This is an extract from the first chapter of 1839: The Chartist Insurrection by David Black and Chris Ford (Unkant, London: 2012)

‘Dear Lord John, I am not in general an alarmist; but I must confess that the present state of the kingdom gives me much uneasiness.’

So began a letter sent to Home Secretary Lord John Russell on Christmas Eve, 1838, from Sir Henry Bunbury, 7th Baronet of Mildenhall. To the manor born in 1778, Sir Henry had served as an army officer in the Anti-Jacobin Wars and risen to the rank of Lieutenant-General. In 1815, he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for War, and personally saw off Napoleon Bonaparte. For when the dethroned Emperor was being held on board a Royal Navy ship moored off Plymouth, it was Bunbury who was sent by the British cabinet to give him the unwelcome news that he was going to be exiled to St Helena.

Bunbury was a staunch Whig. From 1830-32, he held the parliamentary seat for the county of Suffolk. After losing his seat, Bunbury turned his talents to writing military history, for which he was highly acclaimed. But, as a seasoned reformer, he still keenly observed political developments. Parliamentary reformers had nicknamed Home Secretary Russell ‘Finality Jack’ for his statement that since the Reform Act of 1832 the electoral system was as perfect as it ever could be, with 700,000 voters in a country of 25 million. But millions of the disenfranchised were now demanding universal male suffrage, and many of them were – literally – up in arms about it.

Bunbury said that since he had left office he no longer had the means to assess the balance of forces between the government and the ‘disaffected’, but he was now able to view the prospects at his leisure, ‘undisturbed by the hopes or fears or bias of party politicks’. In his estimation ‘a wide-spreading insurrection of the working people’ was ‘far from improbable’, and might result in ‘so much destruction of property, and such a shock to trade and credit and confidence as would be ruinous to this Commonwealth’.

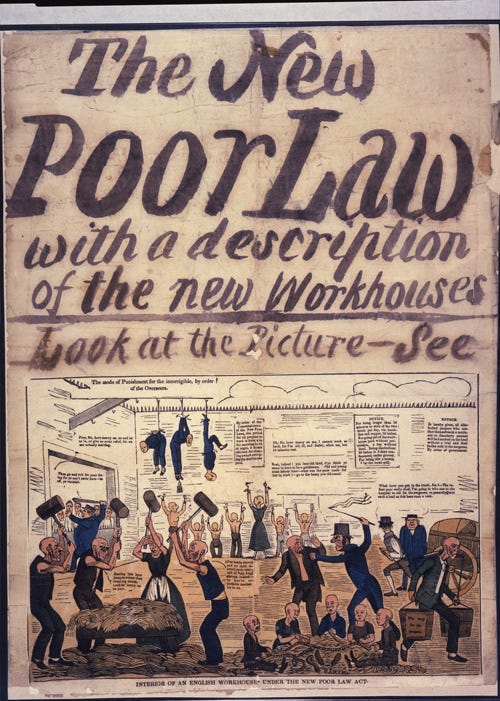

He pointed out that the Whigs’ Parliamentary Reform Act of 1832 had united the propertied classes against the advocates of ‘democratical government’. The extension of the vote to the middle classes had given the propertied classes a ‘vast power’ which was ‘widely diffused and intermingled throughout the country’ and unparalleled anywhere else in the world. But unfortunately, the manufacturing areas were infected with the ‘spreading notion’ that ‘everything is being produced for the rich by the labour of the poor’. The Poor Law Amendment Act had abolished the old obligation of parishes to look after the unemployed during times of distress and established the hated workhouse system. In the North and Midlands there was fierce resistance to the new law: workhouses were being been attacked and burned; and the Poor Law commissioners sent to implement the Act had been subjected to hostile demonstrations and intimidation.

The dangers were not confined to the manufacturing areas, for in general, Sir Henry pronounced, the ‘mass’ was ‘rotten’. In rural areas in the south of England there had been serious disturbances. Farmers in disturbed areas were too ‘selfish and timid’ to unite and stand up to their labourers; and the gentry were ‘helpless’ and inclined ‘to flock with an esprit moutonnier behind the hurdles which they expect the State to interpose between them and the wolf’. He had seen how Justices of the Peace allowed ‘two or three hundred men, women and boys to bully half a county’ and waited on the orders of an absentee Lord Lieutenant to call in the troops. It was essential, he argued, that regular soldiers should be used only ‘for the purpose of holding central points in districts’ and not be ‘frittered away in garrisoning every rich man’s well-furnished mansion’. He feared that troops billeted in the distressed manufacturing districts might be vulnerable to the arguments of the radicals. Therefore the government needed to establish local armed militias which, he stressed, should consist not of ‘hot-headed Tories’ who might endanger the peace but of enlightened men of the gentry and middle classes, even ‘radicals’. Many of these latter, he was certain, ‘would be found amongst the most forward to maintain the cause of law and good order’.

In Sir Henry Bunbury’s former constituency of Suffolk, it was reported by the Ipswich Journal that at a lerge meeting of the Ipswich Working Men’s Association the speakers felt free to ‘blurt out their venom at those who have amassed property and call them knaves and plunderers of the working classes’. The newspaper alleged that the Chartists had as a ‘covert object’ a ‘general confiscation of property, to be effected under the pretext of securing equal political rights, or in other words: to bring all men to the same level’.

What had galvanised the working class radicals was the launch of the People’s Charter which called for universal male suffrage, equalisation of constituencies according to population, abolition of property qualifications for MPs, payment of MPs, annual parliaments and the secret ballot. In July 1838, the Birmingham Political Union and the London Working Men's Association issued a joint call for a National Convention of elected delegates to meet in early 1839, in order to co-ordinate agitation for petition for universal male suffrage for presentation to Parliament. The leaders of the BPU and LWMA were moderate reformers, but the rank-and-file forces they were mobilising contained more militant elements, influenced by the democratic radicalism of Thomas Paine, the socialism of Robert Owen, and the French-inspired left Jacobinism of Buonarroti and Bebeuf. In Suffolk, as elsewhere, the Working Men’s Association was taking the Chartist petition to the agricultural labourers of the county and organising them.

In November 1838, 40 miles east of Bunbury’s manor at Norwich, the young Jacobin-Socialist, George Julian Harney was elected as as a Convention candidate at a mass meeting of weavers and mechanics, estimated at 10,000-strong. Also elected was the Reverend J.R. Stephens, leader of the campaign in Lancashire against the New Poor Law. Stephens wasn’t a Chartist. He was both a Tory - in the sense that he wanted to go back to the paternalist and Christian values of old Rural England - and a revolutionary because he was convinced that the factory system – run by men he regarded as blasphemous murderers and swindlers - would have to be uprooted as thoroughly as Sodom and Gomorrah. In his speech to the Norwich crowd the Reverend declared: “England stands on a mine – a volcano is beneath her.” There was only one way to oppose the New Poor Law, he said:

‘If the New Poor Law comes your way then, Men of Norwich, fight with your swords, fight with pistols and daggers. Women fight with your nails and your teeth, if nothing else will do and wives and brothers and sisters will war to the knife. So help me God.’

Harney’s speech did not match the demagogic power of the preacher’s but he made a good impression, pointing out that in June 1792, 30,000 Frenchmen had petitioned armed with pikes and muskets and that their actions had inspired the rising of the masses two months later. The scenario he had in mind was clear and simple: demand democracy, arm and prepare to seize power when the demands were rejected: ‘We have petitioned too long… Will we have the Charter or die in the attempt to obtain it?’.

George Julian Harney was born to working-class parents in Deptford in 1817. At the age of nine he was taken by his father to see a parade for the Reform candidate in the Southwark parliamentary election. A banner carried in the procession by anti-slavery campaigners showed the figure of a black man in chains with his hands clasped, and bore the inscription ‘Am I not a Man, and a Brother?’ Harney later recalled, ‘there needed not the speeches of a Wilberforce or Clarkson, or the writings of Granville Sharp, to make me an Abolitionist forthwith’. As his father had served as a Royal Navy rigger, George Julian was able to enter the Greenwich School for training with the merchant navy. In 1831 he was taken on as a cabin boy, but he had been just six months at sea when his ship, en route from Lisbon to London, was hailed by an outward-bound vessel and told that the House of Lords had thrown out the parliamentary Reform Bill. On arriving home, Harney found the country plunged into political turmoil that he found more interesting than life at sea.

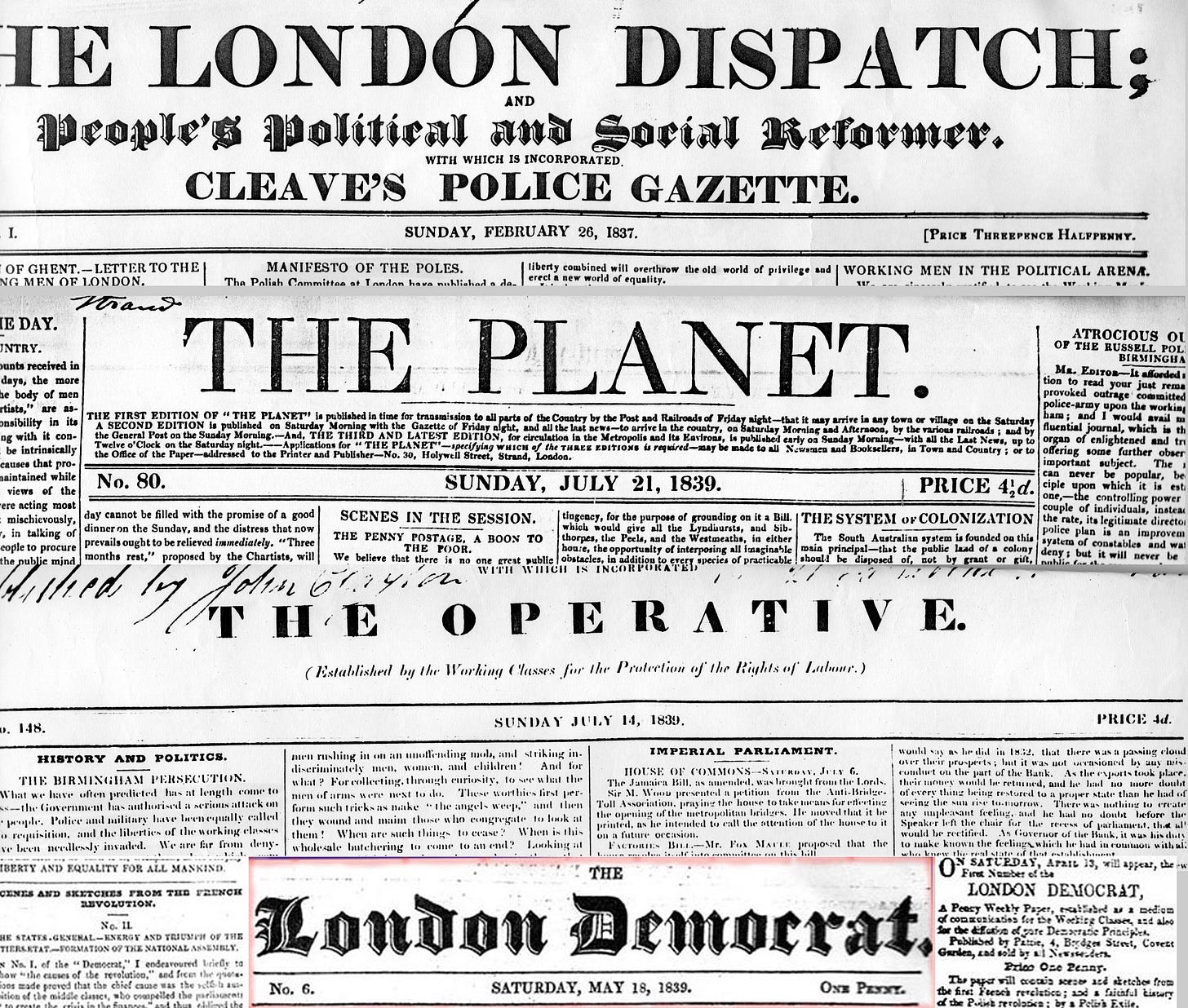

Harney entered the world of radicalism when he became a ‘runner’ for the Poor Man’s Guardian. This paper, which was owned by Henry Hetherington and edited by Bronterre O’Brien, was published from 1833 to 1835, with a weekly circulation that reached a peak of 22,000. It was one of hundreds of illegal publications that came and went between 1830 and 1836 – illegal because they refused to pay the threepenny Stamp Tax that was levied on periodicals carrying news reports. Brought in by a previous Tory administration, this was in effect a tax on knowledge, which made news too expensive for working people.

Radical publishers employed an army of sellers and distributors who used every ruse available to evade the watchful stamp officers: papers might be carried over rooftops, or carted through the streets in a funeral hearse, then handed to customers in a shop through a hole in the wall by an invisible vendor. Anyone caught selling a newspaper without the red government stamp could be arrested and fined, or imprisoned for up to six months; Hetherington, who also published the popular Twopenny Despatch, himself served two terms. In 1830–36 probably a thousand publishers, printers, distributors and sellers were imprisoned throughout the country in what became known as the War of the Unstamped.

In 1834 sixteen-year-old Harney was arrested by stamp officers, and served his first London prison term at Coldbath Fields. A second term followed at Borough Compter Prison within less than a year. By 1836 the War of the Unstamped in London was getting too hot for Harney, so he moved to Derby and joined a distribution network of the Political Register, a radical paper founded by the late William Cobbett. Harney was working under a false name, but a stamp officer from London recognised him. Raided in the middle of the night, he was hauled before the Derby magistrates, to whom he declared:

These laws were not made by me or my ancestors, and therefore I am not bound to obey them . . . knowledge should be untaxed. I have already been imprisoned for selling these papers, and am ready to go to prison again, and my place will be supplied by another person devoted to the cause. I defy the government to put down the unstamped . . . I have no goods to be destrained upon and if I had, neither his majesty, or any of his minions should have them.

Harney’s gall got him a stiff six-month sentence, and when he was released from Derby Gaol in August 1836 he fainted from starvation on the highway to London. He resolved, ‘If I ever forgave the scoundrel who caused this misery then might I never be forgiven myself.’

At this point, Feargus O’Connor, an Irish democrat who stood for repeal of the Act of Union rose to prominence. After losing his Irish parliamentary seat, after being disqualified on a technicality, he turned to agitation in the north of England, in alliance with Anti-Poor Law campaigners. For O’Connor, to ‘agitate with the radicals of England’ was precisely what the Irish Repealers needed to do – for the benefit of both. In 1837 O’Connor launched the weekly Northern Star newspaper, published in Leeds. Despite paying the Stamp Tax and having to sell for a hefty 4½d, the paper was a huge success. By January 1838 the circulation was heading for 20,000 and in 1839 it would average 36,000, with peaks of 50,000. The actual readership was much more, because it became the custom for subscribers to pass the paper around their neighbourhoods, where it could be read aloud in taverns and meeting halls for the enlightenment of the illiterate.

In 1837 the London Working Men’s Association, led by William Lovett, sent missionaries to the provinces to encourage workers to found their own associations to collect signatures for the petition. This mission was successful, and Working Men’s Associations sprouted up in various parts of the country. Lovett’s ‘Moral Force’ perspective contrasted with O’Connors’s ‘Physical Force’ advocacy. In Yorkshire O’Connor was building a strong power base in the more militant Radical Associations, which he drew into the Great Northern Political Union, founded for the purpose of ‘uniting together, upon the general principle of justice all those who, though loving peace, are resolved to risk their lives in the attainment of their rights’.

By the end of 1838 there were 608 organisations – Working Men’s Associations, Female Political Unions, Radical Clubs, Political Unions and Democratic Associations et al – collecting signatures for the Petition and the National Rent. Feargus O’Connor, now known as the ‘Lion of Freedom’, told prospective members of the Great Northern Union that they

‘. . . should distinctly understand that in the event of moral force failing to procure those privileges which the Constitution guarantees . . . and should the Constitution be invaded, it is resolved that physical force shall be resorted to, if necessary, in order to secure the equality of the law and the blessings of those institutions, which are the birthright of free men.’

On 10 August 1838 the anniversary of the overthrow of the French monarchy, Harney formed the London Democratic Association (LDA) at the Green Dragon tavern in Fore Street. The LDA membership card bore an inscription from Buonarotti: ‘Let each of us depend only on institutions and laws, and let no human being hold another in subjection.’ The LDA stood for ‘social, Political and Universal Equality’, support for ‘every rational opposition made by working men against the combination and tyranny of capitalists’; and promotion of ‘public instruction and the diffusion of sound political knowledge’. Within months the organisation would claim an estimated 3,000 members. O’Connor promoted Harney and the Democrats in the Northern Star, praising the LDA as ‘extensive and organised beyond our expectations. We never saw a finer set of men, nor yet determined to be free.’

Since the winter nights had set in, the Chartists had been holding night rallies all over the country, marching silently by torchlight to their meeting places. Often they carried pikes, and fired off the occasional musket salute. O’Connor told a meeting in Rochdale that ‘One of those torches is worth a thousand speeches. It speaks a language so intelligible that no one could misunderstand.’ In response to middle-class alarm, Prime Minister Lord Melbourne banned torch-lit processions.

Having been elected as Chartist Convention delegate for Norwich, Harney was also invited by the Northern Political Union to stand for election in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. On 23 December 1838, at the very time Sir Henry Bunbury was writing to Lord John Russell, Harney boarded a stagecoach in London for a 30-hour, 274-mile journey to the North East.

NEXT: 1839 - The Northern Liberators of 'Canny Newcastle'