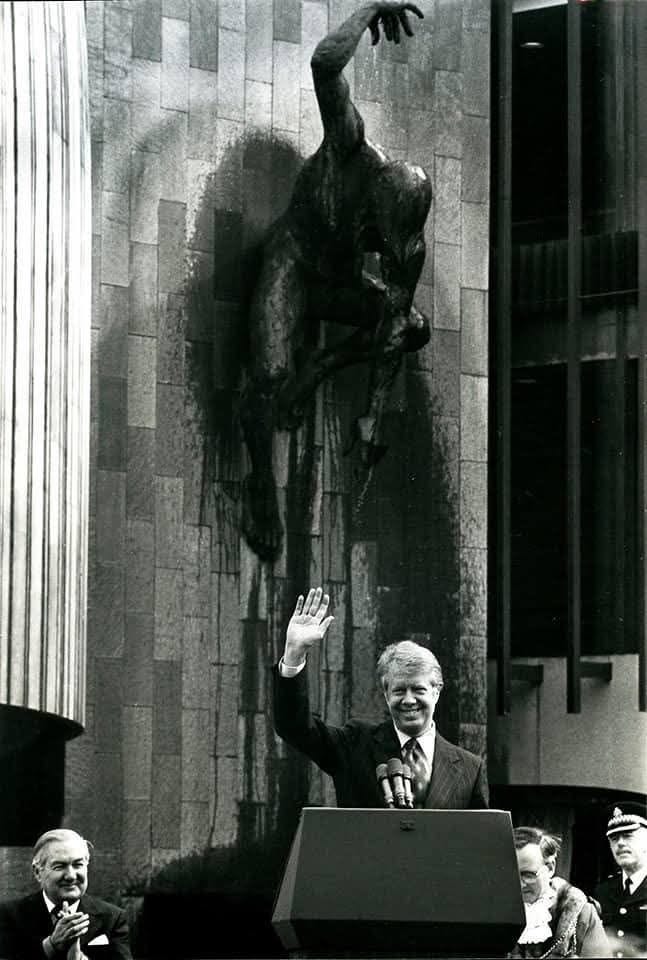

Another thing -as they say - that ‘couldn’t happen now’: Back in spring 1977 President Jimmy Carter was greeted outside Newcastle Civic Centre by 20,000 Geordies, who went crazy when he shouted ‘Howay the Lads’. And there were no armoured cars, helicopter gunships or rooftop snipers to be seen.

Carter was standing below the River God Tyne, a bronze statue installed in 1968 half-way up a high wall. The gravity-defying pagan deity looks like a Marvel comic book hero (swinging sculptor David Wynne was also famous for befriending the Beatles and hooking them up with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi).

The Civic Centre, designed by top architect, George Kenyon, was to be the dream palace – or ‘people’s palace’ if you will - of T Dan Smith, Trotskyist-trained leader of Labour-run Newcastle City Council. It was so long ago that the TV drama, Our Friends in the North, might have its audience believe that it’s portrayal of the corrupt Labourite politician of the 1960s says all there is to know about T Dan Smith, on whom the character is based. But T Dan’s real legacy is ambivalent, even tragic, as he really wanted to upend the British class-system, and eventually got stuffed - imprisoned for corruption - partly because his class enemies had it in for him, and partly because of his political naivety and illusions of infallibility

As a modernising urban planner T Dan Smith was responsible for a lot of demolitions in Newcastle, some of old buildings that weren’t missed, and others of buildings that were - and still are: replaced in some cases by hideous constructions, long demolished or persisting as eyesores. But the Civic Centre, with it’s ten nosey seahorses looking out across the landscape in all directions from the top of the tower, still kind of ‘shines’. As Alan Hull (of Lindisfarne) sang in Dan the Plan:

What went wrong with your city, the Brasilia of the North

Isn't it a pity, that no one knew it's worth

But the Civic Centre shines like money in your hand

Let's raise another glass to Dan the Plan

Chorus:

Oh Dan, you're a terrible man

Can't you see what you've done? you've spoiled all the fun

Oh Dan Dan... you killed me old man, you turned this house, into a caravan

You know it used to be mine, even the Fog on the Tyne

Now it's all snow and rain, am I wrong to complain ?

The following is an exclusive extract from the forthcoming book, Building For Babylon: Construction, Collectives and Craic, by Dave and Stuart Wise. This is the fifth title of the WiseBooks Series, which I edit for B.P.C. (publishing details forthcoming).

Seahorses

Although it could be said that Newcastle-upon-Tyne is an out of the way place, the city nonetheless has historically strived to achieve a major cultural image. City boss T. Dan Smith in the 1960s banally wanted the city to be, “A Florence of the north”. To even think you could build a “Florence” just like that and set aside from its essential historical time and place was a priceless piece of philistine and bureaucratic absurdity. With the demise of that nonsense Newcastle was to achieve a massive post-modernist impact by ironically ditching its grandiose Renaissance project by recuperating and turning into opposite that late 1960s life-enhancing experiment and more than embryonic subversion.

The city drew its sting, forcing most of the instigators into exile, proceeding to pave the way for a bankrupt modernity by massively promoting ‘end of culture’ culture in the forms of gigantic displays from the sculptor Antony Gormley’s moronic “Angel of the North” to the new waterfront Baltic Exchange Flour Mill, the veritable temple of Saatchi & Saatchi vacuity.

Have we also been guilty of glaring contradictions? Kind of, oh yes and all for dollario, dosh and spondoolies! During the early years of our magazine, Icteric, in the mid-1960s I was responsible for making a non-authored town planning monstrosity. In a way it was a precursor of the moment decade's later when skilled artisanal types were to do all the spade work for what were to become the neo-artistic masters of the universe.

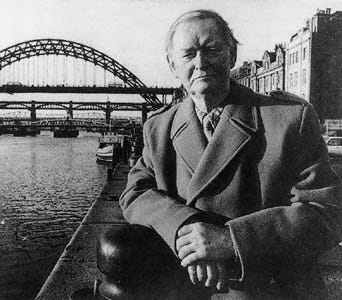

Way back then, John Murray McCheyne (1911–1982), master of sculpture at Newcastle University, was commissioned to design and produce (via hands that had touched Rodin's) an installation for the top of the tower of new Civic Centre, crowned by sculptures of ten seahorses. The idea behind the seahorses was to remind folks of Newcastle's proud past as a seaport. And ll for a mere £50,000 (half a million in today’s money). The Laing Art Gallery has McCheyne’s Family Group, 1959, in the manner of Henry Moore.

In 1966 I did a six-week course in Cornwall, where I honed my skills in building techniques, including plastering, woodwork, arc and electric welding, plus casting. McCheyne was under huge pressure to deliver on time the work he’d been commissioned for. He got to hear about my recently acquired skills and searched me out. If McChayne had heard of the Wise Twins’ frequent run-ins with the local Art establishment he certainly didn’t care, as he decided I was the “right man for the job.”

He offered me £500 in readies to build the Ten Seahorses in seven days! This was an unheard of amount of dosh for me in those days and being skint, young and fit I eagerly said "yes".

Grabbing a stash of speed I instantly set to work day and night in a workshop in the university, with an oxy-acetylene blower and piles of resin, clay, fibre glass, bronze and other metals, etc. I finished the job on time and sure enough the dosh was handed over to me immediately.

Though wrecked by speed and no sleep, I still had a thirst, so I headed for the local 'wild' Haymarket pub with its mixed clientele of hard working Geordies, though also home to the local beat poet scene plus blues joint. I opened the door and shouted out to all the punters, "the drinks are on me", and the punters that evening included Eric Burdon, Alan Price as well as Chas Chandler. After a few hours I was gloriously finished and staggered back to my broken down pad sleeping for about a week.

There's an extra interesting drift to this. Certainly our transcendence of musical orientation started in Newcastle in the mid 1960s somewhat spurred on by comments from Breton like "Let night fall on the orchestra" plus Rimbaud's "Knowing " (not 'great' as has been translated) "knowing music falls short of our desires." All of this was highlighted by our obsession with blues, jazz, especially bebop, the latter then reaching some kind of fascinating impasse moving beyond a musical terrain perhaps full of possibilities which we were slowly becoming aware of and all pointing towards a social revolution of unprecedented scope and fulfilment.

At the time I was friendly with Chas Chandler and we'd engage in quite passionate discussions roaming around such insights. I remember a particularly intense one on a cold snowy January midnight as I bumped into him on the middle of that great, desolate tract called the Town Moor right next to the city centre. This was before Chas 'discovered' Jimi Hendrix but in retrospect I often wonder how much he influenced Jimi especially the latter's penchant for the English guitar blues rock fallout as well as some aspects of English romantic poetry such as John Clare's decades long remorselessly unrequited love for Mary, "And the wind cried Mary".

I certainly remember discussing some of my own re-interpretations of romanticism with Chas Chandler and then you begin to reflect on underground connectivity ending up in unlikely places?? I now see there's a lot of stuff on the Internet about the possible connection between Hendrix and John Clare's lost love whom he became obsessed with for the rest of his tortured life. The most appropriate lines of John Clare's lines were as follows: 'But soft the wind comes from the sky / And whispers tales of Mary’ - Dave Wise, 2025

As someone from Newcastle, this was a really interesting read.