‘Another Language’ - Walt Whitman, Karl Marx and the British, 1850-56

Leaves of Grass and Revolution

'New forces and passions spring up in the bosom of society, forces and passions which feel themselves to be fettered by that society' (Karl Marx, Capital)

Resurgemus

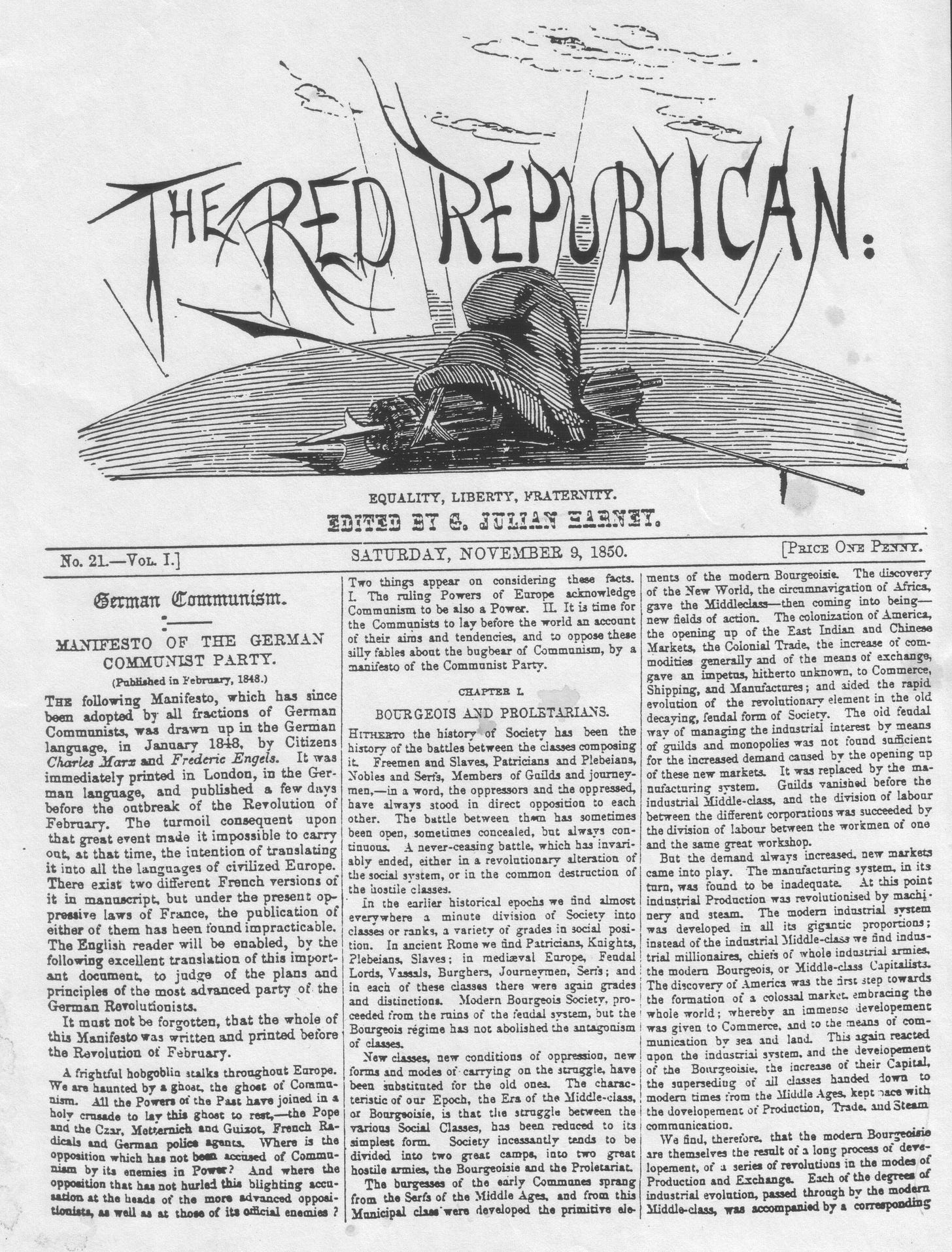

Walt Whitman’s name first appeared in Britain in the 3 August 1850 edition of the Red Republican, a weekly paper of the Chartist campaign for Universal Male Suffrage, edited in London by George Julian Harney. The published item was the poem, ‘Resurgemus’, which had appeared two months earlier in Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune. Harney’s weekly was the organ of the Fraternal Democrats, an organisation of European political exiles who had fled to England in the wake of the 1848-49 Revolutions. These included Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who had been banished from Germany, and Helen Macfarlane, a Scottish Chartist and Anti-Slavery campaigner who had fled the counter-revolution in Vienna of 1849. Macfarlane translated Marx’s Communist Manifesto for serialisation in Harney’s paper, and wrote articles und the pseudonym, ‘Howard Morton’. Uniquely, as a British radical, Helen Macfarlane’s writings express a familiarity with the philosophy of Hegel, and the works of the American Transcendalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Another contributor was the young poet and pagan critic of Christianity, Gerald Massey.

Historian Michael Sanders points out that Harney had a ‘continuing desire to raise the literary standard of Chartist poetic production’ for his working class readers. Harney rejected a lot of poetry submissions as ‘not up to the mark’. His reasoning was that bad poetry couldn’t express good politics: ‘Put simply, Chartists argued that the capacity of the working classes both to recognise and produce good poetry demonstrated their fitness for the franchise.’ Clearly, Harney regarded Walt Whitman’s ‘Resurgemus’ as exemplary.

Whitman’s sympathy for the revolutionary underdogs taking on the European despots was solidified when, in 1848, he moved from Brooklyn to New Orleans to edit the Crescent newspaper. There was considerable interest in the city in the politics of France, and Whitman took a deep interest in the French Revolution of February 1848 which began with the overthrow of King Louis Phillipe, and spread throughout Europe, overthrowing the despotic monarchies of Austria, Italy, and various German states. By 1850, when Whitman returned to Brooklyn, the European Revolutions had been defeated. His poem, ‘Resurgemus’, memorialises ‘That brief, tight, glorious grip upon the throats of kings.’ The poem represents an artistic breakthrough, deploying nature imagery that linked, as Jennifer Stein puts it, ‘the replenishing power of nature to the rejuvenation of revolution and liberation.’ It was the only poem from this period which made it into Whitman collection of poems, Leaves of Grass, five years later.

Hegel’s Process Philosophy

‘Resurgemus’ fitted in well with the ‘editorial environment’ of the Red Republican. The paper was regarded as ‘dangerous’ by the leading ‘opinion formers’ of the day, such as Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle and the Times. Red Republican contributors like Marx, Engels and Macfarlane were steeped in the radical ideas of German philosophy. Whitman had no knowledge of German language, but he appears to have picked up some basics of German philosophy and a feel for dialectical thought from books and articles he read.

Whitman read (exactly when is uncertain) Joseph Gostwick's book of 1854, German Literature. This introduced the philosophies of Kant, Fichte, Schlegel, Schelling and Hegel. Another source for Whitman’s philosophical development was Frederic H. Hedge's The Prose Writers of Germany, which surveyed German thought from Luther and Boehme to Hegel and Heine (again, it’s not known precisely when Whitman read it). In any case Whitman related to these ideas not as a philosopher but as a poet who thought with his instinct and intuition:

‘Space and Time! Now I know it is true, what I guess'd at,

What I guess'd at when I loaf'd on the grass,

What I guess'd while I lay alone in my bed,

And again as I walk'd the beach under the paling stars’ (‘Song of Myself’)

What were these ideas? Whitman's universe, like Hegel's, was not determined from some God-like presence beyond space and time, but was in an endless process of becoming. In Hegel’s philosophy of history the process involves the Idea of Freedom working itself out through contradictions. In Whitman’s words:

‘Victory, union, faith, identity, time,

The indissoluble compacts, riches, mystery,

Eternal progress, the kosmos, and the modern reports.

This then is life,

Here is what has come to the surface after so manythroes and convulsions.’ (‘Starting from Paumanok’)

Wars, revolutions and class conflict drive this process forward. Hegel provocatively argues that it is more meaningful to say that humans are naturally ‘evil’ than naturally ‘good’. In Engels’ interpretation, ‘With Hegel... it is precisely the wicked passions of man – greed and lust for power – which, since the emergence of class antagonisms, serve as levers of historical development...’ For Hegel, the ‘Cunning of Reason’ ensures that the particular purposes of the individual are made to serve the true Substance: the will of the ‘World Spirit’. Once the objective of the ‘World Historical Individuals’ is attained they ‘fall off like empty hulls from the kernel. They die early like Alexander, they are murdered like Caesar, transported to Saint Helena like Napoleon.’

RESURGEMUS

(As published in the New York Tribune 21 June 1850. Reprinted in the Red Republican 3 August 1850)

SUDDENLY, out of its state and drowsy air, the

air of slaves,

Like lightning Europe le'pt forth,

Sombre, superb and terrible,

As Ahimoth, brother of Death.

God, 'twas delicious!

That brief, tight, glorious grip

Upon the throats of kings.

You liars paid to defile the People,

Mark you now:

Not for numberless agonies, murders, lusts,

For court thieving in its manifold mean forms,

Worming from his simplicity the poor man's wages;

For many a promise sworn by royal lips

And broken, and laughed at in the breaking;

Then, in their power, not for all these,

Did a blow fall in personal revenge,

Or a hair draggle in blood:

The People scorned the ferocity of kings.

But the sweetness of mercy brewed bitter de-

struction,

And frightened rulers come back:

Each comes in state, with his train,

Hangman, priest, and tax-gatherer,

Soldier, lawyer, and sycophant;

An appalling procession of locusts,

And the king struts grandly again.

Yet behind all, lo, a Shape

Vague as the night, draped interminably,

Head, front and form, in scarlet folds;

Whose face and eyes none may see,

Out of its robes only this,

The red robes, lifted by the arm,

One finger pointed high over the top,

Like the head of a snake appears.

Meanwhile, corpses lie in new-made graves,

Bloody corpses of young men;

The rope of the gibbet hangs heavily,

The bullets of tyrants are flying,

The creatures of power laugh aloud:

And all these things bear fruits, and they are good.

Those corpses of young men,

Those martyrs that hang from the gibbets,

Those hearts pierced by the grey lead,

Cold and motionless as they seem,

Live elsewhere with undying vitality;

They live in other young men, O, kings,

They live in brothers, again ready to defy you;

They were purified by death,

They were taught and exalted.

Not a grave of those slaughtered ones,

But is growing its seed of freedom,

In its turn to bear seed,

Which the winds shall carry afar and resow,

And the rain nourish.

Not a disembodied spirit

Can the weapon of tyrants let loose,

But it shall stalk invisibly over the earth,

Whispering, counseling, cautioning.

Liberty, let others despair of thee,

But I will never despair of thee:

Is the house shut? Is the master away?

Nevertheless, be ready, be not weary of watching,

He will surely return; his messengers come anon.

WALTER WHITMAN

Leaves of Grass

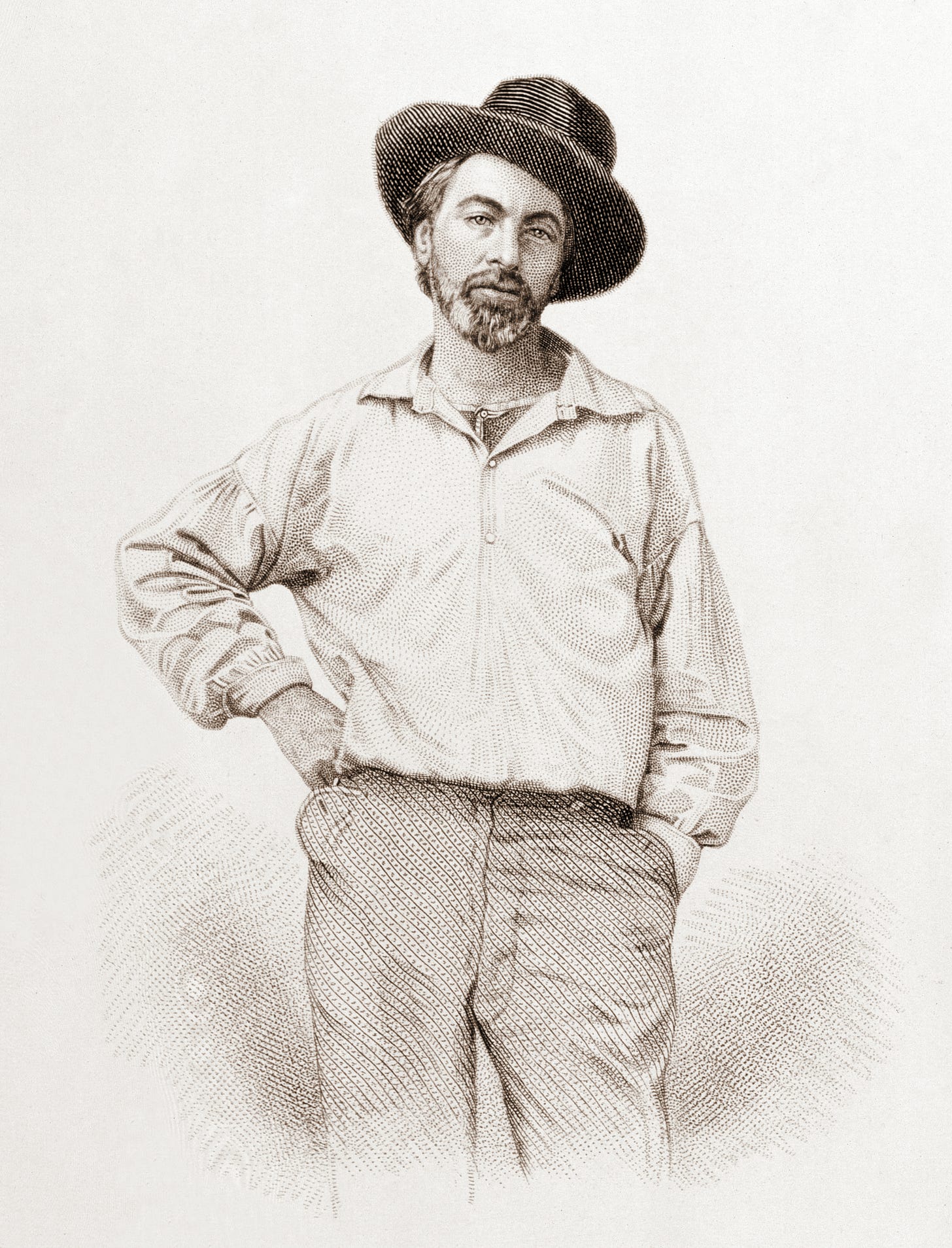

Walt Whitman self-published his first volume of poems on 4 July 1855. The title, Leaves of Grass, was a pun, which in publishing lingo literally meant ‘pages of inferior publications’. None of the twelve poems had titles.Neither the names of the author or publisher (Whitman in both cases) appeared in the volume, although he added an engraving of himself, so as to let the secret out amongst the New England literati. He also included a ten-page preface on poetic and political principles which addressed issues raised by Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay of 1844, The Poet. Emerson, the sage of New England Transcendentalism, expressed the need for a new and true American poet. Whitman said later of Emerson's influence, ‘I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil.’

Whitman’s book was self-advertised as an ‘oddity.’ There was no hiding what would nowadays be called ‘explicit sexual imagery’ and ‘extremist political slant'; nor the fact that the poems broke new ground in abandoning strict rhyme and meter.

Flouting the rules of literary decorum, Whitman reviewed the book himself anonymously in three publications. A piece in the United States Review (5 September 1855) begins:

‘An American bard at last!... We shall cease shamming and be what we really are. We shall start an athletic and defiant literature. We realize now how it is, and what was most lacking. The interior American republic shall also be declared free and independent.’

Initially, Leaves of Grass did not sell well. But Whitman had a marketing ace up his sleeve. He sent a copy hot off the press to Ralph Waldo Emerson, who he had yet to meet. Emerson, to Whitman’s delight, responded in private letter, calling the book ‘the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed’, and greeting the author ‘at the beginning of a great career’.

Without asking Emerson’s permission, Whitman immediately leaked his letter to the press, which amplified the controversy about Whitman’s literary worth. The Transcendentalist supporters of Emerson weighed in, praisinge both Emerson and Whitman. As abolitionists, proto-environmentalists, self-sufficiency advocates, steeped in Unitarianism and German Idealism, the Transcendentalists saw in Whitman a kindred radical spirit. The publicity and controversy created the market for a new edition of Leaves of Grass, expanded and featuring Emerson’s ‘blurb’.

Reception in Britain - ‘an American rough’

By the time Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass found its way to a British readership in 1855-56, Harney’s Red Republican was no more and Chartism was all but dead. Harney had moved to the Channel Islands to edit the Jersey Independent, Marx had become a correspondent for the New York Tribune, Engels was managing his father’s engineering firm in Manchester, and Helen Macfarlane had married and emigrated to Natal.

Strictly speaking there was no British edition of Leaves of Grass in1856. Copies of the second American edition were imported by British publishers, who stamped or pasted the name of their own firm onto the American publisher's title page, or had the imported copies re-bounded with their own impress. The books reception was a minor sensation, though not always in a good way. The Edinburgh News and Literary Chronicle (6 October 1855) reported briefly:

‘A new spasmodic poet has turned up in America. He calls himself Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs,"a Kosmos”. We do not know which to admire most, the matter or the method, both of which are extremely novel.’

The review featured published extracts of three poems from Leaves of Grass, under the titles, ‘The Mashed Fireman’, ‘An Apostrophe to Life’, and ‘A Slave at Auction’.

Other periodicals were not so impressed. The North British Daily Mail (25 April 1856) pronounced in a short piece which was widely syndicated:

‘An American rough, whose name is Walt Whitman and who calls himself “Kosmos”, has been publishing a mad book under the title “Leaves of Grass”...The fields of American literature want weeding dreadfully.”

The London Examiner (22 March 1856) was more thoughtful, but disapproving nonetheless:

‘We must be just to Mr Whitman in allowing that he has one positive merit. His verse has a purpose. He desires to assert the pleasure that a man has in himself, his body... mind and its sympathies. He asserts man’s right to express in himself his delight in animal enjoyment, and the harmony in which he should stand, body and soul, with fellow men and the whole universe... Perhaps it might have been done, however, without always being so purposely obscene and intentionally foul-mouthed, as Mr Whitman is.’

The hostility recalls the denunciations of Harney’s late Red Republican a few years earlier. Charles Dickens. in Household Words. declared that it was his paper’s aim to ‘displace’ the ‘Bastards of the Mountain, bedraggled fringe on the Red Cap, Panders to the basest passions of the lowest natures – whose existence is a national reproach.’

A Times leader of 2 September 1851, entitled ‘Literature For The Poor’, warns that Harney’s content, especially the serialised Communist Manifesto, might have an alarming appeal to those people in the lower orders who form a sort of secret society:

‘… only now and then when some startling fact is btought before us do we entertain even the suspicion that there is a society close to our own, and with which we are in the habits of daily intercourse, of which we are as completely ignorant as if it dwelt in another land, of another language in which we never conversed, which in fact we never saw’.

Walt Whitman, like Karl Marx, spoke ‘another language’ befitting the struggle for new way of life. That language and the ideas expressed are still with us and speaking to power.