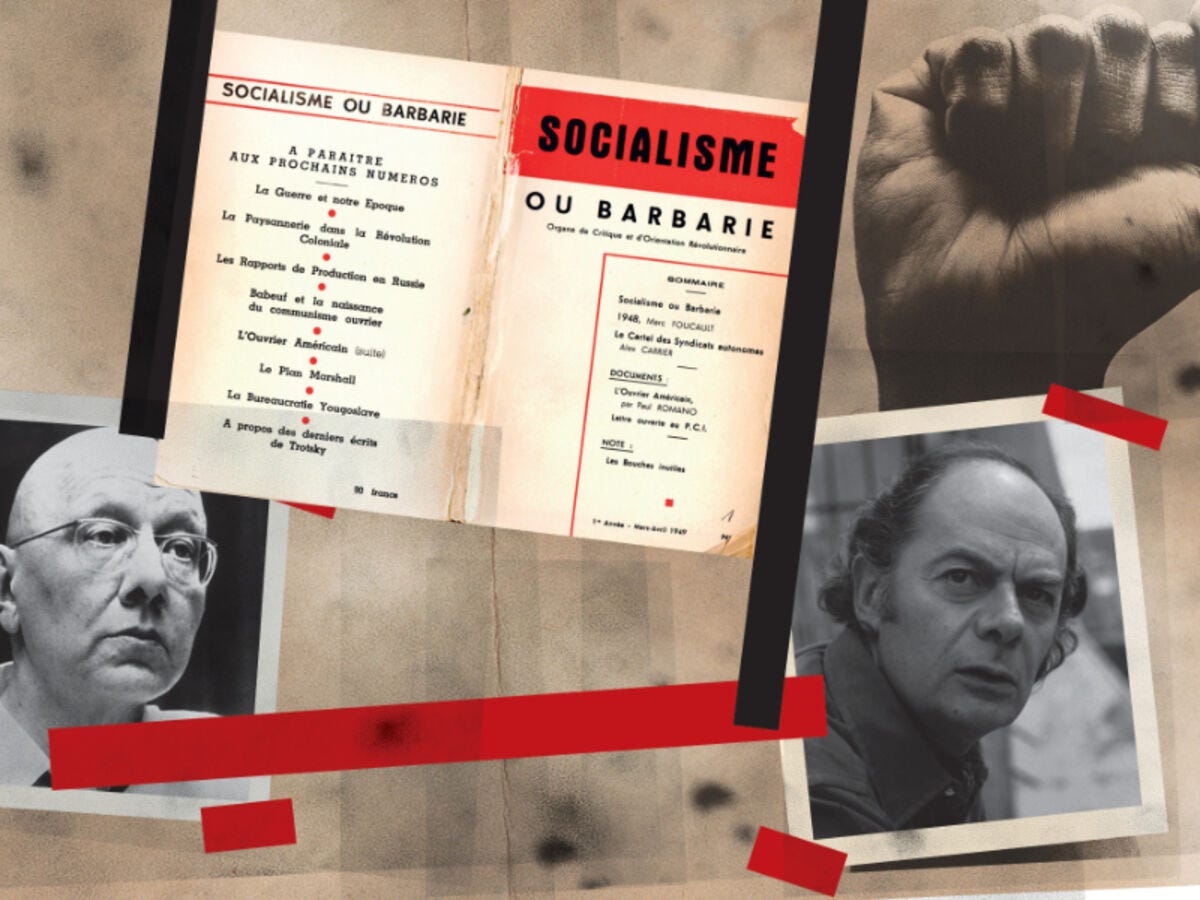

In 1960 Guy Debord joined Socialisme ou Barbarie, while retaining membership of the Situationist International, and remained a member for one year.[i]

Debord argued that the academic specialists had abandoned the “critical truth” of their disciplines to preserve their ideological function. And as, he believed, “real people” were going to come together to challenge the capitalist order, all “real researches” were “converging toward a totality.”[ii] These “real researches” could be found in “militant publications like Socialisme ou Barbarie in Paris and Correspondence in Detroit,” both of which had broken with Trotskyist vanguardism. Both groups had published “well-documented articles on workers’ continued resistance” to “the whole organization of work” and to their depoliticization and disaffection from unions which had become “a mechanism for integrating workers into the society as a supplementary weapon in the economic arsenal of bureaucratized capitalism.”[iii]

Socialisme ou Barbarie, published from 1949 to 1965, was founded by Cornelius Castoriadis and Claude Lefort. Correspondence, published from 1951 to 1962. In 1958, Castoriadis, using the pseudonym, “Pierre Chaulieu,” contributed to the book, Facing Reality, alongside James and Grace Lee Boggs.[iv]

Castoriadis (1922-97) analyzed the implications for radical politics of developments in post-War capitalism. The “crisis” and “immiseration” predicted by “traditional” Marxism now appeared to have been forestalled. With full unemployment and an increasingly affluent workforce, Castoriadis saw the remaining contradictions of the system as the “alienation” of the worker from work and the division between management and the managed (significantly Castoriadis did not, as did Marx, conceptualize the division as between mental and manual labor).

Since Socialisme ou Barbarie believed that workers’ councils would be the organs for transition to a socialist society, there was a reassessment of the earlier “council communism” which had appeared during the German Revolution of 1918-19 and its aftermath. In 1952, the veteran Dutch council communist and astronomer, Anton Pannekoek (1873-1960), wrote to Castoriadis on the issue of workers’ councils and the “revolutionary party”: “While you limit the activity of these councils to the organization of work in the factories after the seizure of power by the workers, we consider them equally as being the means by which the workers will conquer this power.”[v]

Whereas Pannekoek held that the workers would decide for themselves on the organization of the new society once the power of the workers’ councils had been established, Castoriadis had drawn up a veritable blueprint for a new “system” of workers’ councils, with elections at the shop-floor level for a government of councils and a central assembly which would oversee a “planning factory” for coordinating and managing the economy at the national level.[vi]

This looked to Pannakoek like the party-building he was sceptical of. Pannekoek argued that for councilists to retain even the concept of a party – even a non-vanguardist party – was a “knotty contradiction.” Castoriadis, for his part, did not see the role of the revolutionary organization as constituting an external leadership to the working class. He believed revolutionary organization would be necessary to thwart the efforts of “Leninist” parties to “take-over” the autonomous bodies that would be set up by the workers. Castoriadis saw Socialisme ou Barbarie as building the revolutionary organization of the “avant-garde” minority of workers and intellectuals, whose role in the short term would be to protect the immediate interests of the workers. Although this organization would have to be “universal, minority, selective and centralized” -to such an extent that it could be perceived as Leninist - he believed that it could avoid degeneration into a bureaucracy because it would not repeat the fundamental division of management and managed, which the vanguard parties reflected in their theory and practice. The journal carried reports from workers describing the monotony and alienation they felt in their jobs, frequently expressing the view that they, the workers, could self-manage their workplaces much more efficiently and creatively than the existing managers.[vii]

The advent of the Hungarian workers’ councils in the Revolution of 1956 was seen by Castoriadis as an epoch-making anti-capitalist development. Mistakenly, however, he saw Soviet “bureaucratic state-capitalism,” with its highly integrated and centralized bureaucracy, as the “highest” stage of capitalism, and therefore ahead of its Western rivals in the domination of labor by capital – not to mention its ideological hold over workers’ organizations in the West. This position implied that successful revolution might be even more likely in the West, because of the contested democratic space that still existed in bourgeois democracies.

However, the events in Hungary did not develop the revolutionary tendencies of the French working class; rather they just eroded the authority and hegemony of the French Communist Party. The vote in the referendum of 1958 for De Gaulle’s Fifth Republic – ninety per cent in favor – shattered Castoriadis’ faith in the working class as a revolutionary force and led to a significant shift in Socialisme ou Barbarie towards covering struggles against alienation in the “superstructure” – especially in culture and education.[viii] But for the moment, the “industrial” work continued. In 1959 the journal Pouvoir Ouvrier was founded by Socialisme ou Barbarie to propagate the program for workers' self-management based on the theories of Castoriadis, as well as to publish reports from workers on the shop floor. But the “knotty contradiction” of party-and-class identified by Pannekoek soon manifested itself. Claude Lefort (1924-2010) broke from the group in 1958 over what he saw as “a permanent contradiction between the theoretical character of the journal and its propagandistic claims.” In Lefort’s view, which was shared by Henri Simon (born 1922), Castoriadis’ position concealed a “radical fiction” posing as a conception of non-bureaucratic socialism, which in turn concealed both a “communitarian” desire for homogeneity and the inevitability of articulation by a small circle of intellectuals.[ix]

Another issue was raised by Raya Dunayevskaya in 1955. She admired the input of reports by workers in the journal:

“Heretofore socialists and other radicals have been content with publishing a paper ‘for’ workers rather than by them. The fact that some now pose the latter question, and pose it with the seriousness characteristic of the theoretical journal, is a beginning.”

She added however, that to say, “A workers’ paper, yes, but in that case it must come from the workers themselves, and not from us the theoreticians,” was an evasion of the task at hand: “theoreticians cannot be bystanders to a paper that mirrors the workers’ thoughts and activities as they happen.”[x] In 1961, Eugene Gogol of Dunayevskaya’s News and Letters Committees attended a Socialisme ou Barbarie conference in France as an observer and engaged with Castoriadis in discussion of Marx’s 1844 Philosophic Notebooks, the first English translation of which had been published in Dunayevskaya’s book Marxism and Freedom in 1958 as an appendix. Castoriadis argued that Marx’s 1844 writings had “no bearing on Marxian thought after Marx because they were not published until 1920,” and that their philosophic nature made them irrelevant to the question of alienation in modern production.[xi]

After Debord broke from Castoriadis in 1961, the journal International Situationist warned that Socialisme ou Barbarie ran the risk of “providing an ideological cover for a harmonization of the present production system in the direction of greater efficiency and profitability without at all having called in question the experience of this production or the necessity of this kind of life.”[xii] A few issues later (in 1963), the critique continued:

these groups, rightly opposing the increasingly thorough reification of human labor and its modern corollary, the passive consumption of a leisure activity manipulated by the ruling class, often end up unconsciously harboring a sort of nostalgia for earlier forms of work, for the truly 'human' relationships that were able to flourish in the societies of the past or even during the less developed phases of industrial society. As it happens, this attitude fits in quite well with the system’s efforts to obtain a higher yield from existing production by doing away with both the waste and the inhumanity that characterize modern industry.[xiii]

In Socialisme ou Barbarie’s first manifesto of 1949, Castoriadis had insisted that Marxism was “beyond question.” But in the course of the 1950s he developed the view that Marxism was the ideology of an earlier, “market” and “production” stage of capitalism, and that in the modern bureaucratic world, Marx’s Capital, for the most part, was no longer relevant. Castoriadis argued that, with the aid of the state, continual expansion of capitalism could take place unimpeded. In the age of state-capitalism and bureaucracy, a new “ideology” was necessary for the new movement towards a system of workers-self management. Castoriadis himself concluded that Marxism was a “pseudo-scientific” “obfuscation” of nineteenth-century class struggles, which had themselves “allowed the system to function and survive.”[xiv]

By the late 1960s the Situationists were attacking what they saw as Castoriadis’ “unmistakable progress towards revolutionary nothingness, his swallowing of every kind of academic fashion and his ending up becoming indistinguishable from any ordinary sociologist.”[xv]

[i] Vincent Kaufman, Guy Debord: Revolution in the Service of Poetry (University of Minnesota Press: 2006) p. 171.

[ii] Debord, “Perspectives for Conscious Alterations in Everyday Life,” International Situationist, No. 6, S.I. Anthology, pp. 68-74.

[iii] “The Bad Days Will End” (editorial), International Situationist, No. 7. S.I. Anthology, p. 82.

[iv] C.L.R. James, Grace C. Lee, and Pierre Chaulieu (Cornelius Castoriadis), Facing Reality: The New Society, Where to Look for It, How to Bring it Closer (Detroit: Bewick, 1974), pp. 34-39; Cornelius Castoriadis, “C.L.R. James and the Fate of Marxism,” in C.L.R. James, His Intellectual Legacies, eds. S.R. Cudjoe and W.E. Cain (Massachusetts University Press: 1995), pp. 277-97. After 1958 there was no further contact between Castoriadis and James. According to Cudjoe and Cain, Castoriadis was angered because “James published ‘Facing Reality’ without fully working out the ideas contained in the pamphlet and without having Castoriadis’ final approval to publish his section in the pamphlet.”

[v] Pannekoek, Anton. “Discussion sur le probleme du parti révolutionnaire,” Socialisme ou Barbarie, July-August 1952. www.marxists.org/archive/pannekoe/1953/socialisme-ou-barbarisme.htm

[vi] Richard Gombin, The Origins of Modern Leftism (London: Penguin 1975), p. 98; P. Chaulieu, “Sur le contenu du socialisme,” in Socialisme ou Barbarie (July-September 1957).

[vii] Gombin, Origins of Modern Leftism, pp. 99-100; P. Chaulieu [Castoriadis], “Discussion sur le probleme du parti révolutionnaire.” Socialisme ou Barbarie (July-August 1952); P. Chaulieu, “Réponse au camarade Pannekoek,” Socialisme ou Barbarie (April-June 1954).

[viii] Arthur Hirsch , The French Left (Montreal: Black Rose 1982), pp. 108-31.

[ix] Claude Lefort, “Interview.” Telos, No. 30 (1976).

[x] Raya Dunayevskaya, “A Response to Castoriadis’s Socialism or Barbarism” (1955), reprinted in News and Letters, Oct-Nov 2007.

[xi] “Letter from Eugene Gogol,” News and Letters Bulletin, August 1961.

[xii] Debord, “Instructions For Taking Up Arms,” International Situationist, No. 6. S.I. Anthology, p. 64.

[xiii] “Ideologies, Classes and the Domination of Nature,” editorial, International Situationist, No. 8. S.I. Anthology, p. 102.

[xiv] Cornelius Castoriadis, “On the History of the Workers Movement,” Telos, No. 30, 1976.

[xv] “Lire ICO” (editorial), International Situationist, No. 11. S.I. Anthology, p. 372.