1839 - The Newport Uprising

'A more lawless set of men than the colliers do not exist . . . It requires some courage to live amongst such a set of savages.’ - Reginald Blewitt, Whig MP for Monmouth

THE STORY SO FAR

In March 1839 intelligence reports indicated widespread arming and drilling by Chartists in the North of England. General Charles Napier, Northern Commander of the Army complained he might not have enough troops to contain potential unrest.

In May, Welsh Chartist leader, Henry Vincent was arrested and imprisoned at Monmouth, charged with making inflammatory speeches.

In late May, the Chartist petition of 1.3 million signatures was submitted to Parliament.

In July the National Convention moved from London to Birmingham, where a ban on street meetings in Birmingham provoked a massive riot.

When Parliament rejected the Chartist petition the Convention moved back to London and voted for a general strike to begin on 12 August, but disagreements persisted about making it effective. A third of the Convention’s 71 delegates were now either in prison or on bail.

In September, the Convention, having failed to organise a general strike, voted to dissolve itself. Some delegates joined a ‘secret council’ to plot insurrection. When Newport Chartist leader John Frost returned to Wales he found the Chartist movement there was rapidly becoming a revolutionary army. The secret council in England, which was galvanising support for ‘physical force’, decided to follow the lead of the Welsh, whatever they chose to do.

In early November the Rising in south Wales began

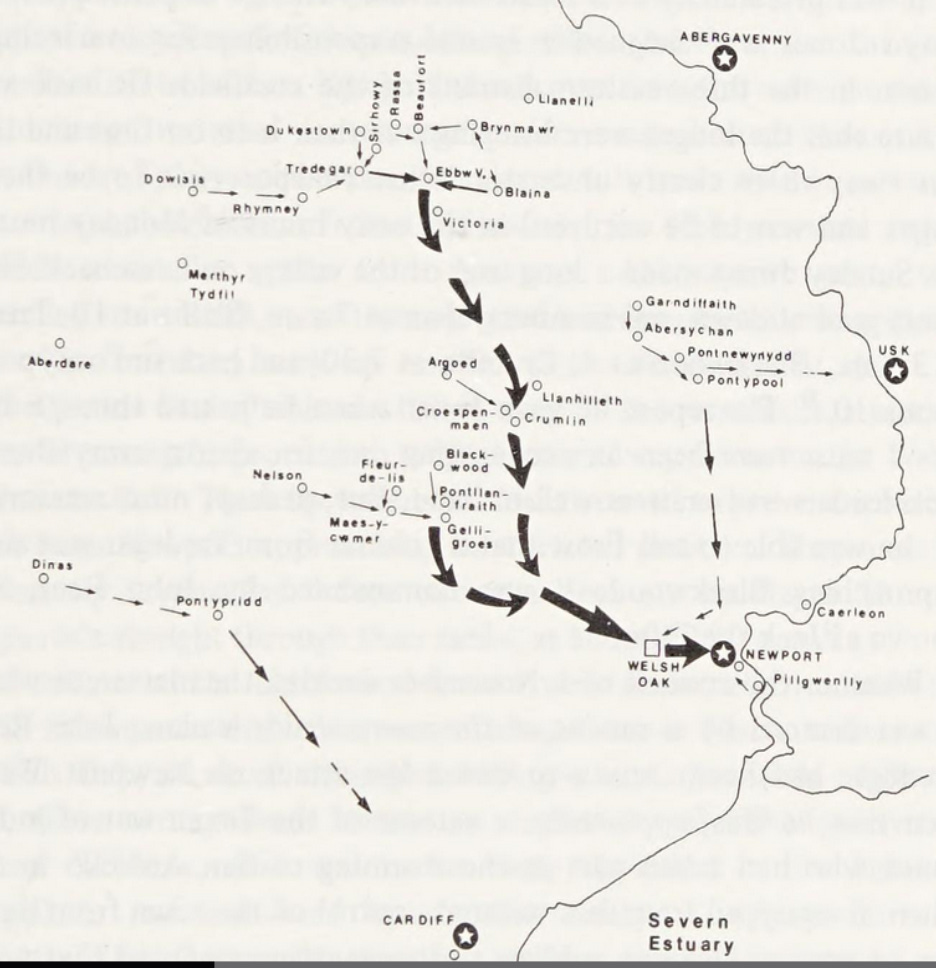

At dawn on Sunday 3 November 1839, William Lloyd Jones mounted his horse and set off from Pontypool on a round trip to Abersychan, Blaenau, Tredegar, Blackwood and Crumlin. His role iwas to muster the three Chartist divisions which were to march on Newport that night: one starting from Pontypool, led by himself; one from Ebbw Vale, led by Zephaniah Williams; and one from Blackwood, led by John Frost.

As Jones proceeded he told the men assembling at local beerhouses to set off at 2 p.m. for Ponypool race-course and in the meantime ‘scour’ for recruits and arms . He told them that posters had been printed in Newport announcing the formation of ‘the executive government of England’, signed by ‘John Frost, President’.

At 11 a.m. at the Royal Oak beerhouse in Blaenau, Zephaniah Williams told the 200 organisers present to go home, collect an extra shirt and some food, then rally the rank and file for a ‘great meeting’ on the mountain at Mynydd Carn-cefn, where they would be joined by contingents from the Heads of the Valleys.

William Lloyd Jones, on reaching Blackwood, met an advance column of armed men from Tredegar, who had travelled south on horse trams. They were led by John Rees, a stone mason and British Army veteran known as ‘Jack the Fifer’. Having been in New Orleans in 1835, when the the Texas War of Independence against Mexico began, he had joined a regiment of volunteers and fought at the Alamo near San Antonio de Bexar. Now back in Wales, he was chosen to lead the assault group at Newport. One of his lieutenants, known as Williams, was a deserter from the 29th Regiment, which had been garrisoned at Newport.

Around 6.30 p.m. Jack the Fifer arrived at Blackwood where, in the middle of a rainstorm, John Frost was gathering the main force. By 7 p.m. the rain showed no sign of letting up, so Frost and Jack the Fifer led the column south along the turnpike path by the side of Sirhowy tramway, so as not to be noticed on the roads. As the brigades proceeded, parties were assigned to scour for more recruits and arms. The main bodies of the march were guarded side and rear, to discourage would-be deserters.

Meanwhile, further north at the Mynydd Carn-cefn mountain, over a thousand men were left standing in the rain until finally, at about 10 p.m., Zephaniah Williams announced they were to march south and meet up with Frost for further orders. Williams told his men that he was sure they would meet no armed resistance. If they did encounter troops, he said vaguely, they should ‘do the best they can’. Williams watched with some satisfaction as the furnaces at the Victoria Ironworks were shut off and then ordered his rain-soddened forces to proceed.

According to the original plan, all of the columns were to meet up at Cefn, on the north-eastern outskirts of Newport. But during the day the rendezvous had been changed to the Welsh Oak beerhouse, a couple of miles to the west. This led to confusion, lack of coordination and delay. The muster at Welsh Oak was spotted by scouts, two of whom nearly ran into the main column and beat a hasty retreat back to Newport to warn Mayor Phillips of the impending invasion.

Phillips had warned Captain Stack, who had seventy troops of the 45th Infantry garrisoned in the Stowe Hill workhouse, to be ready for an attack, and ordered the police superintendent to round up 150 specials for immediate duty. Terrified middle-class refugees were arriving from the valleys, bringing news that others were fleeing in all directions. Phillips sent urgent messages to Bristol and London asking for help, and sent a warning to Monmouth and other towns of the imminent danger. He ordered reinforcements for the constables guarding the Westgate Hotel, and sent a company to guard the bridge over the River Usk.

During the night patrols of specials arrested isolated armed men on the outskirts of Newport, and took them to the Westgate Hotel or to the Stowe Hill workhouse. Captain Stack was told to keep his men at the workhouse out of sight. At daybreak the mayor was told that there were 5,000 Chartists approaching on the outskirts of Newport. Fearing for the safety of the Westgate, he requested that troops be sent there from the workhouse. Thirty-one troops, commanded by Captain Basil Gray, arrived at the Westgate shortly before 8.30 a.m. and stood guard in front of the hotel.

By 7 a.m. Frost could no longer delay, even though he knew that facing the armed force of the state in broad daylight was not what had been planned. The pikemen and musketeers were rallied, and men who had sheltered in barns and cowsheds were ordered to assemble. With Jack the Fifer’s Tredegar column leading from the front, the 5,000 marched to Pye Corner and then along the tramway through Tredegar Park. By this time the rain had stopped and the sun was up.

The column was a mile long by the time it reached the Cwrt-y-bella weighing machine, one mile from the centre of Newport. At this place two boys coming from the town were asked where the soldiers were, and they said some had gone to the Westgate Hotel. Frost decided that the hotel and not the workhouse garrison was the immediate object. At the Waterloo beerhouse, near the bank of the River Usk, Jack the Fifer ordered the marchers to halt. He called for those carrying guns to step forward, and carefully organised the columns of pike-men six abreast, with a gunman at the end of each rank. He then exchanged his pike for the pub owner’s gun, which hung over the fireplace.

Muskets were fired simultaneously to make sure the rain hadn’t dampened the powder and then Jack the Fifer gave the order: ‘March!’. They proceeded to the turnpike gate on Stowe Hill, 200 yards from the workhouse, where there were thirty troops under the command of Captain Richard Stack, and a cache of arms. The Chartist leaders had to resist arguments from the rank and file to attack both the workhouse and the house of magistrate Lewis Edwards, which was nearby. Frost called out, ‘Let us go towards the town, and show ourselves to the town’ – a rather ironic statement, considering that the whole point of the operation had been to take the town under cover of darkness.

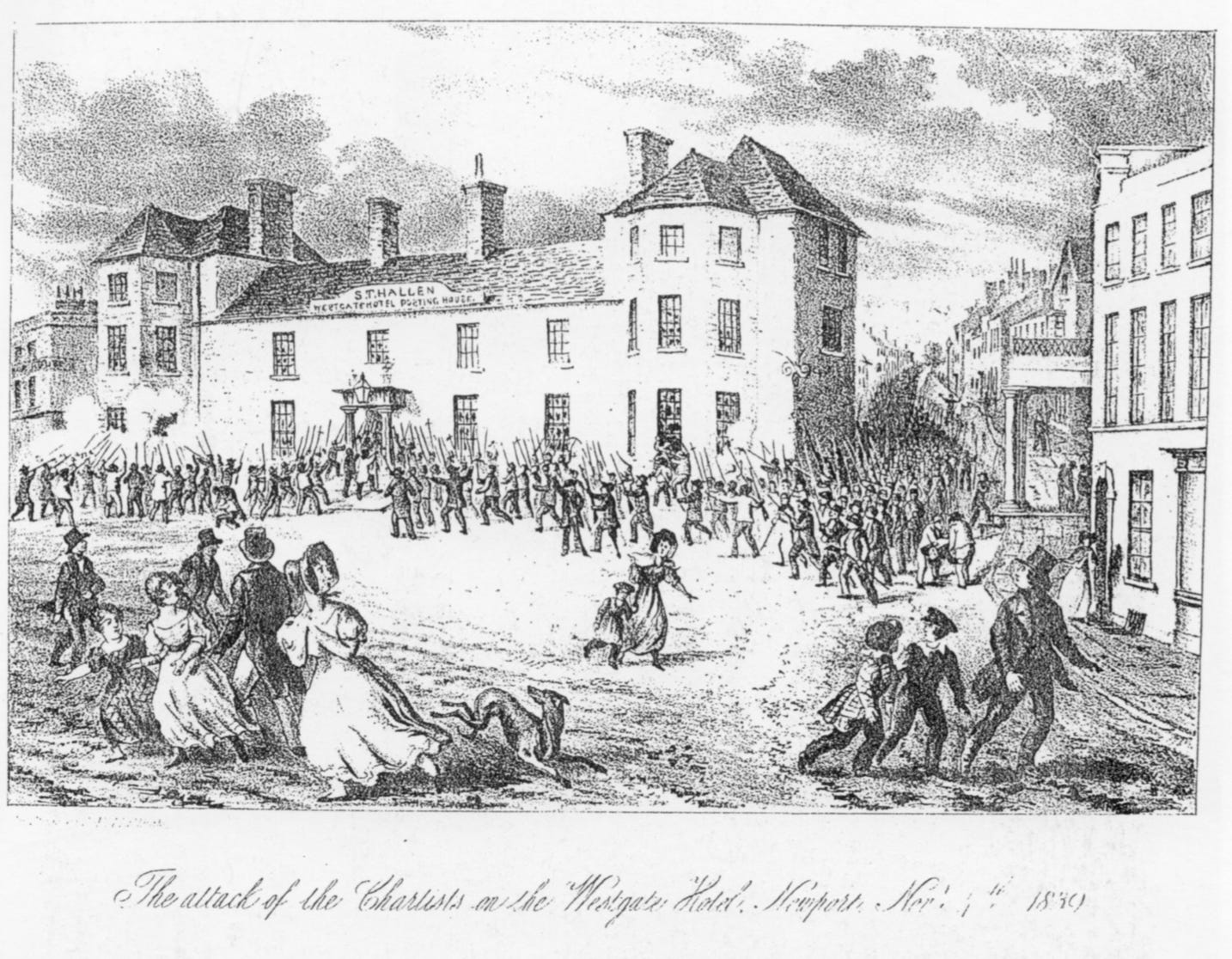

At 9.20 a.m. the marchers came down Stowe Hill, some firing weapons into the air and others shouting. The troops at the front of the Westgate were called into the building, where they were joined by sixty-odd specials. As the noise of the approaching Chartists grew louder, Mayor Phillips ordered the troops in the walled yard at the back of the Westgate to come inside as well.

The developing confrontation was now beyond the control of the three ‘Generals’ of the Rising. Zephaniah Williams was 600 yards away at the top of Stowe Hill, rallying stragglers; William Jones was miles away on the road from Pontypool; and John Frost’s whereabouts were uncertain. Frost was certainly in the close vicinity of the Westgate, but when the shout went up from the men near the front steps, ‘Mr Frost, appearance to the front,’ he was nowhere to be seen.

At the front of the Westgate marchers stormed up the steps, where a scuffle broke out. Each side grabbed at the other’s weapons, and the pikemen stabbed at the shutters of the hotel’s front windows. Jack the Fifer, waving a sword, appeared at the front and someone shouted the order, ‘In my boys!’

A witness, Edward Patton, said, ‘I was distant from the door of the Westgate twenty-five yards . . . I could not say where the firing began. No man could judge. You nor I could not tell. Saw no smoke outside. It is likely enough the firing began from the Westgate inn.’ However, a special constable claimed that as he slammed the door it caught a Chartist gun, which went off. This may have been the first shot.

Captain Gray of the 45th Infantry saw assailants form from column into line, assisted by ‘powder monkeys’ carrying bags of powder and ammunition. According to his testimony, the rush to the door coincided with small-arms fire striking the windows. It was at this point that Gray ordered his men to load their rifles with ball cartridge, while he and Mayor Phillips threw open the shutters to give the soldiers a clear shot at the invaders.

The immediate effect of throwing open the windows was to make those inside more vulnerable to incoming fire. Mayor Thomas Phillips and Sergeants Daily and Armstrong were hit and wounded, as were two of the special constables in the hall. Shots were also fired in the entrance hallway. Some of the specials fled further into the building or up the stairs, while others, including the superintendent, jumped over the back wall and headed for home. Those fleeing may have only survived because the Chartist gunmen could not get a clear shot at them, since there were so many people on the streets.

Gray ordered his soldiers to open fire. The first volley was directed at the crowd in front of the hotel. As the musket balls slammed into the crowd with devastating effect, someone shouted the order ‘Fall off,’ and the crowd ran for cover. Then came a second volley directed at those who could still be seen at the front. The Westgate was also being assaulted from the rear: an armed group had entered the back of the hotel through the yard. Inside, the soldiers, no longer taking fire from the front, opened the door leading to the passage way and rear door, fired a third volley of shots and then fired intermittently. At first the invaders pressed their attack under cover of the gunsmoke, but faltered when they saw the bodies of their comrades and were hit themselves. When the smoke cleared, according to one of the specials, ‘there was a scene, dreadful beyond expression – the groans of the dying – the shrieks of the wounded, the pallid ghostly countenances and the bloodshot eyes of the dead, in addition to the shattered windows, and passages ankle deep in gore’.

By this time there were more than twenty men either dead or mortally wounded. There were five dead in the hotel and four in the street in front of it, with others in the surrounding area. Some of the wounded, who were carried away by comrades, died later.

Jack the Fifer was next seen retreating towards the Waterloo beerhouse and the Cardiff road. As Zephaniah Williams finally approached with his division there were thousands fleeing in the opposite direction. Frost was seen heading through Tredegar Park, broken and sobbing. Later he reportedly said, ‘I was not the man for such an undertaking, for the moment I saw blood I became terrified and fled.’ The attack had become a rout.

Ten minutes after the fighting had started Captain Gray ordered a ceasefire. In the streets surrounding the Westgate 150 weapons were recovered.

The Valleys remained in a state of disturbance for some days afterwards, with middle-class residents still fleeing the area. Within days, troops at Abergavenny, Brecon and Bristol were being reinforced. A troop of the 10th Hussars arrived from Bristol at Newport by steamer, and several companies of infantry marched to Newport from Bristol.

Frost fled Newport through Tredegar Park and headed in the direction of Cardiff. Near Castleton he hid himself inside a coal tram. When he emerged after eight hours the first thing he saw was a bill offering £100 reward for the capture of himself, Zephaniah Williams, William Jones and Jack the Fifer. Frost decided to return to Newport, say farewell to his family and then attempt to flee the country, but he was found and arrested. William Lloyd Jones was caught after a brief struggle at Crumlin. Zephaniah Williams almost escaped into exile: he was caught on the merchant ship Vintage at Cardiff just before it sailed for Portugal. Jack the Fifer, who was reportedly shot through the hand at the Westgate, made it into exile and rejoined the Army of Texas.

Frost had been spoken of by his supporters as the ‘Lord Protector of South Wales’. But unlike Cromwell, he couldn’t conceive of leading a real army because he couldn’t accept the need for real violence. He wrote later: ‘so far from leading the working men of South Wales, it was they who led me, they asked me to go with them, and I was not disposed to throw them aside’.

As George Julian Harney would reflect a few years later in a letter to Friedrich Engels, ‘A popular leader should possess great animal courage, contempt of pain and death, and be not altogether ignorant of arms and military science. No chief or leader that has hitherto appeared in the English movement has these qualifications.’

A hundred and fifty were arrested in South Wales in the weeks following the Rising. Twenty-one of them were indicted for high treason.

[Another extract from 1839: The Chartist Insurrection by David Black and Chris Ford, (with an introduction by John McDonnell M.P.). First published in paperback by Unkant Books in 2012. It has now been re-issued as an Ebook by BPC Publishing. Available from Amazon.]