chartist Insurrection, by David Black and Chris Ford, (Kindle edition)]

REMINDER - Sunday 18th May 2025

This year (2025) the Bronterre O’Brien Memorial Commemoration will be delivered by Professor Bruno Leipold, Fellow in Political Theory at the London School of Economics, and author of Citizen Marx: Republicanism and the Formation of Karl Marx's Social and Political Thought (Princeton University Press, 2024). This will be on Sunday 18th May 2025 - meet at 2.30pm for 3pm graveside talk at the Harriet Delph room in Abney Park Chapel for 3pm talk at Bronterre’s gravestone.

Abney Park Trust is celebrating radical writing with a year-long festival of book launches and author talks in the restored Abney Park Chapel’s Harriet Delph room.

Thanks! Typo corrected

Marvellous historical writing - thank you.

V. minor erratum: "1939".