1839: The Rising of the Women

‘Chartist women’s refusal to let themselves be excluded from the public sphere heightened the threatening aspect of Chartism to the ruling class'

4 February 1839 was the day the royal carriage carried Queen Victoria through the streets for her first opening of Parliament. It was also the day of opening of the Chartist National Convention at the British Coffee House, Cockspur Street.

The Convention began its proceedings at 10 a.m. on 4 February. Robert Lowery, delegate from the North East, recalled:

The British Coffee House being close by, those of us who had never seen Her Majesty made a general rush to see her and her procession. Some of the gentlemen in waiting would have been astounded at the free criticisms and remarks made upon the beefeaters and paraphernalia of the procession.

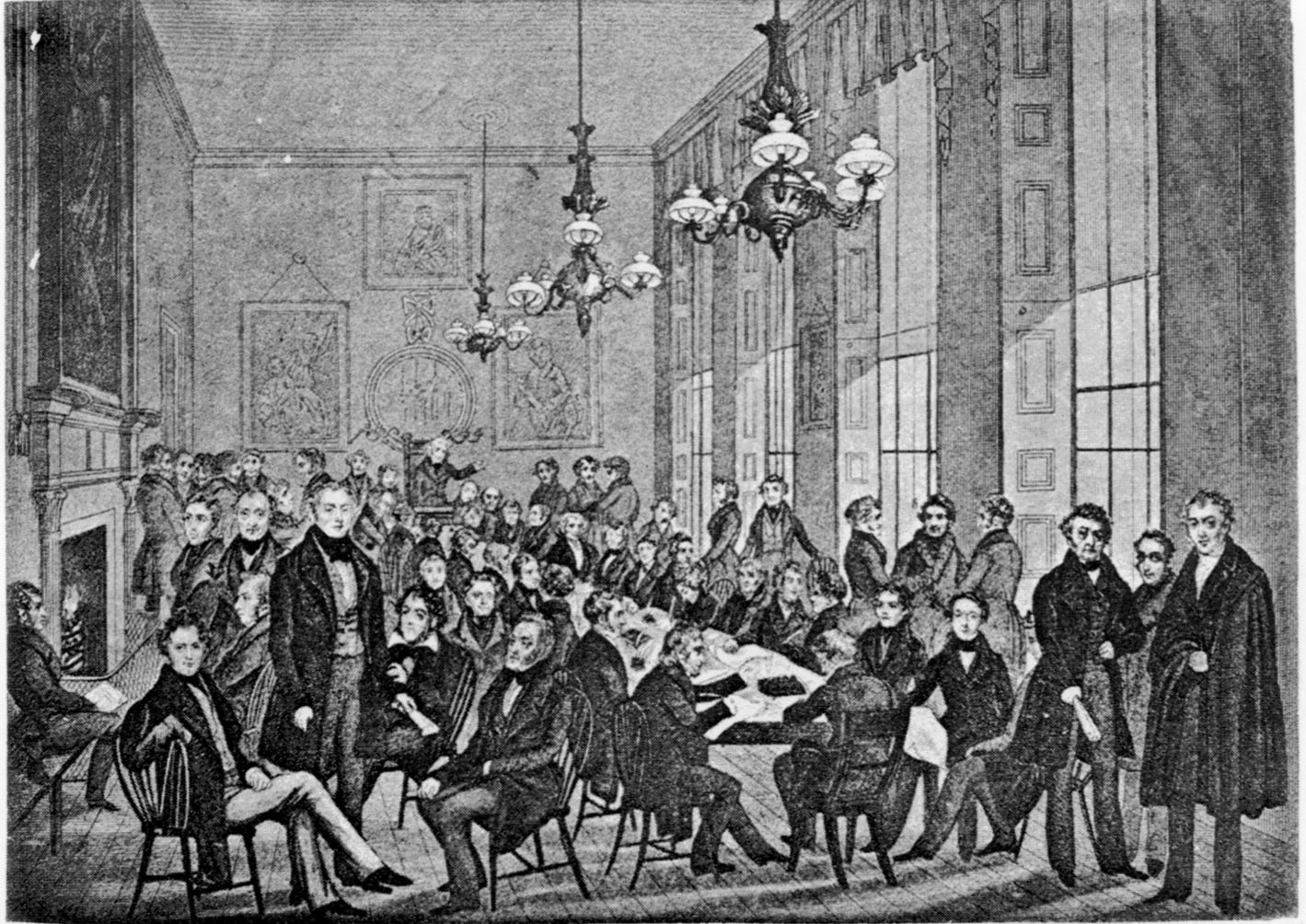

The drawing by an unknown artist of the opening of the National Convention at the British Coffee House shows a large room with paintings, fine drapery and chandeliers. The delegates are smartly dressed and looking statesmanlike and solemn, as if they were preparing to determine the fate of the nation. So far over a half a million signatures had been collected for the petition and almost £1,000 had been raised for the National Rent, to finance the work of the Convention. The Convention met with fifty-three delegates in attendance, all of them men. Out of a total of seventy-one who attended during the Convention’s seven-month existence, forty were working men, fifteen were newspaper editors or publishers, and the rest were small businessmen or professionals in law, church or medicine.

On 6 February, the Convention moved to a cheaper venue at Dr Johnson’s Tavern, Bolt Court, Fleet Street. John Frost of Newport was elected as chairman, a move which led to the Home Office terminating his position as a magistrate weeks later.

The atmosphere of the early Convention is captured in the memoirs of the French feminist, Flora Tristan, who gained admittance to its proceedings accompanied by a female friend close to the Chartist leadership. The two women turned off Fleet Street into a narrow passage leading to a beer house, where they were challenged for the password by a pot-boy sentry. On providing it, they were led through a back parlour into a small courtyard, and along a corridor to the door of the meeting-room. Tristan wrote:

. . . nobody was admitted except after being vouched for by two known members. These wise precautions prevented spies from slipping inside. The first thing that impressed me was the expression on the faces of the delegates . . . each head had a striking individuality of its own. There were about thirty or forty members of the National Convention present and about the same number of young working-class sympathisers. I was pleased to find five French working men and two women of the same class among them. Every one present followed the discussion with alert attention.

On 11 February the Ayrshire tailor Hugh Craig proposed that the Convention urgently needed to make a clear pronouncement on what ulterior means they should recommend to the people, should ‘it unfortunately happen that the delegates fail to convince the members of the House of Commons of the justice of the principles of the People’s Charter’.

Feargus O’Connor dismissed the idea that discussion of ulterior measures would lessen parliamentary support for the petition. He was convinced that popular support for the Convention depended on making it clear that the petition would be their ‘last notice to the House of Capitalists’. If Parliament rejected it, he promised, ‘the Convention would do something, within the law, which would afford a demonstration of the people’s strength and determination’.

As well as the extension of the Chartist campaign into new areas of the country, there was an intensification of efforts within the movement’s existing strongholds which drew in a huge wave of female support. If the huge estimates for attendance at mass meetings in 1838–39 were remotely accurate, then there must have been a great number of women present. Women had already made their presence felt in mobilisations against the New Poor Law as they felt threatened by the state’s new power to destroy families, by separating wives and children from husbands in the new workhouses – which became known as ‘Whig Bastilles’. Although the People’s Charter only called for male universal suffrage, Chartism gave women a number of roles, such as collecting signatures for the petition and money for the families of political prisoners, adorning the banners with striking images and slogans, enforcing ‘exclusive dealing’ with pro-Charter shopkeepers, organising Chartist tea parties, teaching at Chartist Sunday schools and organising public meetings of the new Female Chartist Societies.

There were more than a few male Chartist leaders who praised women’s capacity to absorb ideas as superior to men’s. Robert Lowery, for example, describing his audiences in 1839, ‘found the average mind and manners of the women much superior to the men among the poor. Their powers of thinking and observing had evidently been more exercised’. He found that male attitudes to the need for exclusive dealing were often deficient when compared with their female counterparts: ‘the man that will not go to the length of the street to spend his money in the shop of a friend or a store the profits of which he may be sure, will never walk ten miles with the musket on his shoulder to fight for freedom’.

Feminist historian Jutta Schwarzkopf argues that despite the important mass activity of women which marked the beginning of Chartism, the failure to fight for female suffrage and the circumscribing of women’s ambitions to being ‘good homemakers’, had the effect of holding back the radicalising process for the long term. Certainly, the articles and addresses published by Female Chartist Associations during this period show that the writers had, as Schwarzkopf puts it, ‘absorbed the movement’s political creed’ that the workers were the real producers of wealth, and that the “class legislation” of “aristocratic misrule” should be replaced by democracy. Schwarzkopf says: ‘In the context of general working-class insubordination, Chartist women’s refusal to let themselves be excluded from the public sphere heightened the threatening aspect of Chartism to the ruling classes.’ As the Newcastle Female Chartists declared,

We have been told that the province of woman is her home and that the field of politics is to be left to men; this we deny; the nature of things renders it impossible and the conduct of those who give the advice is at variance with the principles they assert.

Schwarzkopf points out that, although the rebellion of women against their ‘mission’ to stay in the home was welcomed by Chartist men in the organisational sense, they expected women to accept their mission in the ideological sense, though ‘infused with a sense of class consciousness’. The December 1838 address by the Nottingham Female Political Union said: ‘At a time like the present, our energies are required in aid of those measures in which our husbands, fathers, brothers and children are so actively and zealously engaged.’ Schwarzkopf comments: ‘This pose severely hampered women’s political self-expression. It effectively prevented them from establishing themselves as political agents in their own right with needs and aspirations specific to them as women.’ Furthermore,

. . . this pose implied that the women were happy to support a struggle, the primary object of which – universal male suffrage – ostensibly did not affect themselves . . . Common social origin, regardless of gender, was to ensure that working-class women’s grievances would be considered sympathetically. Far from addressing any forms of sexual antagonism, such gender-blind political representation helped remove them from the agenda of class politics.

Although Chartist ‘ideology’ never recognised women’s role as ‘political agents in their own right’ with specific needs and aspirations, Schwarzkopf points out that not all women in this early period towed the line. The Female Chartist Association of Ashton, for example, fully expected female suffrage to follow automatically from the enactment of the Charter. Certainly some Chartist men ‘privately’ agreed with this view. William Lovett later claimed that when he drafted the People’s Charter in 1838 he had included a clause for the extension of the franchise to women, but this was removed in the face of arguments that it would hold up the enfranchisement of men. But as historian Dorothy Thompson has shown, it was after the draft of the Charter was circulated nationally to associations that the proposal to include women’s suffrage was put forward, presumably by groups from the provinces. Lovett, in a second printing of the People’s Charter that same year, took note of the suggestion as a ‘reasonable proposition’, but expressed ‘fears of entertaining it, lest the false estimate man entertains for this half of the human family may cause his ignorance and prejudice to be enlisted to retard the progress of his own freedom’. Since, as Thompson points out, the LWMA did not admit women as members, the ‘fears’ were not surprising. Thompson also points out that whilst the LWMA did not admit women members, the ‘Jacobin’ London Democratic Association under George Julian Harney’s leadership established ‘autonomous’ female organisations. In May 1839 Elizabeth Neesom, of the London Female Democratic Association, said – in a clear ‘feminist’ tone:

[we] consider it our duty to co-operate with our patriotic sisters in the country to obtain the Universal Suffrage in the shortest possible time [and] to annihilate the cruel, unjust and atrocious New Poor Law (miscalled!) Amendment Bill, to support with any means in our power any patriot engaged in the great struggle for freedom who may need our assistance and to destroy for ever this cruel murdering system of transporting our children to the burning sands of Africa or immuring them in the horrid cotton hells and treating them worse, for no other crime than that of being poor. Sisters and friends, we entreat you to shake off that apathy and timidity which too generally prevails among our sex (arising from the prejudices of a false education) . . . To those who may be, or appear to be, surprised that females should be daring enough to interfere with politics, to them we simply say that, as it is a female [Queen Victoria] who assumes to rule this nation in defiance of the universal rights of man and woman, we assert in accordance with the rights of all, and acknowledging the sovereignty of the people our right, as free women (or women determined to be free) to rule ourselves.

The East London Female Patriotic Association, which was affilated to the London Democratic Association, called for a campaign of ‘exclusive dealing’ with ‘friendly’, pro-Chartist shops and businesses, and made it clear that the Association was self-determined as regards which men should be allowed to address it. The Association would consist of ‘females only’ and would let ‘no gentleman be admitted without the invitation of a majority of the members present’.

The Chartists’ failure to support women’s suffrage in 1838 left a legacy that lasted throughout the century. The level and militancy of women’s involvement was not sustained in the movement’s later years. In Schwarzkopf’s view, ‘It could be argued that, after the demise of Chartism [in the 1850s], women dropped out of working-class politics not least because of the movement’s obvious failure – given its inability to arrest the pace of industrialisation – to reinstate them into what was commonly agreed to be their proper position of wives and mothers.’

(NEXT UP: The Newport Rising)

1839: The Chartist Insurrection by David Black and Chris Ford, (with an introduction by John McDonnell M.P.) was first published in paperback by Unkant Books in 2012. It has now been re-issued as an Ebook by BPC Publishing. Available from Amazon.